"I wanted to create a really different environment, a world made by hand; the Appalachian mountains were full of people doing just that," she told me in a recent interview. "For a young woman from Winter Park, Florida, it felt like a foreign country!"

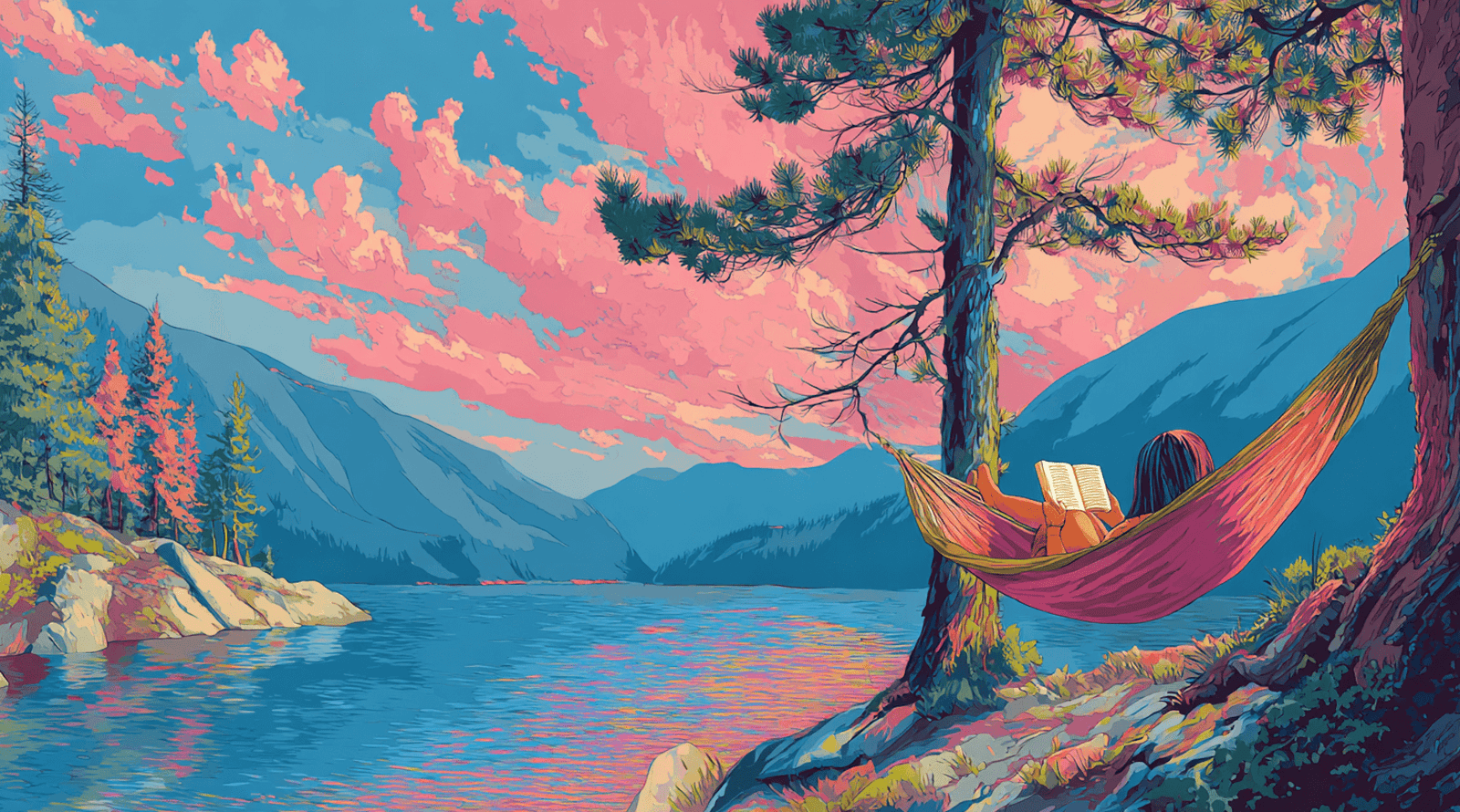

[caption id="attachment_9164" align="alignright" width="249"]

"My Boulders" by Karen Tunnell.[/caption]

"My Boulders" by Karen Tunnell.[/caption]Working as a traveling Head Start teacher, Karen visited families on hills and in hollers across Western North Carolina, and the one piece of art that she saw in nearly every home was a quilt.

"I'll never forget Jersey Cook," she said, "a neighbor in Little Laurel community, whose tiny cabin was full of dozens of unfinished quilt tops, all pieced by hand and smoky-smelling from years of her cooking on a wood stove."

At a time when many people still dismissed quilting as an old lady craft, Karen recognized the artistry in these pieces. She began to study under women like Jersey, joining quilters in their homes and around quilt frames that lowered from ceilings in little church meeting halls.

