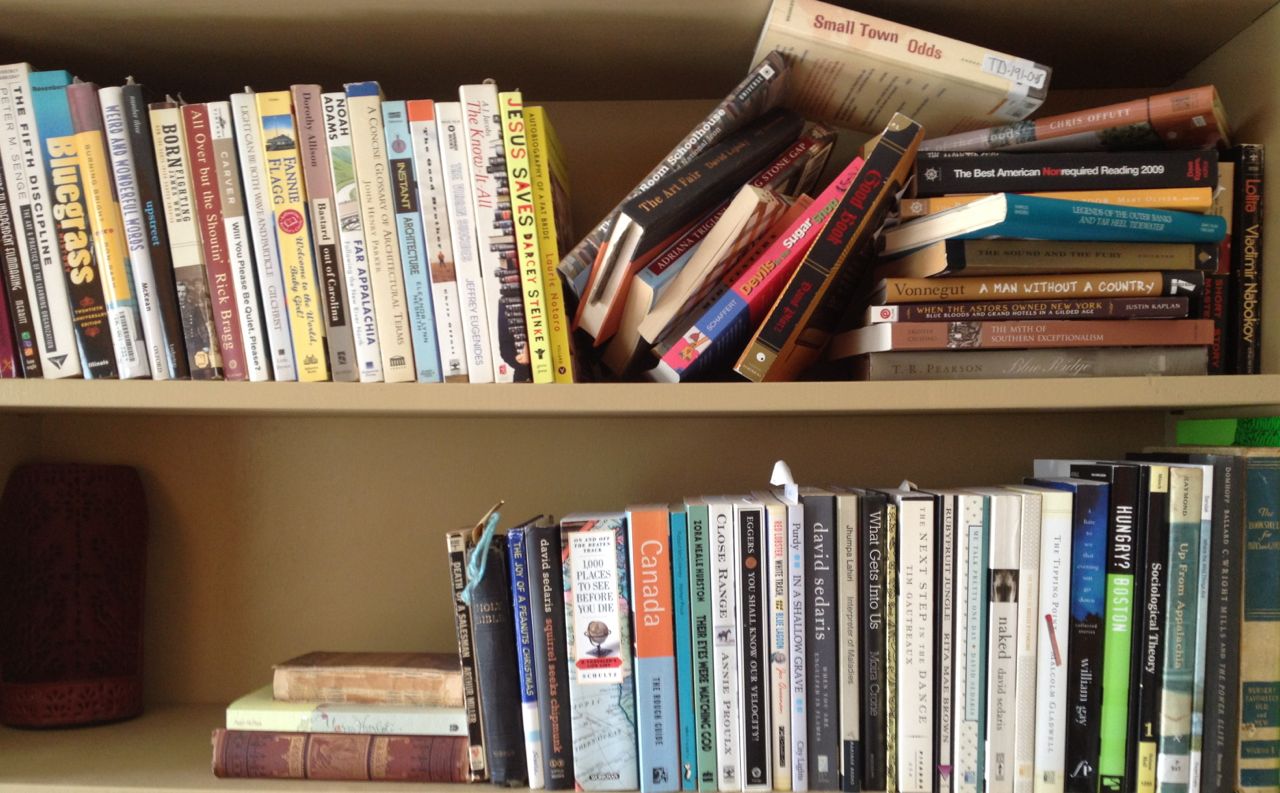

On one side of one shelf, though, there's this mad jumble. This is the book pile. It consists of books I’ve not yet read. Some lie on their backs. Half are on their sides. Others are wedged in at awkward angles. It looks like they’re climbing overtop one another, trying to get my attention, clambering for the top.

This mess is not my fault. I swear. I’ve arranged the book pile many times, but somehow, it keeps ending up this way. Over the course of years, I have come to accept the one plausible explanation. I figured I was coocoo for thinking it at first, but now I know that this must be the truth:

My book pile is a sentient creature.

Before you close this post and delete all links to my blog, hear me out. I’ve not come to believe this just because of the spontaneous messes. Making those is not all the book pile does. It also picks out books for me, and it’s not indiscriminate about it. Whenever I’m ready to read something new, it’s like the book pile has already gauged my mood or emotions or life path or something, because the right book is always there on top, just like it has been hand picked and launched up at some crazy angle—one that is so eye catching, so unlike the rest of the clutter, I can’t miss it.

This has happened dozens, maybe hundreds of times now, and each time the book pile has been dead-on. Most recently, it surfaced two impossibly similar books. Both were young adult novels. Both had Appalachian themes. One was about a girl. The other was about a boy. They caught my eye back to back and turned out to be perfect compliments to one another.

