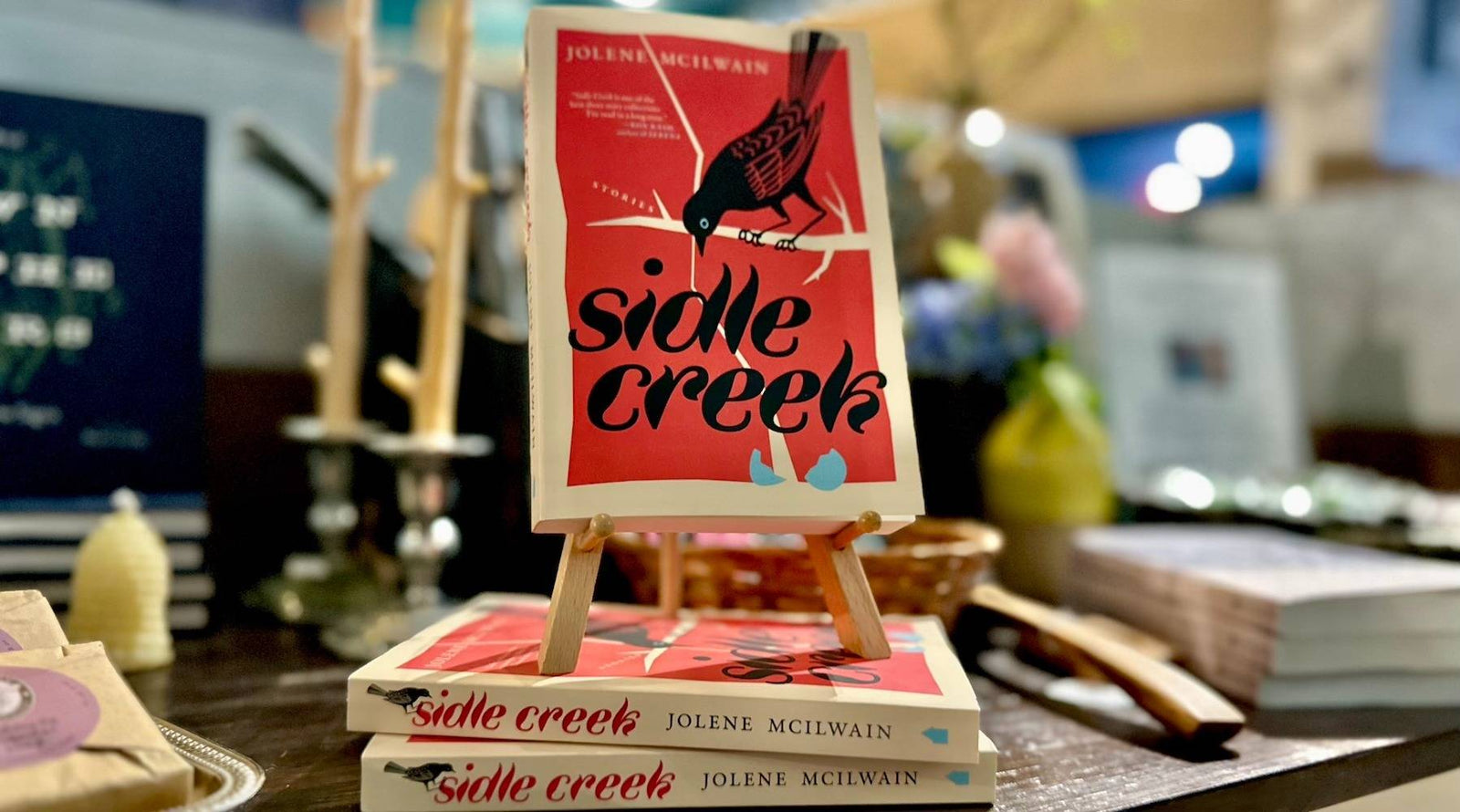

MASON BERNARD HORTON IN A W.VA. MINE. PHOTO PROVIDED BY HIS FAMILY.

