WRITER JESI OWENS BRINGS EDNA LEWIS' CLASSIC APPALACHIAN RECIPES to life. PHOTO BY JESI OWENS.

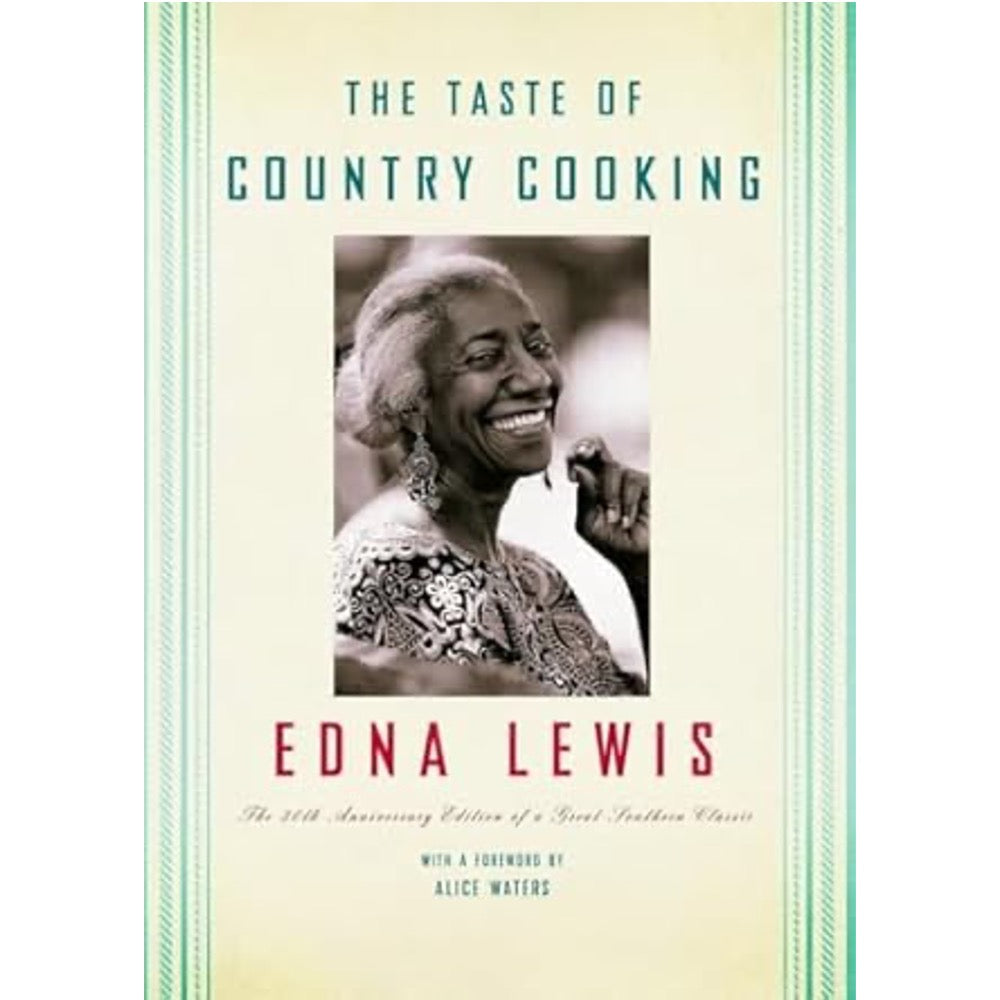

"Ham held the same rating as the basic black dress. If you had a ham in the meat house, any situation could be faced."

— Edna Lewis, chef and fashion designer

Edna Lewis knew a thing or two about food, fashion, and facing new situations. She was born in Freetown, Virginia, a mountain hamlet that was founded by her grandparents, emancipated slaves with roots deep in the soil they eventually owned. The seasons guided their daily lives and shaped Lewis’s understanding of local ingredients and what we now call "slow food."

A spunky, yet practical artisan, she took her Appalachian knowledge and explored the world, first moving to Washington, D.C. and, soon after, New York City. Think of your mamaw — her cooking, sewing, and storytelling. Think of what it would be like to bottle that heritage and take it wherever you go in the world, a taste of home anywhere you may roam. From an early age, Lewis was able to conjure the halcyon atmosphere she remembered from Freetown and bestow it onto those around her in big cities and big social scenes.

