There is another Appalachia, just as gritty as ours but across of the Mason-Dixon line. Anna Lea Jancewicz was born and half-raised there. With this stirring essay, she describes a landscape that might seem familiar to Southern mountaineers—a rolling blue horizon and wild huckleberries growing alongside railroad tracks—but a different set of immigrants shaped this place. Onion-domed churches abut the coal mines in this part of Appalachia, and pierohis are on the menu.

Today, Anna Lea lives in Norfolk, Virginia, where she homeschools her children and haunts the public libraries. She is an editor for Cease, Cows and her writing has appeared or is forthcoming at Necessary Fiction, Phantom Drift, Split Lip, Sundog Lit, and many other venues. Her flash fiction "Marriage" was chosen for The Best Small Fictions 2015.

Also, she assures people that, yes, they can pronounce her last name Jancewicz: Yahnt-SEV-ich. Go ahead give it a try, and leave a comment letting us know what you think about this piece, our first ever dispatch from the Appalachian North.

*

Yeah, everybody has a dead grandmother story. They’re not sexy and nobody’s buying. But this story is mine, and it’s not so much about the woman as it is about the place. I’m from a little coal town, McAdoo, in Northeastern Pennsylvania. A place where people still use clotheslines, and it has nothing to do with being green. A place where weddings and family reunions mean at least a fist fight, and maybe one of Aunt Vera’s boys pissing in somebody’s car to teach them a lesson. A place where it’s hard to say whose sin will draw the nastiest whispers, the cousin who’s suspected of covert abortions, or the cousin who had the gall to earn a PhD. A place where aunts will still recommend spiking a baby’s bottle with Karo syrup, and stare slack jawed when you reveal that all of your children made it through infancy without ever touching lips to a rubber nipple. A place where a cousin can snarl about all the illegal Puerto Ricans and not understand why you burst into laughter and shake your head. A place where uncles capture snakes from inside houses in paper grocery sacks, where a black bear might just amble out of the strippins, where great-grandfathers sit with Phillies baseball games on their transistor radios eating tomato and oleo sandwiches before they die of black lung and are buried in their Knights of Columbus uniforms, swords by their sides. A place where Grannies yell at kids in words that are not English, and the onion domes of Byzantine churches rise once-resplendent in once-golden paint above streets crammed with clapboard houses and American flags.

Because this is Appalachia, but this isn’t the Appalachia you think of, with bluegrass and cornbread and kids named Billy Bob. This is where kids are named Stanley, and you can’t pronounce their last names, what with the sz’s and cz’s and w’s that sound like v’s. And the Stanleys all say youse guys. This is the Appalachia where grandmothers don’t flinch to say cocksucker in front of you when you’re little enough to only picture an awkward situation for a chicken, but Protestant is whispered, a dirty word. This is the Appalachia where you vacation Down The Shore, and peppers are mangos and you sit on your dupa and shut your trap for two-tree minutes now, henna?

The colossal maw of an abandoned strip mine yawned behind my grandparents’ house, the house that my Poppop built himself, just down the big back lawn and across the alley from the looming house that he was born in, the house that my Granny and Grandpap lived in until they died, where Granny’s parents had been laid out for their home-funerals, back when such a thing was what was done. My second cousins lived in one half of that house, and the youngest was just my age. The summer they finally paved that alley, she and I got in a fight, each of us on either side of the cooling asphalt, and one of us hit the other in the forehead with a well-pitched rock. I can never remember which one of us threw the rock and which one of us bled. We were that close. When she got knocked up at fifteen, I thought Well hell, I can’t judge. There but for the grace of God and my parents’ trusty pick-up truck go I.

Because my mom and dad got out, had packed up everything we owned and moved us, pick-up truckload by pick-up truckload, to Virginia in 1979. I was four. The world had been all of a couple miles squared, and every person I’d ever seen had known my name, known my family. I’d thought black people were only on TV. But you’ve heard the Billy Joel song, so you know that part of the story. The coal was gone, the factories were closing. “It’s getting very hard to stay…”

