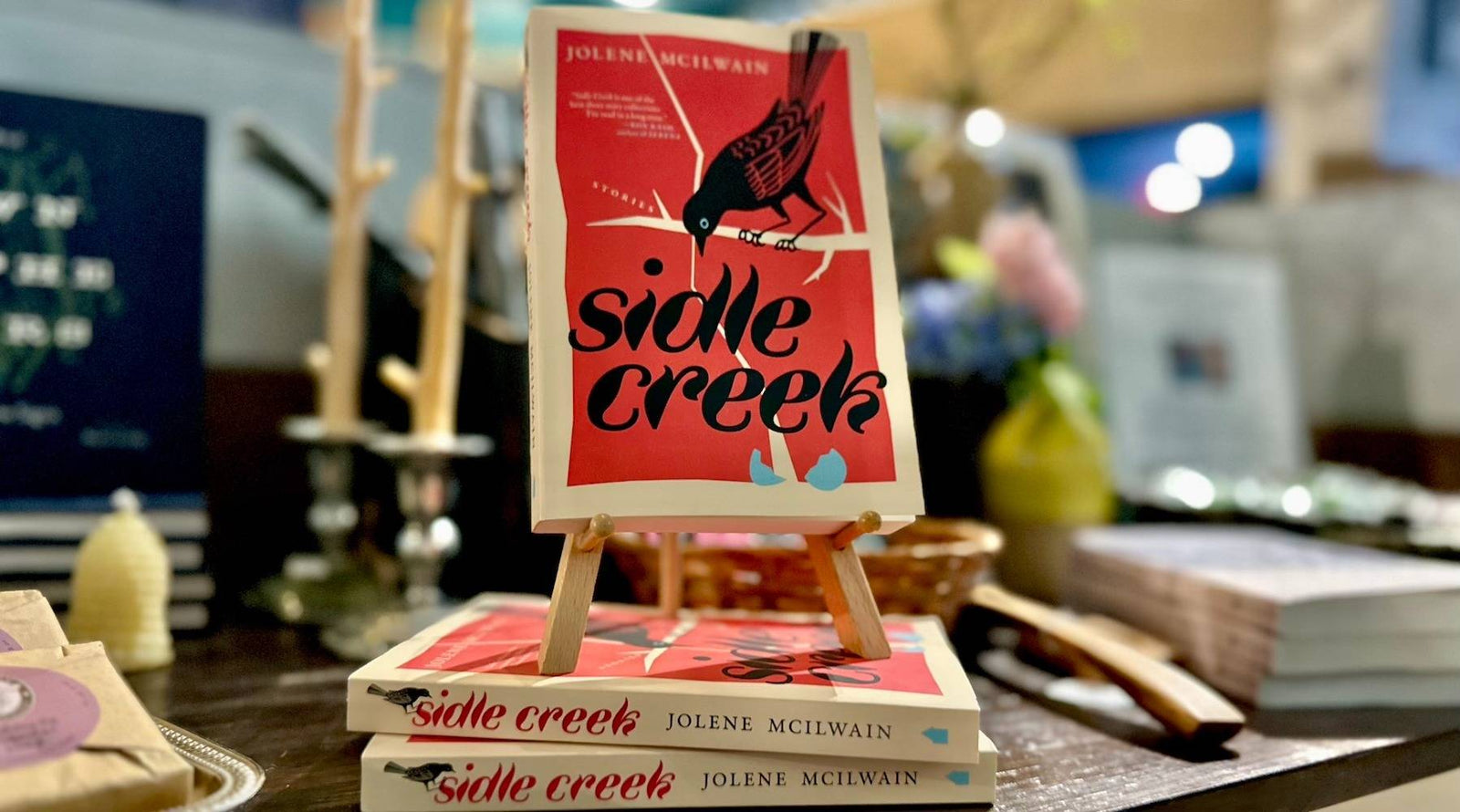

SHOT BY MARK LYNN FERGUSON IN OUR ROANOKE, VIRGINIA SHOP.

They told her to leave Appalachia and never look back. She stayed and wrote an acclaimed anthology.

Growing up in Kittanning, a small village in the Appalachian plateau of western Pennsylvania, Jolene McIlwain always knew she’d have to choose. On her 18th birthday, she’d either have to pack up and leave behind the mountain soil or stay rooted in a place often deemed depressed and deprived.

“In the end,” Jolene said, “I stayed.”

Today, despite all the naysayers who warned her about getting stuck in her sleepy hometown, Jolene is thriving in Kittanning. That much is evidenced by “Sidle Creek,” her short story anthology reviewers are describing as tender, terrifying, and thrilling. It has also been named an NPR Book of the Year.