She first made a name for herself in New York’s post-war, avant-garde community, designing fashions for the likes of Marilyn Monroe and throwing dinner parties from Brooklyn to Harlem. Her ability to draw from her mountain roots and her personal wit and charm led her to co-found the iconic Cafe Nicholson in 1949. At this now legendary New York restaurant, Lewis served the likes of Salvador Dali and Tennessee Williams. Truman Capote famously befriended her, and she made him biscuits like the ones he missed from his Alabama home.

She went on to helm other iconic restaurants up and down the East Coast, write books, and founded an organization that eventually became the Southern Foodways Alliance.

Now, a feature-length, PBS documentary, “Finding Edna Lewis,” gives Lewis the attention she deserves.

“It was one of those things where it was like, ‘Why have I not heard from her?’” explained Deb Freeman, a food historian and writer who happened upon Edna Lewis around a decade ago from a simple Google search. “Why is she not a household name?”

In a 2017 episode of Top Chef, contestants, including some Black, Southern chefs, were asked if they were familiar with Lewis. None were.

Seeing that Lewis had been overshadowed by newer celebrity chefs, Freeman partnered with two TV producers to raise the once-legendary chef’s profile.

“Finding Edna Lewis” takes viewers to Brooklyn, Savannah, Charleston, and back to Lewis’s Blue Ridge hometown, where we join Bethel Baptist Church’s annual homecoming dinner. (It’s a scene any mountain Baptist will recognize - the hats! the wet salads!) Along the way, we meet a cast of female chefs, writers, historians, and more who have rediscovered Lewis, demonstrating that her uniquely Virginian style of cooking — for the community and with great care — transcends time and place.

A PRINT OF MISS LEWIS IN THE WRITER'S KITCHEN. PHOTO BY JESI OWENS.

And then I tried to cook Like Edna Lewis.