But back I came, each summer wowed by the horizon appliquéd with ghosty blue silhouettes of mountain tops, back to this place that seemed on one hand bursting with magic and wildness, and on the other just plain backward. Down at the bottom of Logan Street, behind Poppop’s house, there was the Shit Crick, into which all the borough’s raw sewage was emptied. There were no big box stores, no fast food restaurants. We’d get on the highway in Poppop’s big green Oldsmobile, cruise-control it to the Frackville Mall for that. I’d perch on the armrest beside my grandfather as he sang Sinatra, keeping my eyes peeled to catch sight of the golden arches high atop the hill as the mall came into view. Or we’d wind down the mountain to Walt’s Drive-In for soft serve ice cream cones, watch golfers on the driving range behind, bring back a CMP sundae for Nanny. Her favorite, chocolate/marsh mellow/peanuts. What McAdoo had was the firehouse, with booze at night. An Italian place, for pitza, the kind that drips orange grease to bleed through stacked paper plates and needs to be folded in half to fit in your mouth. An inexpertly hand-painted sign nailed up crookedly outside somebody’s door, advertising ETHNIC FOOD, and that means pierohi, halupki, halushki. There was a roller rink, but that was closed down every summer, or maybe just closed down for good.

My cousin and I roamed, played all the make-believe games. We watched Hatchy Milatchy on black and white TV, and put on dance shows for Aunt Peggy when she came home from working at the Kmart in Hazelton, and dressed up in Granny Palmer’s old handmade floor-length slips and her other accessories, antique handbags and scarves, that my Nanny still had saved in a trunk. We picked Queen Anne’s Lace and put the flowers in glasses of water and food coloring, watched the blooms turn colors. We argued over which celebrities we’d marry, we argued over which of her teenage sisters’ boyfriends was the cutest, and when we got a little older we’d skulk in alleys and sneak cigarettes and sing Guns N’ Roses.

These were my summers, until Nanny got sick.

***

It’s a few days after my fourteenth birthday, and I’m standing in the December rain, straddling one of my cousins’ old ten speed bikes, watching some strangers dump backhoe shovelfuls of cold wet dirt on top of my grandmother’s coffin. Nanny is down in that hole, not wearing the colorful polyester pantsuit she asked to be buried in. She’s wearing the mint green gown that she wore for one of the twins’ weddings. They said what she wanted was tacky. I went back to the house with everybody else after the funeral, but they were all eating and talking, and I didn’t feel like doing either. I came back, by myself, to watch this.

There are several acres of cemetery out here on the edge of town, butting up to the railroad tracks, before you cross over to the long road through the woods where wild huckleberries grow in summer, where cold, cold water bubbles up from mountain springs, the road that leads out past the cigar factory, over to Tresckow, where both my aunts live. Chain link and crumbling stone walls separate sundry graveyards that belong to different churches, fences that keep the dead Poles from the dead Italians, the dead Irish from the dead Slovaks, the dead Rusyns from the dead Hungarians. I look out and see a wide expanse of granite headstones jutting from the variegated drab greens, browns, yellows of grass that’s been frostbitten. Looking back toward town, I see the sloping streets crowded with clapboard houses, and the squalid onion spire of St. Mary’s against the low gray clouds.

***

She hadn’t been my favorite. My Poppop was dedicated to spoiling me, sneaking me sugary cereals in tiny boxes and buying me cheap toys at the IGA. She was dedicated to tough love, making me spend the whole summer writing out my multiplication tables, and telling me that wearing those tight jeans like my cousin did would give me crotch-rot. But then she got sick. Really sick. She had at least two kinds of cancer at the start, one of which required bed rest, the other of which was best managed with an active lifestyle. We would walk two miles every morning, in a big loop, very slowly, very carefully, and then she would spend the afternoon in her reclining chair. I spent a lot of time with her. We talked a lot, like we never had before.

