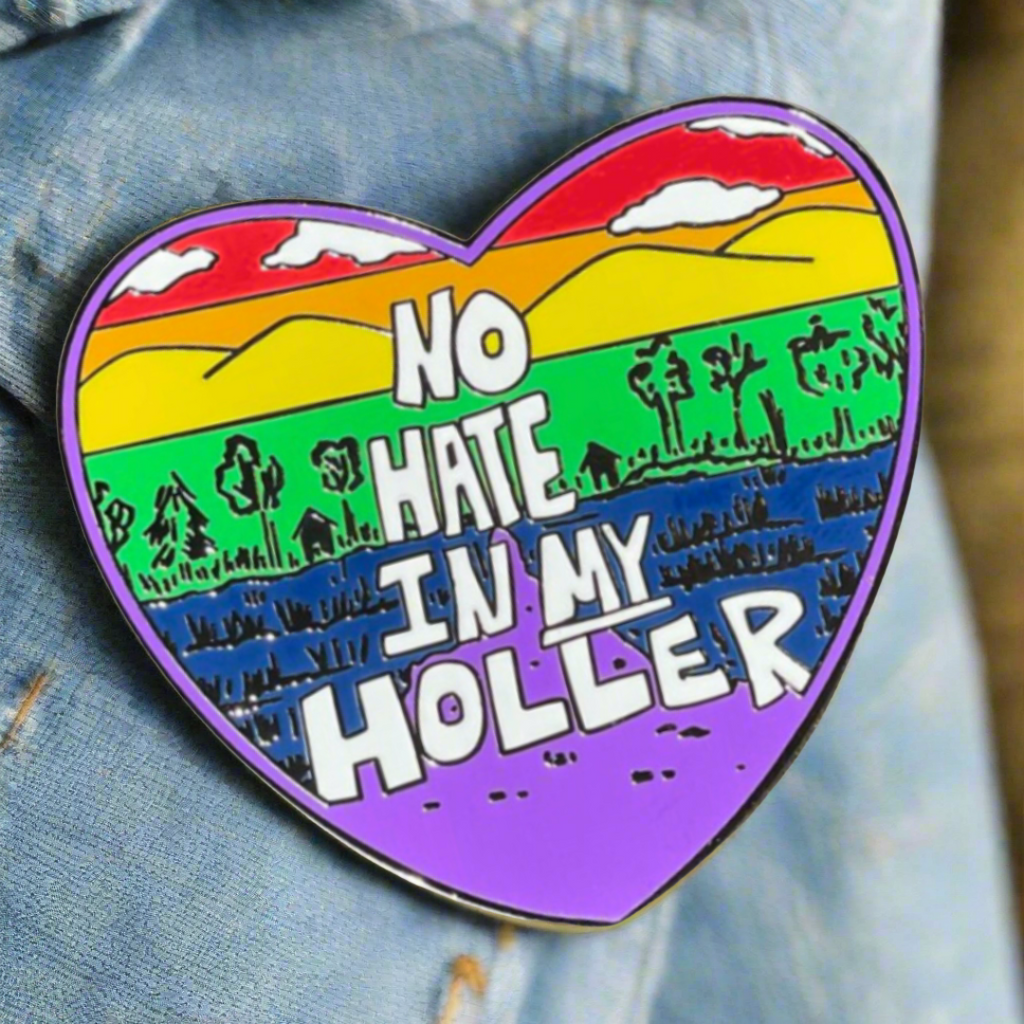

Cover art for the paperback EDITION of “Lark Ascending.”

"I was lucky to be a boy who was able to roam the woods. We played in the creek, and we were always out in the hills. I'm amazed, looking back, because I never remember coming up on a snake or getting hurt or anything, never."

This is the second part of our interview with author Silas House about his newest novel — set approximately twenty years from now. “Lark Ascending” shows humanity at its best and worst, in the context of a calamitous future. The novel centers on one family that’s been forced to leave Appalachian Maryland, which has been made uninhabitable by extreme changes in climate and a political insurrection. Civilization crumbles, and the family seeks sanctuary in Maine’s mountains. When even that remote land becomes dangerous, they board a refugee boat headed for Ireland. But Lark is the only one who arrives alive. Alone and swallowed by grief, he remains determined, stumbling overland in search of a place his parents mythologized, a refuge.

During his journey, a new character appears — Seamus, who may be Ireland’s last living dog. Massive food shortages have prompted people to kill their pets so they don’t compete with humans for food.

What follows is a dystopian novel, where wildness reemerges on the earth and, in crisis, humans’ base instincts — good and evil — surface.

“It's a very different kind of book for me,” says Silas, who’s been writing Appalachian novels for over two decades, “in that it's in the future and mostly set in Ireland. But I've always been writing about community and the natural world and created family. Those three themes go through all my work.”