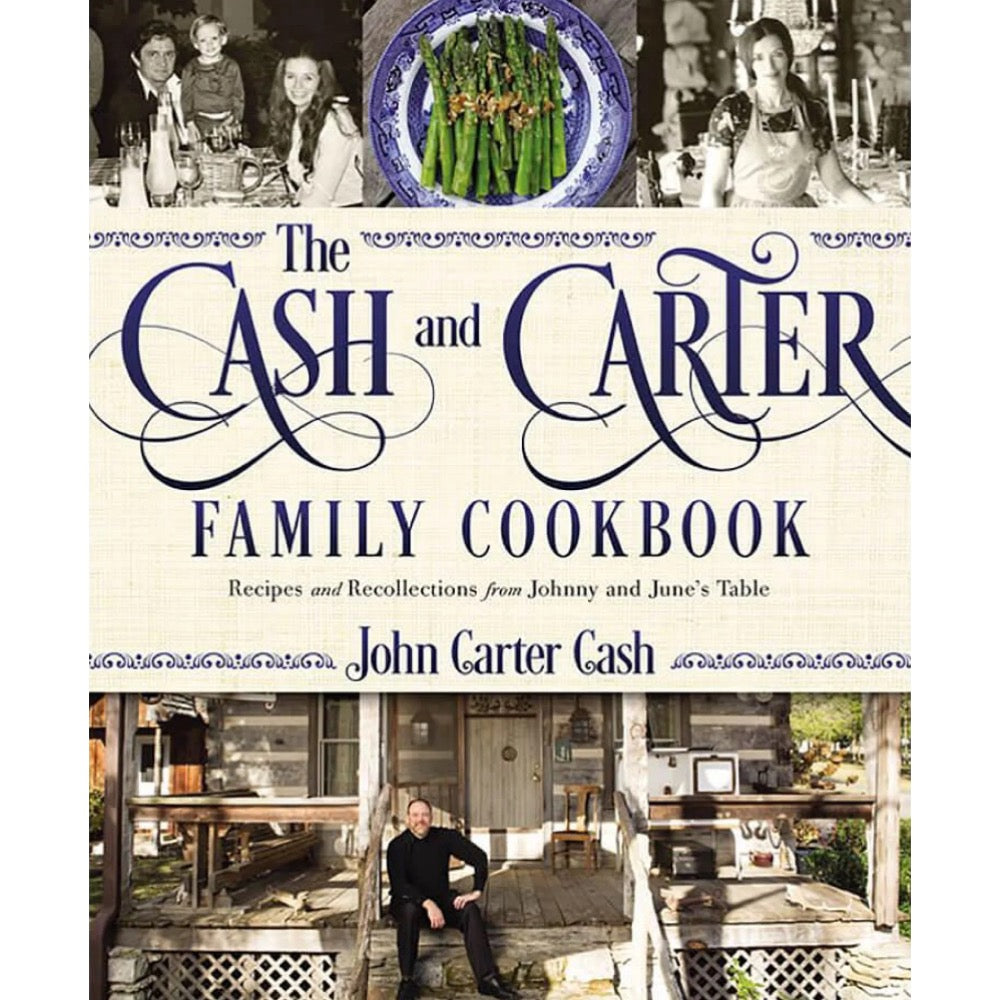

Ms. Lewis’ seminal book “The Taste of Country Cooking,” released in 1976, focused the world on Southern food and, even more specifically, food from Virginia's mountains. (My well-worn copy sits on my kitchen shelves near an original print of Miss Lewis and my Mamaw’s canned green beans.) Part of the book’s charm is that it transcends a simple cookbook with beautiful stories and prose. It’s a memoir, an ode to a rural way of life that still influences me. As a woman who lives in a Virginia holler yet frequently finds herself on airplanes or in concrete jungles, the constant tug of modernity creates a struggle to stay rooted in traditional, Appalachian ways of cooking and living.

Lewis’s passage about the start of a warm day is particularly inspiring:

“A warm morning and a red sun rising behind a thick fog gave the image of a pale pink veil supported by a gentle breeze that blew our thin marquisette curtains out into the room, leaving them to fall lazily back. Being awakened by this irresistible atmosphere we would hop out of bed, clothes in hand, rush downstairs, dress in a sunny spot, and rush out to the barn to find a sweet-faced calf, baby pigs, or perhaps a colt.”

She also explains that her family literally repainted and wallpapered their homes to host out-of-town relatives during their annual Homecoming, and that, for children, shoes were primarily worn during cold months, particularly for school, and that the removal of shoes on "Spring Chicken Day" was a significant event marking the start of the coming barefoot summer.

Inspired by the world Lewis conjures, I rolled up my sleeves, put on my apron, and began work on a menu from Lewis’s childhood.

All this nostalgic imagery inspired my meal planning, but almost immediately, I hit barriers. Many of Ms. Lewis’ traditional ingredients just aren’t available to our modern Instacart lifestyles. In trying to hunt down the native root salsify, I spoke to restaurateur friends as far as four hours away. They get their salsify from New Jersey and California. When I asked Freeman, the documentary’s host, about the loss of local ingredients she said, “Where I'm from, in Hampton Roads, our seafood isn't local, even though we're right on the water.”

Freeman noted that farmers markets are a good source, but in many cases, those committed to farm-to-table resort to growing traditional ingredients themselves.