“Coal is how our ancestors survived and thrived in these mountains.”

— Megan Brown, The Pretty Pickle

In most stories about West Virginia, Big Coal is depicted as a blood-thirsty villain intent on decimating mountaintops and turning miners’ lungs to ash. But Megan Brown knows coal differently.

“Despite the contemporary perception of coal as toxic, dirty, and negative, West Virginians cherish it as a symbol of opportunity,” said Megan, a Mountain State native and descendant of miners. “Coal is a legacy that benefited our ancestors and continues to empower hardworking men and women today.”

Raised in Fairmont, West Virginia, Megan grew up listening to stories about how her paternal great-grandfather, Mason “Bernard” Horton, pulled himself out of poverty by working for the Jamison Coal and Coke Company in Barrackville.

“He and my great-grandmother, Eva Lillian Ridgeway Horton, lived for a brief time in the coal camps,” Megan said.

But it wasn’t long before Bernard climbed the company ladder, assumed the position of crew shift boss, and purchased a home in town. “He was able to rise to the middle class by mining,” Megan said proudly.

Megan’s 95-year-old grandmother, Dorothy Horton Haugh, still remembers watching her father walk home after a long shift in the mines.

Whenever he reached the baseball diamond behind their house, she and her two sisters, Cora and Ann, would run as fast as they could. Whichever daughter greeted him first got to munch the leftovers in his lunch pail. Some days, it was a hunk of salty ham. Other days, a slice of stale bread.

“But no pepperoni rolls,” Dorothy said, referring to the uniquely West Virginian snack of dinner rolls stuffed with cured meats. “Those came later with the Italian immigrants.”

Sometimes, though, Dorothy wasn’t sure if her father was ever coming home. When she was seven years old, for instance, a fire broke out in the shaft of Bethlehem Mine No. 41. It was May 12, 1935.

Though Bernard worked for a different company, “Barrackville was a very small town, so the men in any mines would have all known each other,” Megan said.

Determined to save his brethren, Bernard spent that spring night pulling men from the white-hot inferno. According to a newspaper article, the fire was so “spectacular” that it shot flames 500 feet into the air.

Five miners burned to death that evening. But if this tragedy gave Bernard pause, he didn’t show it. The next day, he strapped on his boots and headed back underground. He had a family to provide for, after all.

“Coal mining served as a vital pathway for the working class,” Megan confirmed. “Coal is how our ancestors survived and thrived in these mountains.”

MORE FROM THE PRETTY PICKLE

To honor this legacy, Megan sells a coal dust pendant necklace through her jewelry business, The Pretty Pickle.

Eye-catching yet subdued, the bronze bezel features bits of coal dust embedded in a jewelry-grade epoxy resin.

“The coal I’m using right now comes from my parent’s neighbor, who is a retired miner,” Megan said. “I also pick up coal from along the train tracks in front of our house.”

Though Megan has been a public school teacher by trade, jewelry came into her life about a decade ago when her father suggested she experiment with encasing pressed flowers in epoxy resin.

“I never looked back,” said Megan, who soon started making necklaces and earrings using mustard seeds, Queen Anne’s lace, wings from naturally deceased moths, marigold petals, and other foraged materials — including coal. She founded her company in 2010 and stepped away from teaching about eight years later.

According to Megan, the business name — The Pretty Pickle — nods to her childhood tendency to drink jars of salty pickle juice at lunchtime. Her elementary school friends nicknamed her “Pickle” because of it.

“No one calls me that anymore,” Megan said, chuckling. “But I do love alliterations and making pretty things.”

She also thinks of her artistry as a type of pickling. Sure, there’s no white vinegar or canning salt involved. But just as someone might preserve a bushel of farm-fresh cucumbers, Megan is preserving everything from fern fronds to hibiscus tea leaves.

Her jewelry also preserves the legacy of coal mining.

“Everyone who has roots in West Virginia also has roots in coal,” Megan said. “It is imperative to pay homage to those roots and acknowledge the significance of our shared past.”