SILAS INTERVIEW PART ONE:

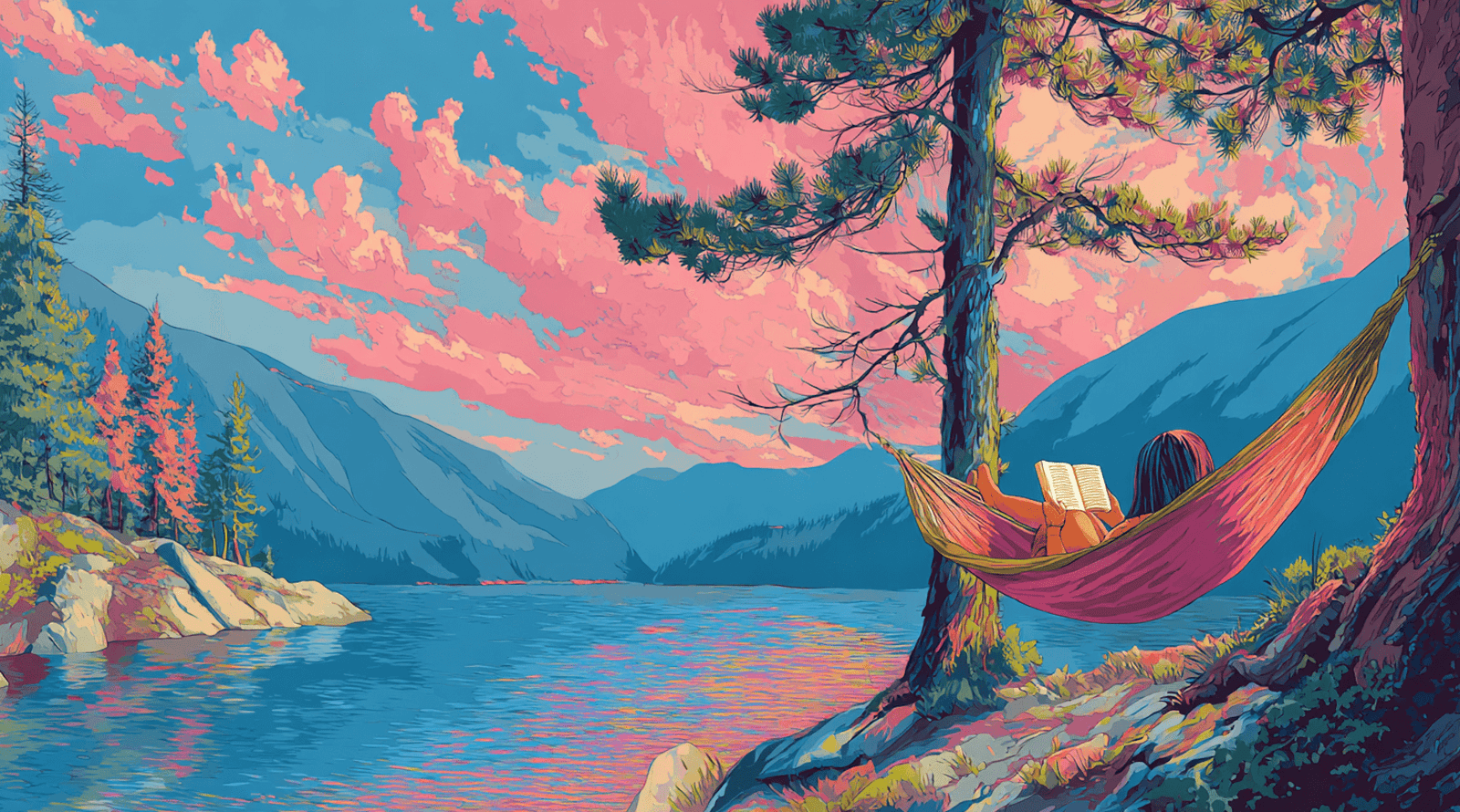

Place is foundational to this book — Appalachia and Ireland. It’s also important to many writers in their own lives. I’m curious to hear about your ideal setting for writing. Do you have a writing desk, favorite chair, or a room where you always write?

I have an office. I call it my “writing room.” However, I don’t usually use it for writing. We have this big porch that overlooks the creek and the woods, and it’s surrounded by trees. We let a lot of it grow wild. Just having a wild yard connects you so much more deeply with the natural world than if you mow everything down. I write [on the porch] as long as I possibly can.

When I’m not on the porch, I’m usually by the fireplace, on the couch because my beagle can be beside me. He’s usually as close as he can get, sometimes uncomfortably so. I’ve always loved having dogs as writing assistants. They give you such good vibes, you know?

And when I’m outside, the dog is usually lying on the floor beside me, or he follows the sun, wherever he can get a good, warm spot. But the main thing is the comfort of the natural world, having an animal and a fire close.