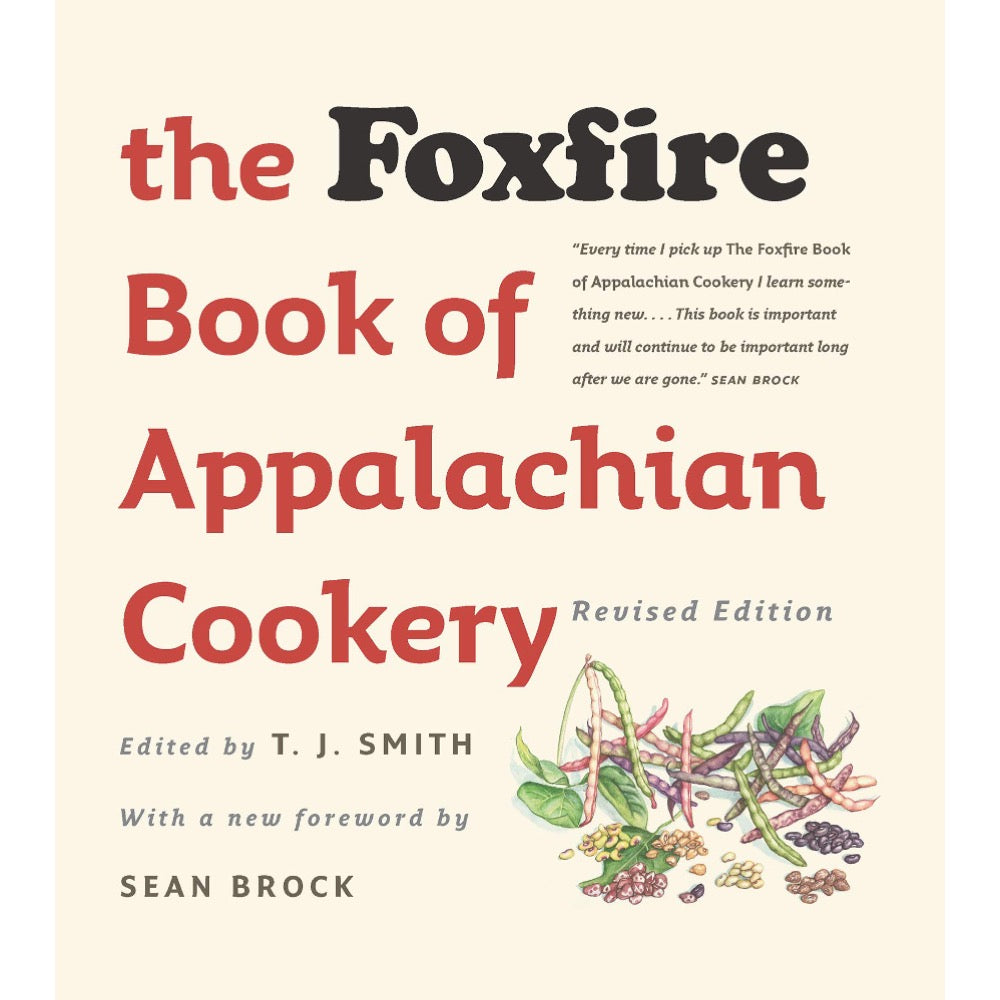

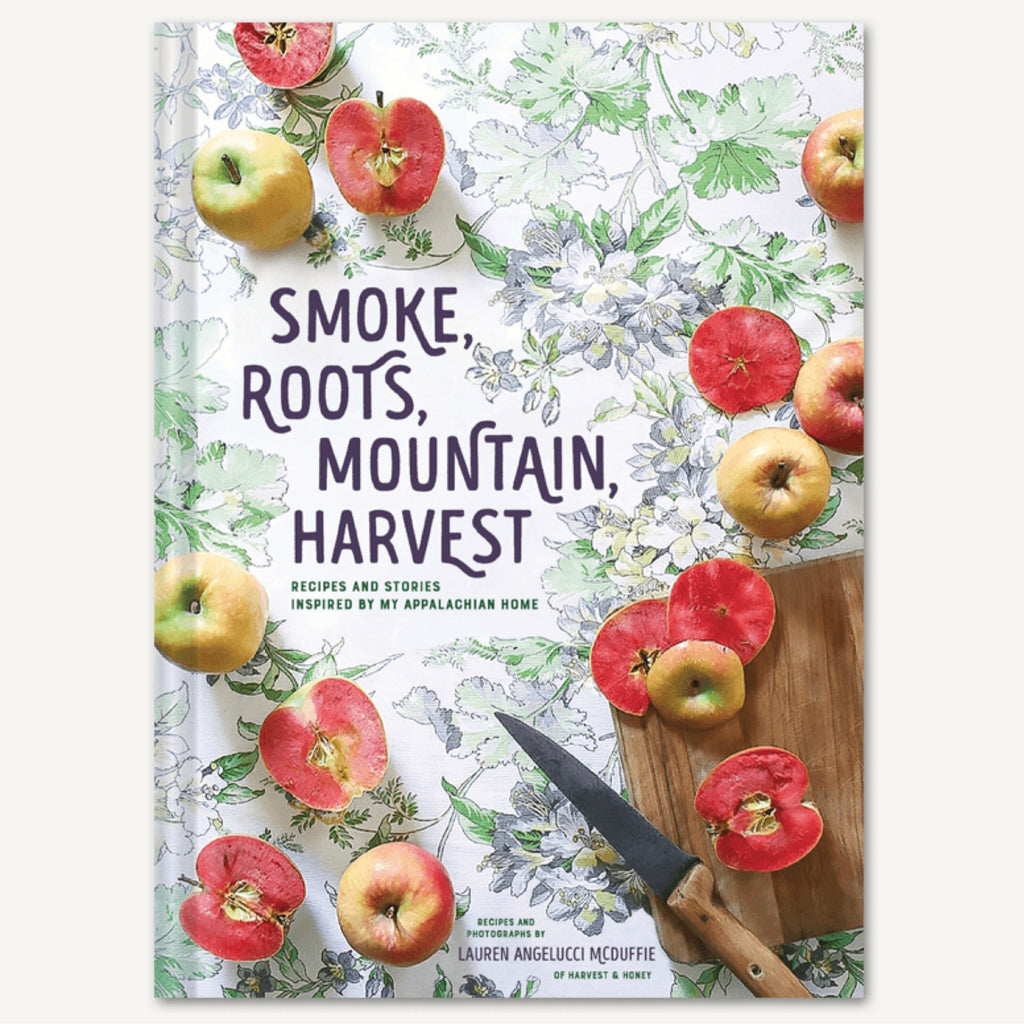

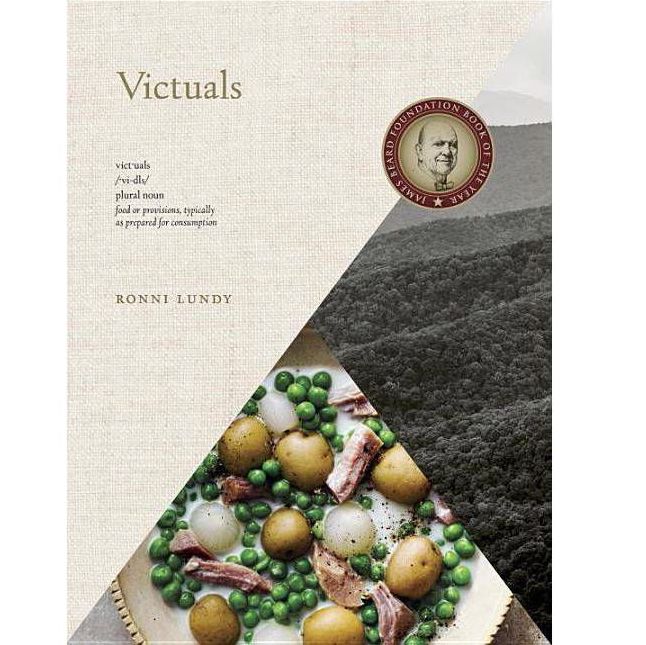

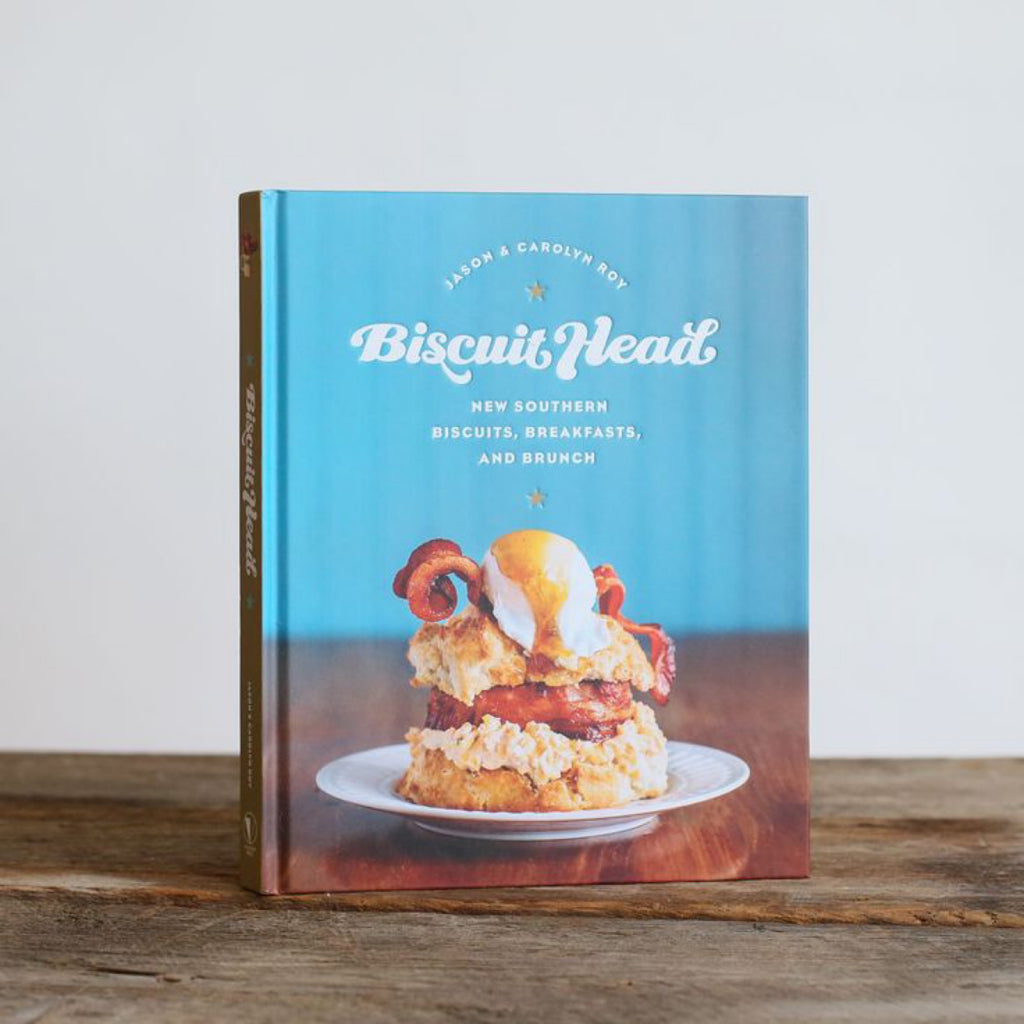

GET TO COOKIN'

Every purchase helps keep our Appalachian magazine alive, thriving, and free to readers like you.

Luckily, I was able to obtain a bounty of spring mushrooms from Appalachian farm Den Hill Farm & Fungi and other local ingredients from Christiansburg Earth Fare (which commits to sourcing within 100 miles of its stores). So I was able to cobble together what I needed for my spring menu, drawn entirely from “The Taste of Country Cooking” — Skillet Spring Chicken with Watercress served with Rich Wild Mushroom Sauce, thinly sliced Skillet Fried White Potatoes, and Skillet Wild Asparagus. For dessert, I made Special Butter Cookies (which are actually ginger cookies!) with Strawberry Preserves.

