Bulldozer overgrown with kudzu. Photo by Keithspaulding via dreamstime.

“That feeling of being in the field and eating food while it’s still warm from the sun and the smell of the dirt is still in the air inspired me very early.”

This spring, celebrity chef Sean Brock traveled through Japan’s countryside. Between ten-thousand year-old-villages, he saw a landscape that “felt like home.”

It wasn’t because he has been there often, although he has, but rather because rural Japanese was so similar to his homeland in Southwest Virginia. That’s not entirely surprising. Japan and the Appalachian region are roughly the same size, and they share a latitude, which means some of the same things grow there. (Yes, kudzu, but others, too).

Sean didn’t travel to Japan just for leisurely train rides though. He went to explore the country’s food traditions — some of which are centuries older than the English language — and then take those lessons home.

He shared some of those lessons just a few weeks later in Wise County, Virginia, where he was raised until he was a young teen. His years there, spent cooking and foraging, were among his most formative, and they made his keynote at the eighth annual Southwest Virginia Economic Forum at the University of Virginia’s College at Wise especially meaningful.

While Sean has won multiple James Beard Awards (the Academy Awards of the restaurant business), and his cookbooks have been The New York Times bestsellers, he first wanted to talk about conversations with his Appalachian grandmother, how they were both astounded after his first few days of work in a nice restaurant.

“I remember coming back and telling her, ‘You wouldn’t believe this lettuce they’re making people pay for at this restaurant,’” he told attendees, “Because I grew up eating hers directly from the garden. And that flavor of the field, that feeling of being in the field and eating food while it’s still warm from the sun and the smell of the dirt is still in the air inspired me very early.”

