FREE U.S. SHIPPING ON $65+ ORDERS.

FREE U.S. SHIPPING ON $65+ ORDERS.

Menu title

This section doesn’t currently include any content. Add content to this section using the sidebar.

Your headline

Image caption appears here

$49.00

Add your deal, information or promotional text

*

Historic photo behind song "Jesse Got Trapped in a Coal Mine."[/caption]

Historic photo behind song "Jesse Got Trapped in a Coal Mine."[/caption] Elaine enjoying her new tee.[/caption]

Elaine enjoying her new tee.[/caption]*

*

*

A museum artifact illustrates a surprise turn in Roy Acuff's career.[/caption]

A museum artifact illustrates a surprise turn in Roy Acuff's career.[/caption] Recordings from the Bristol Sessions can be heard and albums are on display.[/caption]

Recordings from the Bristol Sessions can be heard and albums are on display.[/caption]*

*

With so many great towns in Dixie, we couldn’t possibly hit them all. But after much heated debate, we’ve put together a bracket of 32 of the South’s finest. For the record, we kept it to towns, not cities, capping the population at 150,000 (sorry Atlanta, Nashville, and Dallas). There are historic towns such as Charleston and St. Augustine, artsy towns (Athens, Bentonville), college towns (Oxford, Chapel Hill), and just about everything in between.

Greenville, South Carolina. Photo by dustinphillips on Flickr.[/caption]

Greenville, South Carolina. Photo by dustinphillips on Flickr.[/caption]

*

Be it known that I, Micajah Dyer, of Blairsville, in the county of Union and State of Georgia, have invented certain new and useful Improvements in Apparatus for Navigating the Air; and I do declare the following to be a full, clear and exact description of the invention, such as will enable others skilled in the art to which it pertains to make and use it, reference being had to the accompanying drawings, which form part of this specification…

Clark Dyer and his wife Morena, photo courtesy Union County Historical Society.[/caption]

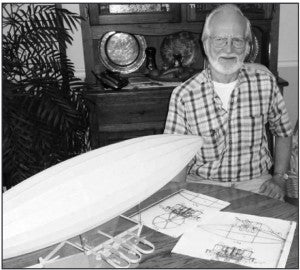

Clark Dyer and his wife Morena, photo courtesy Union County Historical Society.[/caption] Dyer descendant Jack Allen, a retired Delta Airlines mechanic. crafted every piece of Clark Dyer’s airplane model to scale. Photo courtesy of The Towns County Herald.[/caption]

Dyer descendant Jack Allen, a retired Delta Airlines mechanic. crafted every piece of Clark Dyer’s airplane model to scale. Photo courtesy of The Towns County Herald.[/caption] The Center is housed in a renovated courthouse.[/caption]

The Center is housed in a renovated courthouse.[/caption]Iva Williams and Danny McLaughlin don't have much regard for the official records on panthers. You see, officially, the last of these big cats was killed in West Virginia back in 1887, and black panthers, also known as mountain lions or cougars, never, officially, even existed in North America.

That would all be fine and good if seventy-year-old Williams and her son-in-law McLaughlin hadn't seen and heard these giant cats—one of them being pitch black. The two of them live among the 300,000 acres of national forest in Pocahontas County, West Virginia. With miles and miles of unspoiled woodlands, ranging from high peaks to cranberry wilderness, the area could certainly give a wild panther plenty of room to roam, but has it?

Take a listen to Williams and McLaughlin, who paused their old time music jam to talk with their neighbor Roxy Todd about their Kennison Mountain sightings.

Do you think these elusive creatures still roam eastern forests? Has a cougar crossed your path? Or are folks like these just seeing what they want to see?

https://soundcloud.com/traveling219/black-cat-of-pocahontas-county

This story was collected as part of Traveling 219, a project that uses audio stories and the Web to create a modern guide to the scenic stretch along U.S. Route 219 in West Virginia. The project is led by members of Americorps, the national community service corps, with support from Allegheny Mountain Radio, the West Virginia Humanities Council, and Pocahontas County Free Libraries.

*

Guest blogger, Peter Brackney.[/caption]

Guest blogger, Peter Brackney.[/caption] Kentucky weather forecaster. Photo by David Reber on Flickr.[/caption]

Kentucky weather forecaster. Photo by David Reber on Flickr.[/caption]"Local in character, [this film] should arouse more than ordinary interest. But what is such interest compared with that which is certain to be displayed in this same motion picture when shown ten or twenty years from now? Many changes will take place. The progress of science, education, and humanity itself, will have made obsolete much contained in this film." — Introduction to Charleston Beautiful

...and get 10% off your first order!

We use cookies on our website to give you the best shopping experience. By using this site, you agree to its use of cookies.

Plus first dibs on sales, the latest stories, & heaps a'luvin from us.