This is a girl on the run. And author Robert Gipe has given her good reason. In his debut novel Trampoline (iTunes/Amazon), Dawn is surrounded by drug addicts and a decimated landscape, a horrible version of Appalachia that she wants to escape and the rest of us hardly want to see.

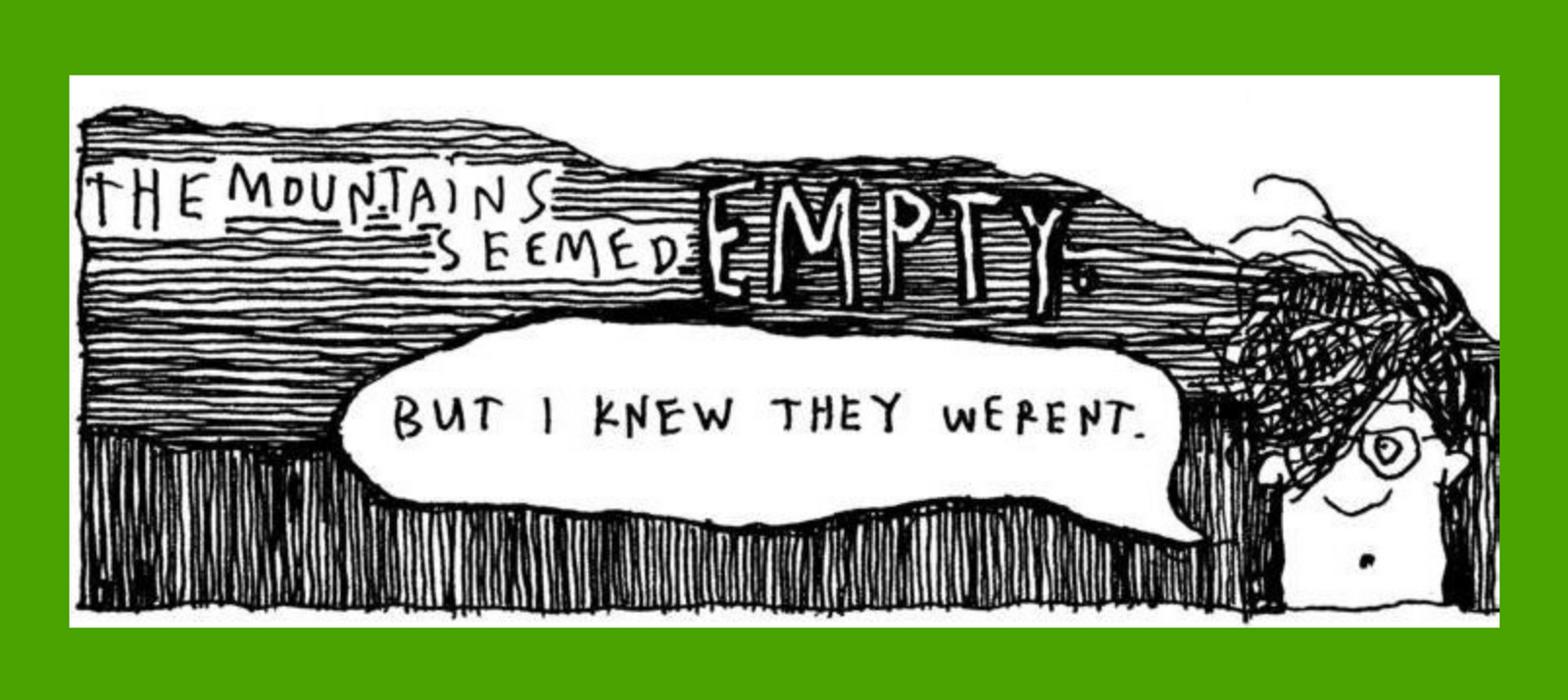

Me included. Ohio University Press sent a review copy of the novel over a year ago, and I fell in love with the book's teen protagonist and Gipe's goofy illustrations of her internal life. The writing is remarkable—clean, true to place, and at times breathtaking, like this advice from Dawn's grandfather.

