"Under my basement stairs, there’s a toilet, and that toilet was for the help. They had to go to the bathroom in the basement because white people did not want them using their restroom."

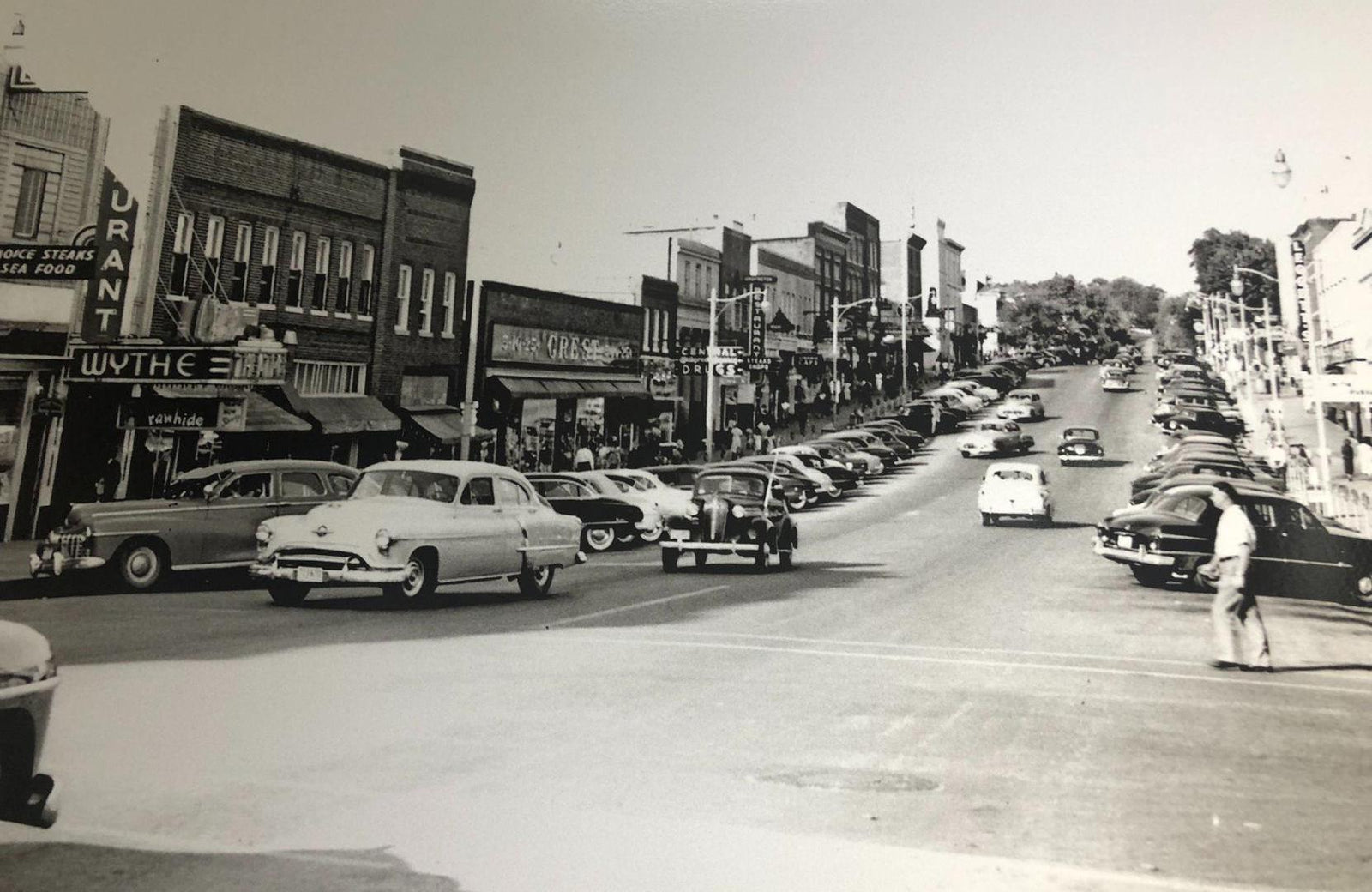

If you've spent time in older Southern homes, there's a good chance you've encountered a toilet like mine. Tucked under the basement stairs of our 1927 foursquare in Roanoke, Virginia, it's where the help used the bathroom, and the help, back then, was almost always Black.

I wince whenever I walk by it, on the way to our basement fridge or getting Christmas decorations. It's a grim reminder of a mean-spirited era, one none of us created but we all inherited. The folks at Practical Preservation podcast recently invited me to talk about how we can face the full histories of our homes — the good stuff and the grim stuff.

"The trend I see in preservation is to acknowledge all the history," Danielle Groshong-Keperling said during our interview. She's the host of this weekly preservationpalooza, which covers everything from old smokehouses to historic gardens. It's been named as a great podcast for historic preservation fans by The National Trust for Historic Preservation.

We also chatted about my family homeplace and tough choices we make to save money during the restoration process. When replacing long-gone steel casement windows, I once replicated the originals using wood rather than steel.

"We took it as close as we could," I said, "without going broke and having to sell our cars!"

If you've ever restored an historic home, we'd love to hear about your trials, joys, and discoveries. Please be sure to leave a comment below.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

A NEW DAY: RESTORING MY FAMILY HOMEPLACE

A ROCKY ROAD TO THE DEARING HOMEPLACE

COUSIN EDNA, AGE 101, SINGS THE TEXAS RANGERS