On a late March Sunday, I finished cooking and sat down with my husband to a beautiful spread, a meal that was both delicious, thanks to Lewis’s culinary prowess, and also meaningful. My chicken, vegetables, and even my cookies were tangible connections to a time when meals were dictated by the seasons.

So many things struck me as I ate, starting with Ms. Lewis’s relationship to dairy. Butter, cream, and milk are everywhere in her recipes. I’ve made chicken and fried taters a hundred times, for instance, but I‘ve never deep fried them in butter and then used that butter to make a mushroom gravy to pour over it all. Highly recommend!

And while I used Kerrygold, I so wish I could try the sweet fresh cream from Lewis’s father’s cows. Those animals ate grass from the same soil that sprouted the family’s strawberries and asparagus, connecting ingredients from deep within the Earth in a way most of us will never experience.

Another thing that stood out: As I was attempting to measure up to Lewis in the kitchen, I felt like I do when trying to master one of my own mamaw’s recipes. These women cooked from ancestry, from memory, from taste and feel. It’s sensory, and no exact instruction will get you there.

Though my dishes may not have been perfect replicas of those in Lewis' book, they did connect me to her kitchen and to our our shared Appalachian heritage — plus a legacy of foodways and crafts, of connection to nature, of family and friends that every mountain person carries with us, wherever we go.

Jesi Owens is a proud Appalachian from Grundy, Virginia who writes about cultures of all kinds with a special interest in her native Virginia. She splits her time between restoring the 1834 Blue Ridge cabin Airbnb she runs with her husband and traveling the globe.