Fear men. Flee them. Give them nothing. They mean you ill. Their voices smack of honey and their words set off string music in the chambers of your heart. But mark my words: they will cut you down, chop you up, cook you over fire, eat only the pieces that suit them, and throw the best of you into the weeds for other beasts to rend and gnaw.

Pretty, ain't it? But also brutal. Men can be awful in this book. Dawn's brother Albert only shows at school to deal drugs. Her uncle forces her to tend his moonshine still. And the women aren't much better. Wasted girl cousins and girlfriends of boy cousins litter so many collapsing trailers, while lost in grief, Dawn's mother has given up on everything but the bottle.

"I was a freak, soft and four-eyed," Dawn says, describing herself and her kin, "with black fingernail polish, a dead daddy, a drunk mama, a crackhead brother, outlaw uncles, and divorced grandparents who made trouble for normal people every time they come off the ridge."

Without flinching, Gipe shows just how awful Appalachia can be, and that's why it took a year to write this. He made me think about ugliness in my own family—the cousin who turned tricks to buy drugs, the aunt who was thrown from a balcony during a drunken brawl, people I love who've lived under bridges, and all the children who've been taken by Social Services. There are a lot of them, and most days, I'd rather opine on the latest farm to table restaurant than ponder where they ended up or, even worse, how they'd turned out if they'd stayed in my family.

Still, I finished Trampoline. In fact, I couldn't put it down. Gipe kept me glued to his book by matching every ounce of blunt dysfunction with an equal amount of elusive delight. Yes, there is violence and anger and just plain meanness in his Appalachia, but there is also beauty and insight and subtlety.

Take Dawn's aunt. Named June, she fled across the border to Kingsport, Tennessee decades ago, putting miles between herself and all the roughness back home. When Dawn visits, another side of Appalachia is revealed.

June's front room was dark and golden, like a pirate cave. There were posters on the walls for hippie music shows and works of art that were funky and done, you could tell, by people June knew. There were quilted and woven and crocheted things, and it was hard to imagine anybody ever throwing up on any of it or anybody ever flinging a chair at somebody in that room.

While it enlarges the book's universe, this excerpt alone is still a gross simplification of what Gipe has created. It would have been easy to pit Appalachia's haves and have-nots against one another—God knows plenty of writers do—but Gipe is more sophisticated. Let's stick with Aunt June as an example. Of late, she has come to miss exactly what she tried to escape when she moved to Tennessee and built a self-described fortress of solitude. "I miss all the racket people made when they got together," she tells Dawn, "everybody talking at once. Everybody jammed up together on the porch or in the front room, the kids all keyed up."

This lovely twist is one of dozens that kept me guessing. Every time I thought I had Trampoline figured out, Gipe ran against the current, creating some eddy that delighted me, that made his world intoxicating and supremely real, as complex as any life off the page.

My favorite surprise is Dawn's intense, almost preternatural, relationship with the mountains. On and off, she imagines them before Europeans settled, before their descendants trashed the land, an inner monologue that reveals how profound a fifteen-year-old can be. She fantasizes about buffalo retaking Appalachian valleys and asks what the Cherokee and Shawnee thought when forests were clear cut. To them, she figures, a farmer's field would have looked no better than a car wash.

Here, she tells how the mountains keep her sane.

The trees and the roll of the earth held me up like the ridge holds the clouds from passing so it can pour down rain. The vines and rabbits and the squirrels and the orange lizards out on the rocks after a storm—all those things I'd forget when people dragged me down—I needed them close and always, where I could get to them quick when Albert was crazy on some new dope, when Momma was out of her head, when Mamaw pulled back into her groundhog hole of nothing for me, when Hubert made me want to blow his head clean off—there was only the mountains could talk sense to me.

If nothing else connects mountain readers to this book, this should do it. Whether you're the child of a coal barren or cooking meth in a shed, you see the same fog-laden hollers; the same blue peaks define your sky. Landscape is our equalizer. It inspires and constrains us all, providing an awesome stage where we love deeply and go mad, where we till the earth and meditate, where we craft stories, like this one, which is such a brutal, gorgeous force, so steeped in local culture, I do wonder if it is the most Appalachian novel ever.