Buried in the way things are lies a hidden truth about the way things used to be." From the new introduction by Toni Tipton-Martin

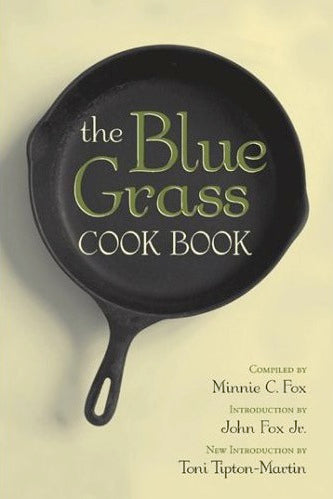

Originally published in 1904 , the cookbook was compiled by Minnie C. Fox, a wealthy matron who was originally from the plantation dotted fields around Paris, Kentucky and, later, the emerging coal country of Big Stone Gap, Virginia. She was the daughter of a successful educator. Her father was a schoolmaster, devoutly religious, and sensitive to suffering in any form. Her brother was the Harvard educated novelist, John Fox Jr.

It would have been easy and obvious for Minnie to write a cookbook like others at the turn of the century. Church and civic groups published recipe collections that attributed all culinary innovations and the entirety of their content to well-to-do white women. They rarely acknowledged a truth that would have been evident to anyone at the time--family recipes or not, these women didn't create these dishes, at least not on their own.

Behind every mistress was a Mammy, an Aunt Dinah, and countless others black domestics who defied archetypes. While they were free to leave after the Civil War, many stayed to rear white children, feed families that they'd known lifelong, cook, and clean. It was the work they knew, and leaving was complicated. While never equal to the families they served, there was often a mutual affection.

"To that turbaned mistress of the Kentucky kitchen gratefully this Southerner takes off his hat," wrote John Fox, Jr. in the original introduction to The Blue Grass Cook Book. He voiced what many whites must have known if not acknowledged--that white society owed its thanks to black servants.

"To that turbaned mistress of the Kentucky kitchen gratefully this Southerner takes off his hat," wrote John Fox, Jr. in the original introduction to The Blue Grass Cook Book. He voiced what many whites must have known if not acknowledged--that white society owed its thanks to black servants."Her realm was not limited to the kitchen," he added, continuing his praise for the unsung cook. "There were times when all, black and white, bowed down before her."

Starting with this bold introduction from her brother, Minnie Fox acknowledged all of the book's contributors. Some were from the "best" families in Kentucky and western Virginia; others worked for them. She chose to illustrate her book entirely with photos of black women and men at work preparing foods.

It was no secret that blacks and whites collaborated to uphold the lifestyle of the gentry. Even with stark inequalities, they labored and lived beside one another; their children played together; they sustained one another.

For some families, like the Foxes who remained true to their father's sensitive nature, this created a reverence for those who served them. At the same time, there was a growing wave of segregationist sentiment when Minnie's book was released. It would lead to the revival of the Ku Klux Klan eleven years later, but already whites were trying to reassert their authority over blacks in the South.

In the short term, this force may have won out. In spite of being published in New York with an introduction from a popular author and photos from an internationally recognized photographer, The Blue Grass Cook Book was a flop.

"Newspapers of the time ignored it, and even when Minnie Fox died almost sixty years later, her published obituaries made no mention of the book," wrote Toni Tipton-Martin who revived the cookbook one hundred and one years after it was originally published.

Her new edition, which details the book's enthralling history, is the one that appeared under my Christmas tree. It now sits in my kitchen beside other cookbooks--The Joy the of Cooking, Whistle Stop Cafe Cookbook, Mastering the Art of French Cooking. All of their authors enjoyed a commercial success that eluded Minnie Fox but none were so daring.

With recipes, this white matron pulled back the curtain of the Southern aristocracy and revealed a hidden truth. Some well-off whites cared deeply for the people who served them, and some black servants held an invisible authority that nearly no one ventured to put in print.