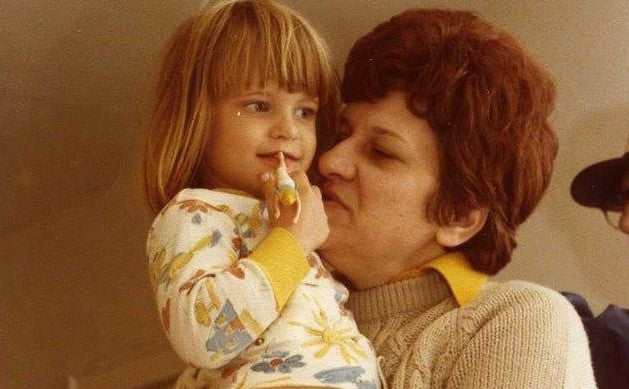

She told me stories. Her toes curled up girlishly, and she rubbed her feet together as she told them. Stories about drinking fresh hot milk from the goats her parents had kept in their yard over on Jackson Street. Stories about her father Wasyl coming to America from Russia, how the coal company owned him, how he never really learned English. Stories about dating my grandfather, illustrated by black and white photos held into the albums with those little paste-on corner frames; pictures of Poppop with slicked-back hair, in white tee shirts and blue jeans, looking like Marlon Brando, her by his side in bobby socks, the captions calling her Katie when I’d never heard anybody call her anything but Kathleen or maybe a few times Kathy. Stories about my mother when she was little, about how she finally got so tired of washing and brushing and ironing my mother’s hair that she one day surprised her by lopping it off with a sly pair of scissors after her bath; about how she got so sick of my mother sneaking out of the house with her bell-bottom jeans rolled up beneath her school skirt, those hippie jeans embroidered with a big pair of hands grabbing the ass cheeks, that she stole them and burned them in the furnace. Stories about nursing school, working at the hospital, traveling on her cruises. The story of when I was born, two months early, tiny but strong, and she was there in her crisp white uniform to assist Dr. Lee with the delivery.

But most of all, she liked to tell me about her favorite movie.

I’d never seen it, The Sound of Music. We never watched it together. It was the mid 1980’s of course, and my grandmother didn’t own a VCR. The idea of popping a tape in and watching a movie whenever you wanted to was still an absurd exoticism. But this was even better. She recalled the plot for me a thousand times over. She described the characters, recited dialogue, sang the songs. I felt like I knew the whole movie by heart. It made her so happy, even when she was exhausted and struggling, even when she was so bent that she couldn’t lie in the bed anymore and had to spend all her time in that brown reclining chair. She died in that chair.

We’d come up to visit for Christmas. My birthday is the day after. I heard her the night before, up all night with my mother by her side, begging my mother to help her kill herself. Asking for her sewing scissors, as if she’d be able to do the job with them. She told my mother that she could see her parents, standing in the hallway outside her bedroom door, waiting for her. Then in the morning, on the day I turned fourteen, she took one last gurgling, labored breath. She was 54 years old.

***

The rain has soaked through my clothes and I am freezing. The grave is filled and I’m alone here, the workmen are gone and it’s getting dark. I pedal back up to the Slovak church, and I slip inside. The doors have never been locked, day or night, any time I’ve tried them. That would never happen in the city where I live. But I’ve come here a lot, this is familiar. I kneel in front of the painted plaster Blessed Mother in the dim and quiet. Her eyes are like anthracite slag. I light one of the votive candles, add one more flickering flame to the field of squat red glass cylinders. I reach deep down into the pocket of my jeans, and I pull out my rosary beads.

***

I’m sure I’ve been gone a long time, but nobody seems to have noticed. Most of my relatives have gotten pretty drunk, even the ones for which it takes a hell of a lot. As I walk in, I hear an aunt say She held out for Christmas, she held out so she wouldn’t ruin Christmas for everybody. My Poppop turns his head slowly, slurs, one thick finger pointed at my chest, She died on your birthday, so you can never forget her.

I change into warm, dry clothes. I ghost past them, between them, eat a little frosting from my cake; it’s still in the fridge, pristine, with the plastic ballerina on top. I go into my grandmother’s bedroom; nobody wants to be in there. I shut the door and curl up in the dark, in her chair. My hair is still damp. I’m remembering when I was scared to sleep in the dark, in this room, and she told me The dark is nothing to be afraid of. God made the dark so that every body and every thing can rest.

I’m sobbing now, choking and heaving.

And when I’m done, I breathe deeply. I rub the brown velour upholstery on the arms of her chair. I notice the remote control for the television on her bedside table, just where she must have left it last. It’s barely visible in the dark, but it somehow catches my eye. I sigh, and I pick it up. My finger touches the power button, and there it is. In Technicolor. Julie Andrews, twirling around and around and around:

“The hills are alive with the sound of music,

With songs they have sung for a thousand years…”

***

My grandmother left me her wedding ring when she died, she left it to me. My mother took it, said I couldn’t be trusted with it yet. My mother wore it on her own finger, for years. As my birthday approached, in 2004, she asked me if I wanted anything special for turning thirty. Yeah I said I want Nanny’s ring. She gave it up reluctantly, but now I wear it. It reminds me of where I’m from.

When people asked, I used to say Oh, from around Allentown. Or maybe Do you know where Scranton is? Wilkes-Barre? But those answers are not quite true. So, you ask me now, ask me where I’m from. I’ll look at my finger, and I’ll tell you:

Yeah, everybody has a dead grandmother story. They’re not sexy and nobody’s buying. But this story is mine, and it’s not so much about the woman as it is about the place. I’m from a little coal town, McAdoo…