This lauded collection takes readers to the “timbered and mine-bruised landscape” of western Pennsylvania. There, on the banks of the eponymous stream, Jolene brings to life a hardscrabble cast who illustrate a “genuine rural community … instead of perpetuating the strong held myths” about Appalachia.

In one story, “The Fractal Geometry of Grief,” a man named Hubert falls in love with a doe-eyed whitetail deer after his wife’s death. Jolene said she began writing the piece more than a decade ago while coping with “the reality of losing loved ones to heart attacks, strokes, Alzheimer’s, and tragic accidents.”

Amid her heartbreak, the writer befriended a herd of deer. “I wanted desperately to be nearer to them in some way,” she said, “to keep them safe from harm.”

These themes come together to create a deeply lyrical story that Jolene hopes will cause readers to “fall in love with the place, the people, the animals, the flora and fauna, the bodies of water, in much the same way I’ve fallen in love with the place that inspired the fictional Sidle Creek.”

From “The Fractal Geometry of Grief,”

a short story in “Sidle Creek”

BY Jolene McIlwain

Hubert Ashe fell in love with the doe in August, four months after his wife passed.

He told no one about the deer until October when he called to inform his son, Will, he wouldn’t be joining him for Thanksgiving. He wouldn’t feel comfortable leaving the cabin and the deer behind. Who would put out apples? Who would sprinkle corn?

“Are you sure, Dad?”

“Yes, I’m sure.” Hubert gazed at the laptop’s screen, the trail-cam photos. His doe. He traced the white band around her nose. Clicked to the next shot. Touched her throat’s white patch.

“But I don’t want you to be alone, Dad.”

“I’m fine,” Hubert said. It was Will who was alone. Still single, in his late forties, he’d stumbled through relationships, never having unearthed a love that would sustain him.

Hubert closed the trail-cam file. Home screen appeared. Genevieve’s seventy-third birthday. Two days before Easter. Their last holiday together, posing in front of the redbud’s shocking pink blossoms.

Hubert’s wide grin, disheveled hair, glasses crooked on his crooked nose. Will beaming, so tall, between them. Genevieve with her new white silk scarf tied at her throat, nearly matching the snow-white her once ginger hair had become. Her hand clutching a leaf. She was gone by the time the pink blossoms wilted and green heart-shaped leaves dressed that tree.

Hubert adjusted the phone to his ear. Will talked of flights and restaurants and day trips he’d planned for them. “Yes. Yes,” Hubert said. He opened the construction file. He wanted the new glass room he’d designed for the doe to be a surprise for his son. It was almost complete. “Listen,” Hubert said, “why don’t you just come here? I’d love to have you, and you could meet her.”

“Meet who?”

Hubert pulled the drapes aside. Was she in the yard yet? The building crew had put up barriers to keep all wildlife off of the poured floor as it cured, but he knew she’d be curious.

“My doe,” he said.

Will laughed. “Well, listen, I’ll just have to meet your doe at Christmas because really, Dad, that’s why I was hoping you could get here. There’s no way I’ll be able to get away over Thanksgiving with work and stuff.”

“Okay, Professor! Get that semester buttoned up and I’ll see you soon enough.”

“Sounds good. Love you.”

“Love you, too.”

Hubert closed his laptop, stood next to the window searching the tree line for her. Outside he swept away the debris mud wasps had left on the battens, straightened his wood stack, the pinecone wreath on the door.

Miles McIntyre, Hubert’s closest neighbor, came down the drive.

“Your boy wanted me to check, make sure you don’t need anything,” Miles said. He stood in the middle of the yard, his hulking frame squeezed into his weathered game warden’s jacket, taking in the edges of the wooded lot, smoothing his beard and likely surveying the downed branches, the fallen black walnut’s trunk Hubert hadn’t gotten to yet. Maybe he was just remembering how much Genevieve, unlike Hubert, had loved collecting kindling, downed wood, or maybe he was remembering how she’d said, “I loathe their deaths but I do love how their loss opens up the canopy for others to grow, grow, grow.”

Hubert hadn’t joined them last fall. He’d stayed on the porch out of their way.

“He must have called you as soon as we hung up. Well, you can tell Will I’m just fine, Miles,” Hubert said. There wasn’t any movement in the trees.

“Will do,” Miles said, stepping from the porch.

“Yes, I am just fine,” Hubert muttered, rubbing at his brow. But he wasn’t. Two whitetail he’d noted in several trail-cam captures hadn’t appeared in three days: the twelve-point, part of a pre-rut bachelor group of four, and the little button buck that always grazed with Hubert’s doe. Simply disappeared. Hubert knew from the pamphlet Miles had given him a month before that archery season was in, so he straightened up his shoulders, tried to sound perfectly calm as he asked, “Did anyone around here tag a twelve-point?” He steeled himself for the answer. It had been Miles who’d warned him not to get too attached to the wildlife when he’d first expressed his desire to handfeed the herd.