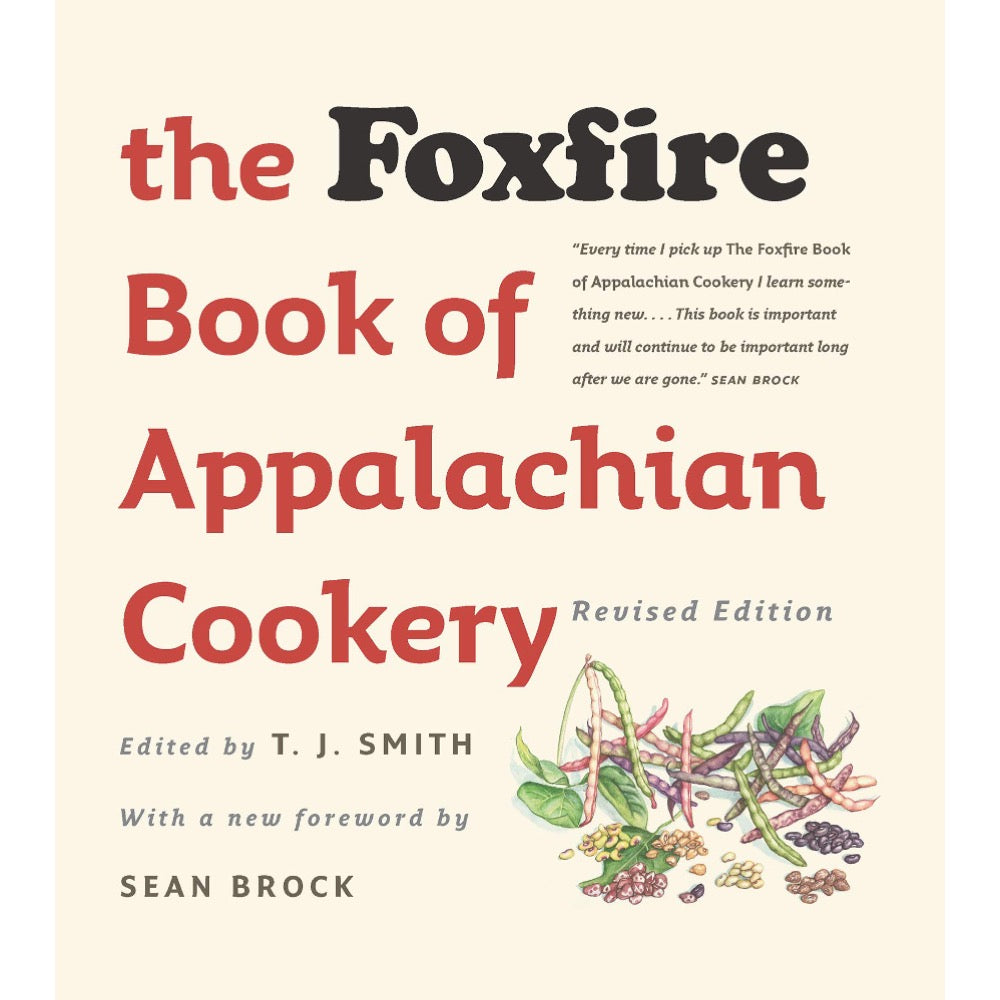

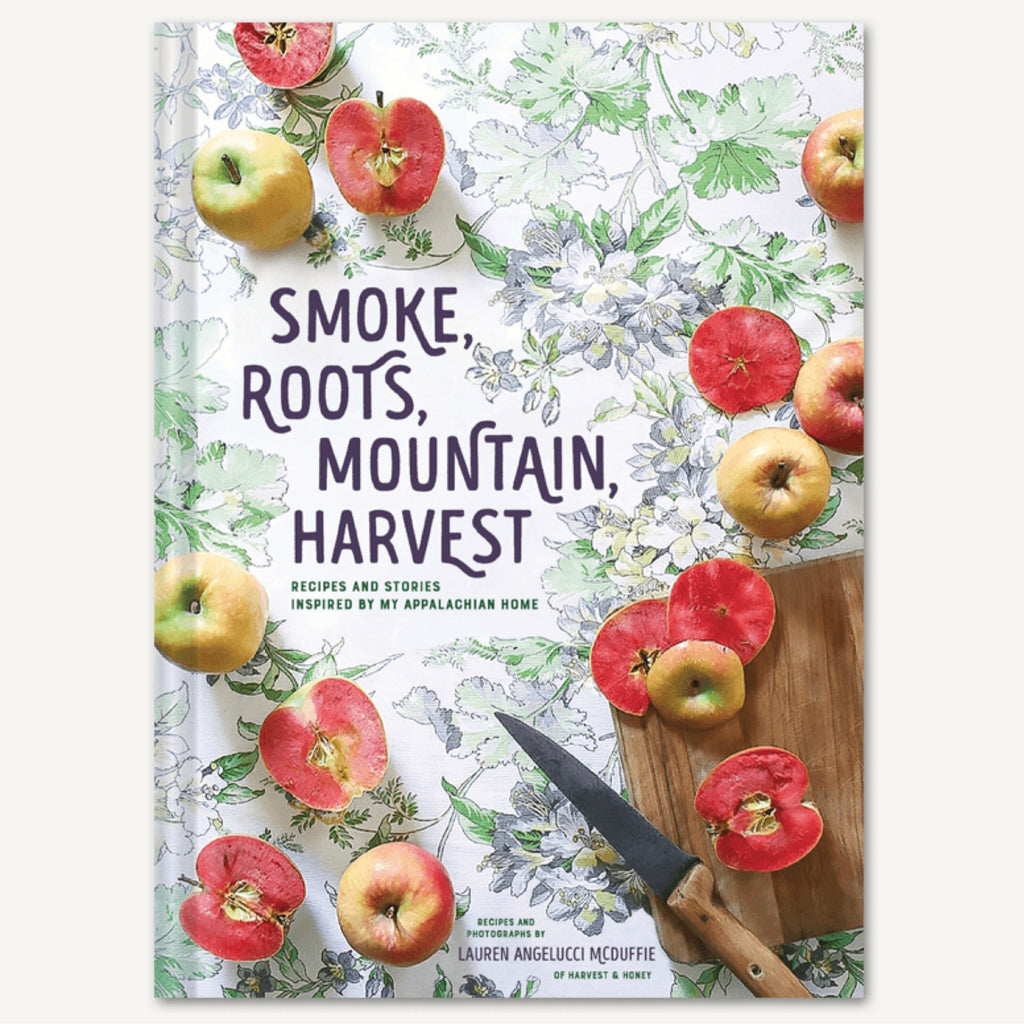

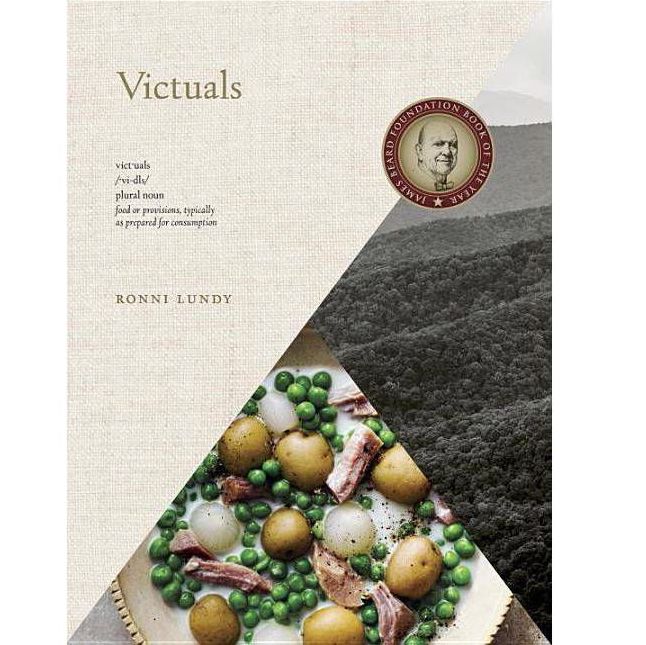

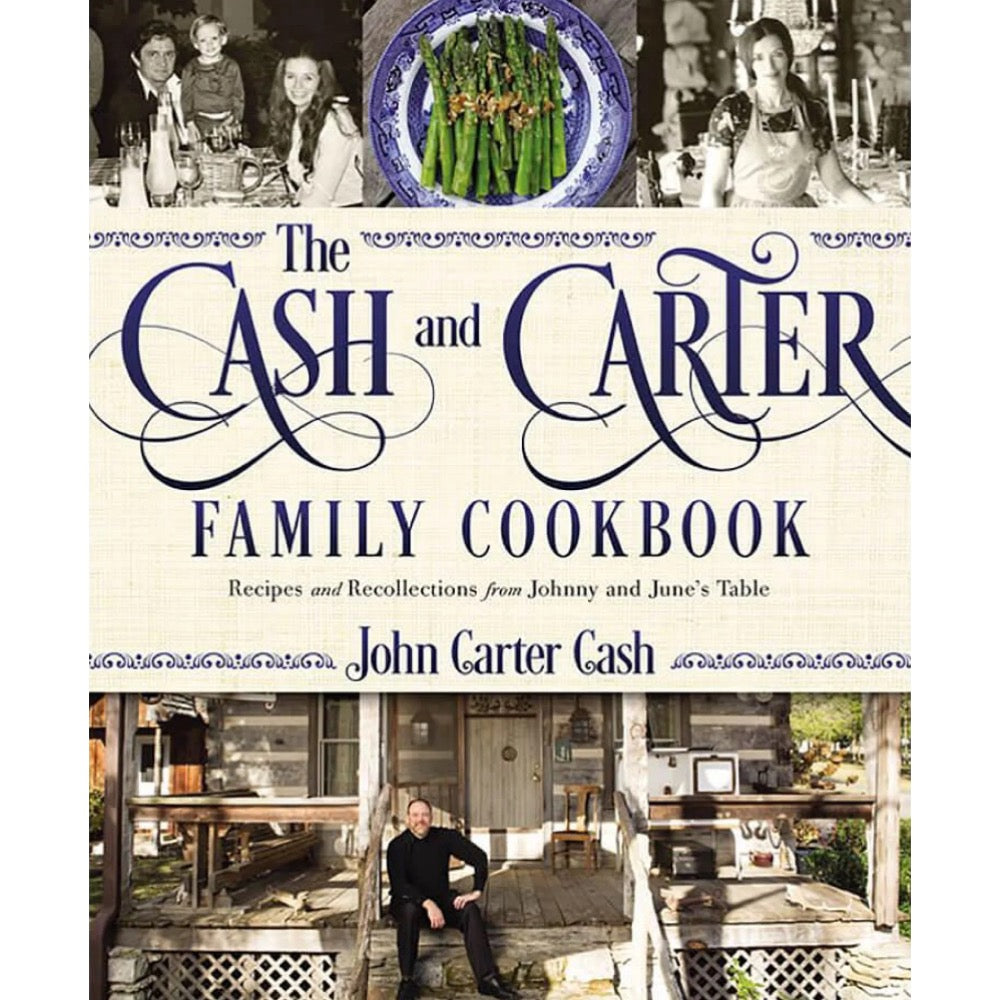

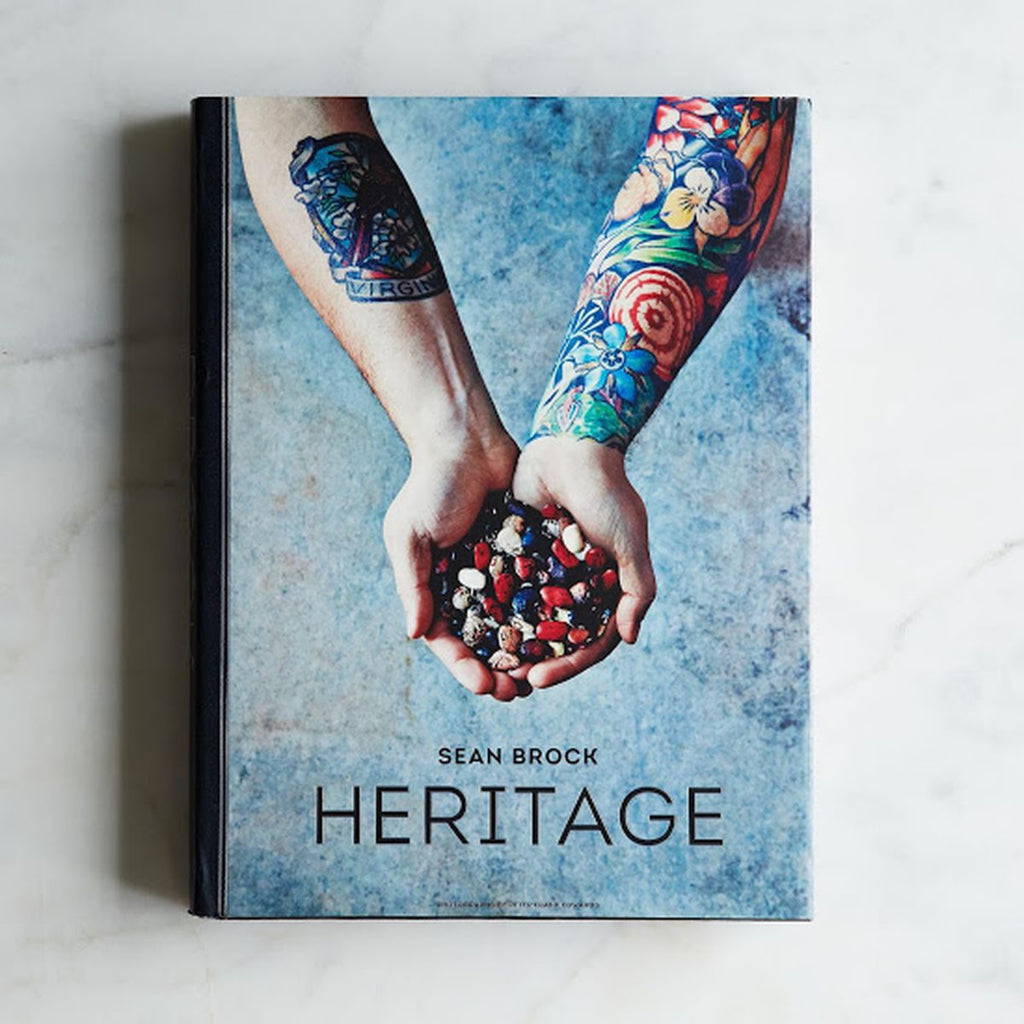

“If you love to cook, check out Sean Brock’s South, a follow-up to his award-winning Heritage. Born and raised in the Appalachian mountains, Brock is known for his endless creativity...Now he’ll also be known for two of the decade’s most beautiful and authoritative Southern cookbooks.”

Southern Living

(Every purchase helps keep our Appalachian magazine alive and thriving.)

According to his peers, this commitment to authenticity and flavor has defined Sean’s career. “When working on a new dish, I remember him saying, ‘It has to be delicious,’ that presentation and the details would come later,” said Brian Lee, who worked at Sean’s now legendary Charleston, South Carolina restaurant Husk. Brian now co-owns Kisser, which serves Japanese comfort food in Nashville. “As obvious as that may sound to some, it was the first time I had heard a chef in the fine-dining world say that or approach a dish that way, and it’s been my primary approach ever since.”