"As many artists do, I started by studying the foundations and history of my chosen media—both painting and quilting."

Over time the two disciplines merged, revealing a new media that has won Karen worldwide recognition. She calls it "quilted painting," and as you'll learn in the below interview, it has led her to push the boundaries of what a quilt can mean.

*

TR: Karen, thanks for taking time to talk with me. When I saw your beautiful work, the first question that came to mind was "does she use these?" If we came to your house today, would we find one of these art pieces on your bed?

KT: My first quilts were for beds, hand sewn using ancient paper patterns. After 45 years I still love hand work, but most of my pieces now are more like paintings than quilts and always hang in a frame on the wall.

TR: Now your quilting started in the North Carolina mountains. What attracted you to the area and do you still go back there?

KT: Going from the Atlanta College of Art to quilting bees in Madison County, North Carolina was a dramatic move in the early 70s. Along with many others of my generation I was seeking a simpler, wholesome life in the mountains, so I happily embraced traditional quilting along with farming, cooking on a wood stove, and folk music.

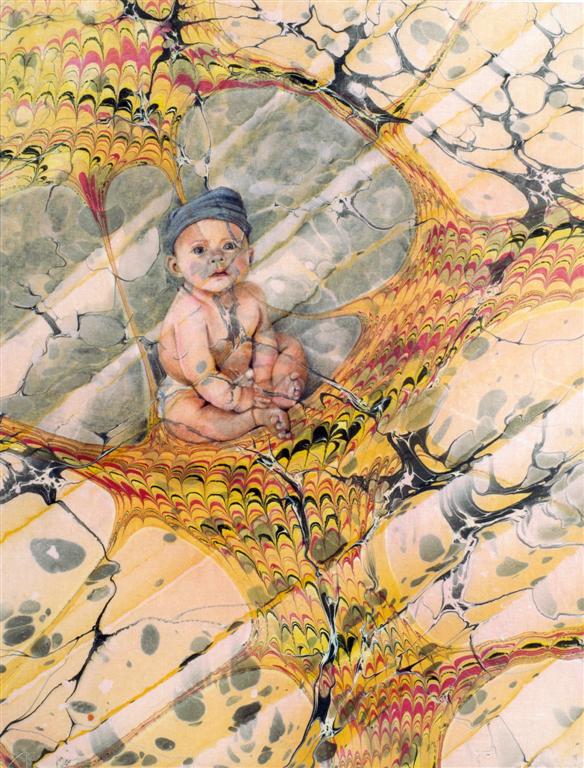

[caption id="attachment_9168" align="alignleft" width="245"]

"Turban Baby" by Karen Tunnell.[/caption]

"Turban Baby" by Karen Tunnell.[/caption]While I have an electric stove now, what hasn't changed is my love of the southern mountains. I have a home in Midtown Atlanta and one on Lake Santeetlah in Graham County, North Carolina, where spectacular views continue to inspire most of my quilted landscapes.

TR: Over time, your work began to focus on environmental themes, which I think is enthralling. I've never heard of a quilter tackling big social issues before. How did that come about?

KT: In 2010, as the BP oil spill disaster was unfolding in the Gulf, I was in my studio experimenting with a hydro-printing technique called "spanish wave," which creates the illusion of a 3-D, turbulent surface on flat fabric. What came out of the tray that week was a collection of prints eerily reminiscent of oil on water. As a result, I began a series of pieces depicting birds, plants, and sea life affected by our sometimes disastrous quest for fossil fuel. This series of about 25 pieces I called "Oil on Water."

TR: Wow, 25 pieces. That's a huge collection and a big change in direction. Where did you go from there?

KT: At the same time I began to long for my first grandchild and found myself drawing peaceful little babies on fabric backgrounds that to me appeared polluted and threatening.

And back in the mountains, it was impossible to ignore the devastation of non-native insects, like the woolly adelgid on our hemlocks and firs. Coal-fired power plants contribute acid rain to the toxic mix.

As I drove through the Smoky Mountains National Park one day, I had a through-the-windshield view of miles of dead and dying conifers. My latest series, "Ghost Trees" tells this story in long panoramas of bare, bleached trunks.

TR: You've done so many beautiful pieces, some carrying deep meaning, others, like your kaleidoscope patterns, containing beautiful shapes. Which one makes you the most proud?

KT: Although my "environmental angst" seems to crop up in all my landscapes, whether I welcome it or not, this is the work I'm most proud of, especially pieces like "Ghost Trees" that convey the dual message of extraordinary natural beauty and the threat that we ourselves pose to its survival.

TR: Your work, of course, has already been displayed in galleries and exhibits around the world. If you could show anywhere new, where would it be?

KT: If I could display my work anywhere in the world, I would choose a museum of natural history over an art museum. I've had a few opportunities to do this and would like more. To reach a new audience, especially a young one, with art created to praise this world's beauty and challenge us all to preserve it.