“You’re only asking for trouble. They’ll want in your house.” Still Miles had explained the steps of earning trust, which foods to use, how to talk, walk, move around them. Of course, Miles didn’t know Hubert had fallen in love with one.

“Yep. Riley Bowser, Harold’s grandson, got a nice one. You’ve met Harold, right? Yeah, big twelve-point. Lung shot. Quick.” Hubert felt like air was being sucked from his lungs through some hole. “Put his picture in the paper, they did.”

“And any little button bucks?” Hubert couldn’t bear hearing it had been shot but he had to know. It always looked so skittish in the photos. So wary. Just like him. He was informed. He wasn’t naïve. He’d read the game commission’s harvest report Miles had given him, knew the numbers. Thousands killed each season, antlered and antlerless.

SERIOUS LIT

Every purchase helps keep our Appalachian magazine alive and thriving.

“Not sure about a button buck,” Miles said, kicking at the dried mud on his tires. “I’ll ask around. Usually archers go for the big racks, though. You sure you don’t need anything?”

“I’m sure.” Far off, the train from Echo to Brinie Furnace blew its crossing whistle, and high above a grey squirrel darted from one tall oak to another, sending acorns thudding to the ground.

“You okay, Hube?”

Hubert wiped his eyes with his handkerchief. This worry and crying would sometimes bubble up out of him with no warning. “Yes. These allergies. Molds. I think tree molds. They’re worse this fall, worse than I remember them from last.”

“Well, wet and hot summer. That’s what we get, I guess.”

“Yes, yes, it was.” Hubert blew his nose. “Oh, you mentioned before you could post safety zone signs, right? I think one of those Ramers has been walking through here.”

Miles took off his hat, pushed back his thinning hair, snugged it back on. “I don’t think you’ll have a problem, but, yeah, I can put some up later today.”

“I’d appreciate that.”

“Well, I gotta take off. Just call if you need anything, okay? And if you want help clearing the floor of these branches and such, say the word. Just got my saw sharpened.”

“I sure will. Thank you kindly, Miles.”

Miles saluted, a habit from when he was a Marine. He stopped. “You said the room’s gonna be all glass, huh? When are they putting up the walls?”

“They said they’d start first thing Monday.”

“It’ll go pretty quick from there.”

“I hope so,” Hubert said, fingering one of the cardboard boxes that held the glass wall panels. They’d been sitting on the porch since delivery a few days before. He was so anxious to have the room completed. Now even more so since hunting season had begun.

As soon as Miles pulled out, Hubert rushed to the house, to his computer. The local paper showed the smiling boy posing with the dead twelve-point, arrow threaded through its antlers, bow on the ground near one front hoof, quiver against its side, the boy’s gloved hands grasping the rack. Hubert closed his eyes. Breathe. Don’t get worked up. He had a porch to winterize. A shed to organize. Feed to scatter. He blew his nose again, shut his laptop.

His doe must have sensed his worry, much as he tried to push it away, for there she was by the shed waiting for him. Instead of slowly making his path to her, talking quietly, bridging the distance between them in a measured way, lest she leap and run, he yelled out, “You must stay close to the house. As close as you can.” Her ear twitched. She turned to look behind the shed and he ran to her. But she was like light itself, flying through the woods dodging saplings, stumps. A good fifty yards from him she stopped, turned around to look back, her markings slightly distinct from the last of the leaves.

“I’m sorry,” he shouted. “I, I didn’t mean to frighten you but I’m just so scared something is going to, to happen. Please just stay as close as you can.” She hesitated for a moment, then meandered farther and farther, camouflaged now completely by the trees. His eyes searched. Again, he thought of running to her, but he didn’t want to frighten her more. He didn’t want to tell her how his mind traveled to such horrible places where he pictured her zigzagged rush from the pain of a bullet or imagined her dropped in the berm, hit by a reckless driver, or found her bedded down in her favorite spot near Sidle Creek, but bleeding from multiple wounds, a spray of the shotgun—some pellets unable to penetrate her hide, others finding her heart and lungs and belly.

Movement. No. Not her. How he wished for a glimpse of her late summer coat, that ginger tone it had been when he’d first met her. But now her coat had changed to the color of wintered trees, a blueish tan that fall weather and a needed cover for survival had made her.

There. There she was now. He squinted. There. Blending completely but for the white rings around her eyes and muzzle.

And then, gone again.

He bit his lip as he struggled to remove the thick plastic from the mineral block. He carried it to the small stand, his head thumping to its edges with dread. He dipped the coffee can into the large bag of shucked corn. Sprinkled the yellow around the mineral block. He waited outside the shed for over an hour for her return, but not one deer came in to feed.