Since then, Sean has opened a slew of other Southern restaurants and written several books, including one called “South” that focuses on the region’s many food traditions, from the Gulf coast to South Carolina’s Upland. But one of his career highlights came in 2021, when he opened the Appalachian-themed Audrey in Nashville. Named after the grandmother who first inspired him to cook, this unique eatery reflects his abiding love for his homeland and the foodways he learned there. “When I was naming this restaurant,” he says on the restaurant’s website, “the one where I want to spend the rest of my life cooking, naming it after her was an easy choice. I didn't consider anything else.”

Now in what Sean calls “the second half” of his career, he is dedicating himself to “untapped traditions and discoveries,” looking to places like Japan for inspiration — which brings us back to kudzu.

Sean told the Wise County audience that, in Japan, kudzu root is dried and then a starch is extracted from it. Chefs pay $80 a pound for the starch, simply called kuzu starch, which is packed with flavonoids and antioxidants and is used in broths and even desserts.

Meanwhile, in the U.S., landowners struggle to eradicate kudzu. It was brought here for erosion control — which worked — but it is an invasive fire hazard and difficult to remove. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, it can take 10 years of persistent herbicide applications to fully eliminate kudzu and two years with a combination of organic bioherbicides.

“My next big idea that I’m so excited to focus on for the next half of my life is the taming of kudzu. We’re gonna call it the ‘war on kudzu aggression,’ ” he told the audience with a laugh.

APPALACHIAN INGREDIENTS

The Japanese actually hold kudzu festivals, which remind Sean of the Virginia potlucks he attended as a kid. He’d like to leverage Appalachia’s climate and traditions to make better use of this omnipresent crop.

But this is just one part of Sean’s vision for Appalachian foods. The relative youth of the Appalachian cuisine we know today — as compared with Japan’s or even Europe’s — gives Sean hope that new discoveries are still ahead for the region. He gives the example of balsamic vinegar, which was discovered in an Italian town after it had already existed for 1,500 years. “I think we have some balsamic vinegar ahead for us in these forests.”

Forests and fields already provide so much of what is served at Audrey, where menus are seasonal and may include greasy beans, killed lettuces, sour corn, and other dishes that would sound familiar to those who grew up in Wise County. They’re presented with an artistry that is uniquely Sean’s, such as rosin potatoes served in a basket made from — wait for it — kudzu vine.

Sean estimates that 80% of the time at the restaurant is spent looking for ingredients, including those that may be lost. Sean is widely credited for helping to bring Jimmy Red Corn back from near extinction. He also encourages folks to continue to plant the brown pole beans known as leather britches. Selecting ingredients, he said, is akin to a wine pairing, “looking for different ways of weaving flavors together.”

Sean credits his grandmother with instilling this appreciation for local, seasonal ingredients. She also taught him to be resourceful, which meant never throwing anything away, a value he said could border on hoarding if he is not careful. “She did things the old-fashioned way. She had a crank-start, 1940s tractor like you would see in a cartoon.”

Thanks to her, Sean could identify ramps and morels as a child. “It was almost biological how we knew them,” he said. “That is how I was wired.”

GET TO COOKIN

He also remembers sitting on his grandmother Audrey’s screened-in back porch listening to people tell stories or sitting at a kitchen table with just-picked blackberries or pawpaws. “I stayed in the middle of that tiny kitchen. That is where all the action was, not her living room.”

“If you look at Appalachian food, nothing like it in the world,” he added, noting that chefs and specialty store owners would gladly stock fermented corn on the cob, sauerkraut, and other local specialties. “I know that Whole Foods and other grocery stores would line up for apple butter from Wise County,” and he wants to help preserve that canning culture.

As food-centric as Sean’s life has been, folks are sometimes surprised to the depths of his other interests. In recent years, he’s been drawn to photography, especially the work of Southern photographer William Eggleston, who is known for capturing everyday scenes — “photographing the boring” as Sean calls it. Like Eggleston, Sean is using discipline to only take a single image, one that doesn’t have to be edited, getting it right the first time.

That drive to do things thoughtfully is another trait he learned from his grandmother in Wise County. He calls is grit. “It’s a grit geared towards doing the right thing and really trying to focus on taking the best care of the person beside you that you can. It’s an extraordinary generosity that lives here that I try to carry on in my restaurants.”

A version of this story first appeared in Cardinal News.