I can relate to needing those elements nearby. Speaking of the natural world, it plays a central role in this book and many of your others. Can you say a bit about why?

I was lucky to be a boy who was able to roam the woods. We played in the creek, and we were always out in the hills. I'm amazed, looking back, because I never remember coming up on a snake or getting hurt or anything, never.

Now, people have a lot of fear associated with the woods and the natural world. I hate that. It was never scary to me. It was a place of safety and freedom, and I'm always trying to recapture that in my work. Lark has never been afraid of the woods. In fact, he uses the natural world to hide from roving militias. It's a place of protection, not fear.

"With 'Lark Ascending' House reveals himself to be an oracle from the future who has come back to illuminate our lived moment...The vision is terrifying and spare, but in House’s capable and delicate telling, it is also beautiful and compelling."

Wiley Cash,

New York Times bestselling author

(Every purchase helps keep our Appalachian magazine alive and thriving.)

And these characters are in the wilderness so long it changes them.

Yes. When we think about the future, we're often thinking about technology. My vision of the future is wiping out technology. Instead of flying cars, the wild comes back. People are in small clans, living together, trying to survive. They tell stories around the fire. They sing. They're agrarian.

The whole book, [the characters are] aiming for this settlement, this community, but once I got them to this gathering of like-minded people, I thought, “But wait. They have found real beauty in the wild.”

There's one passage I’d like to read:

[We realized we were] not fit for society. We were people of the hazel trees and cedars, of cold creeks and wide pastures. We were the trout that swim in the darkest reaches where no one can betray us. We had more in common with rocks and rivers than we did with people now. We had seen what happened when people lived together in too big a clump. The better choice was to live with a handful...

The older I get, the smaller my circle becomes. You realize it doesn't have to be how many friends you have. It's more about how good the friends are.

I agree. You mentioned singing. I love the way you use songs and lyrics in this novel.

Lark doesn't remember electricity, so he doesn't remember recorded music. I thought a lot about that. I would be the age of Lark’s parents, so if I hadn't heard recorded music in twenty years, what songs would I still be able to sing?

I’d definitely know John Prine’s songs by heart. I wanted some pop songs too. I could probably still sing some Adele, Avett Brothers, some U2, and Brandi Carlile. I really liked thinking about that — what would stick with me that I could still be singing.

Speaking of verse, there's so much poetry in this book, and I haven't yet mentioned you being named Kentucky’s poet laureate. Congratulations! Do you see yourself as a poet?

I mainly identify as a novelist — I'm most satisfied by a novel — but I've always written poetry. For me, poetry is the highest form of literature, mainly because it's the most difficult. I know poems that contain as much emotion and as much provocation of thought as a whole novel. That's incredible.

So maybe you’re a novelist who puts poetry in his novels?

Besides music, the number-one thing that shapes my novels is poetry. When [a novel] starts to take shape, I make a playlist. I start curating the music. But I also look at the poetry that is going to shape the piece of work. For this book, I was looking at Irish poets, but also a lot of agrarian poetry because there is a big agrarian theme.

KENTUCKY'S FINEST

You’re a novelist and a poet — and a great source of new music. Will you please tell me what you're listening to lately?

I'm really loving this new country singer named Brit Taylor. She's from Eastern Kentucky and it just sounds like the country music I grew up on, like Patty Loveless.

Jason Isbell's new album is one of his best. “Middle of the Morning” [is] just one of the best things he's ever written, “Cast Iron Skillet,” too.

As far as mainstays, an artist I have always loved — I can barely talk about her without getting choked up — is Sinead O'Connor. She was right about everything, and they crucified her for it. They absolutely destroyed her. But she was right, and I just love that about her. I just wrote a poem called “Ode to Sinead O'Connor” about the way that, so often, women are torn down and then later proven right.

That can be said of queer people too. And, in your novel, Lark is gay. He lives in a world where he could be killed because of his sexuality but, for years, his family and another family live in this self-made enclave in Maine. That gives room for love to bloom between Lark and his friend Arlo. How does that compare to your own life as a gay man from Eastern Kentucky?

Well, Lark is lucky he has accepting parents. I didn't have that. It took my parents about ten years.

Becoming poet laureate, for instance, I have been overwhelmed by the love — just waves and waves of love. On the other hand, there's been so much homophobia, people saying it's a “diversity hire” and things like that. One of the paradoxes for me is living in a state where there's hateful legislation and juxtaposing that against people I know to be so individually loving and welcoming.

To me, this is the only reason to set a book in the future — to emphasize “this is already happening.” Everything is already in motion. Women have fewer rights today than when the story was published, et cetera.

But what gives me hope is that human beings are mostly good. I hope that we retain our humanity as much as we can in the face of crisis.

This interview has been condensed and edited.