The first, Child of the Mountains, was a suspenseful slice of mountain life, filled with the energy of a girl edging into adolescence under desperate conditions. The second, Jim the Boy, is quieter; the writing has an elegant simplicity. It is built around the truths that are found in country living and the common circumstances that turn a boy into a man.

Tell me that's a coincidence.

These stories are like matching bookends—some kind of literary set sent to me by the Great Book Pile, which warrants capitalization for it is now my guru, my swami, my sage.

Be warned. I’m recruiting converts. After reading today’s review of Child of the Mountains and the upcoming one on Jim the Boy, you might find yourself making a pilgrimage to my shelves and chanting right alongside me - “All hail The Great Book Pile!”

*

Child of the Mountains

When we meet Lydia Hawkins, she has been torn from Paradise, the aptly named hollow she calls home. There she churned apple butter with her beloved granny, played with her precocious younger brother BJ, and traded hugs with her loving momma. That is, until her whole world fell apart.

When we meet Lydia Hawkins, she has been torn from Paradise, the aptly named hollow she calls home. There she churned apple butter with her beloved granny, played with her precocious younger brother BJ, and traded hugs with her loving momma. That is, until her whole world fell apart.Lydia is on her own now. Her granny and BJ have both passed, and while her momma is alive, she is imprisoned, serving time for a crime she didn’t commit.

Lydia proves to be a pragmatic girl. She tries to make the best of things. She ignores bullies at school and steers clear of the aunt and uncle who have taken her in, observing that these relatives “ain’t got nary a clue about what to do with me.”

She's right. They treat her more like a boarder than a bereft child, so Lydia learns that she has to make it on her own, sometimes taking her independence to extremes. For instance, while Lydia is alone “the way of women” comes upon her. It's her first period, and she does not call for her aunt or seek help from any other woman. Her momma told her that this would happen before she was shipped off to prison, so Lydia takes matters into her own hands. She finds an old rag and safety pins. She hides in the bathroom, and she fashions a maxi-pad.

I'll admit it; I was taken aback when I read this scene. It's not because I'm squeamish about menstruation. I was raised around too many women for that. This is a transformative moment in a young woman's life, and I'm glad it's in the book. When I saw how Lydia handled it, though, I kept thinking man, this is one hardcore little girl!

As the book progressed, I was relieved to see that the main character is not all pluck and fortitude. She does feel overwhelmed by her horrific circumstances. She gets down. She is full of self-doubt. I like this. It makes Lydia more dynamic. It gives me, the reader, a chance to identify with her loneliness and worry, not just admire her bravery. When she asks God to send her baby brother back because she’d rather he be a ghost haunting her than just be dead, I hurt for Lydia. I want to reach into the book and hug this child who has lost so much.

We see pleas like this with complete clarity, because the author, Marilyn Sue Shank, has employed a common device. She has written each chapter as a journal entry from her protagonist. In lesser hands, this can become trite, over-emphasizing a character’s whims and weighing down the story’s action. Shank, however, keeps her plot moving. She starts with two great hooks—a girl trying to fend for her self and the mystery surrounding her mother’s incarceration—and she uses them to advances the storyline in every single chapter.

That's impressive, but what distinguishes Shank's book is its local flavor. Child of the Mountain is not just a young adult novel; it is also a study in Appalachian culture. Shank has crafted lovely descriptions of the land, and she has written Lydia with a distinct mountain accent. Through most of the novel, this is a delight—reading the twang and idioms that define our region, seeing a well-rounded character cut from the same cloth as the people I love—but at points, Lydia’s language becomes so archaic it verges on the unbelievable. The book is set in the 1950’s after all, the era of jet travel and frozen dinners. I question whether a preteen girl—even one who was raised in a secluded hollow and influenced by a grandmother who would have been born at the turn of the century—would use words like “nary” and “iffen.”

This reflects my one complaint about the book. Shank does a great job of showcasing mountain culture, but she does so bluntly. Lydia has well-formed opinions about unions and mine pay for a girl her age. Her granny touts the benefits of sassafras tea like she’s selling it. And her teacher, in the midst of an otherwise intimate conversation with Lydia, gets downright didactic when he explains the relationship between Appalachian English and Old English:

“Did you know Shakespeare loved to write double and even triple negatives? He used multiple negatives to emphasize a point, just as mountain people continue to do today…Mountain people are not ignorant. They’re merely using a way of speaking that other English-speaking cultures have forgotten.”

Could this be more artfully delivered?

Sure. But Lord forgive me, because I shouldn't be complaining. This book is a gem. I mean, how often do you see such reverence for mountain people?

Child of the Mountains is a solid novel that does more than entertain. It connects young readers to the Appalachian South. The ones who hail from elsewhere will learn to respect the region, and natives will swell with pride when they read it. The book reminds them that their hills and hollers aren't common. Like Lydia, they live someplace special.