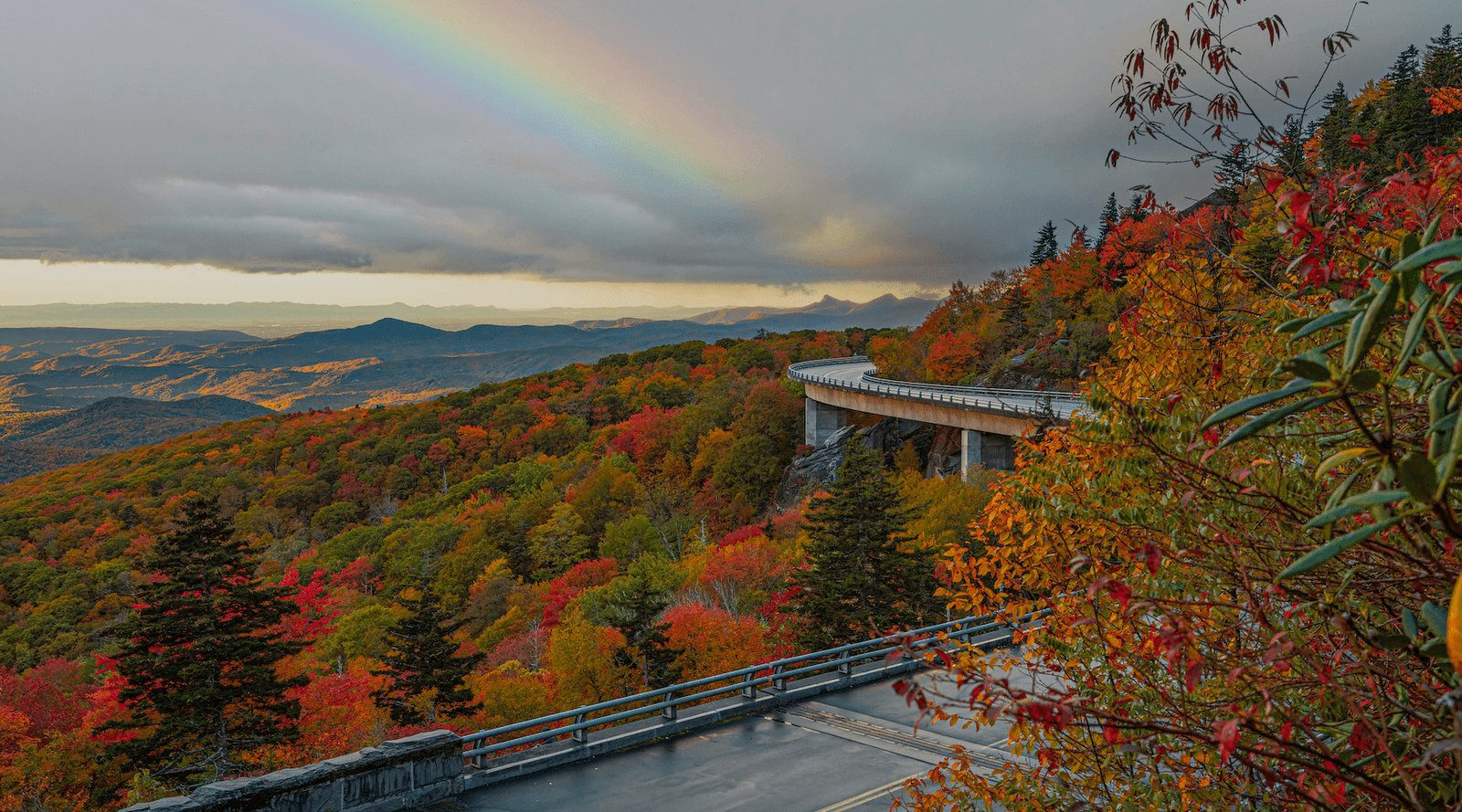

MONARCH BUTTERFLY AT MILKWEED MEADOWS FARM. PHOTO BY KIM BAILEY.

"If you have a yard,

you can help butterflies in five easy steps."

Kim Bailey calls herself a chef. But you’d be hard-pressed to find her fretting over parmesan risotto or herb-crusted ribeye. Heck, most days you’d be hard-pressed to find her anywhere near a kitchen. That’s because Kim makes her living cooking for insects, not people.

“I’m a pollinator chef,” Kim clarified from a field in Fruitland, North Carolina, about 30 minutes south of Asheville. It’s here, on Clear Creek’s grassy bottom-land that Kim and her husband, Jeff, produce a “bountiful buffet of plants” at Milkweed Meadows Farm. Their pollinator smorgasbord attracts swarms of butterflies from painted ladies to Appalachian tiger swallowtails to red admirals to what may be North America’s most beloved species — monarchs.

“This year, a female monarch showed up at the farm on April 6 and laid eggs on swamp milkweed that was just barely coming up,” Kim said excitedly, noting that the butterflies also enjoy blue mistflower. “I’ve counted up to 80 monarchs on the farm at once, almost all nectaring on the blue mistflower.”

But alas, the number of monarchs visiting Milkweed Meadows Farm is waning. Because of habitat loss, pesticides, and fluctuating weather patterns (thanks, climate change), the monarch population is plummeting — fast. According to the Center for Biological Diversity, we’ve lost 80 percent of these orange-and-black marvels in just 20 years.

BUTTERFLY BONANZA

Though other butterfly species in the eastern United States aren’t declining as dramatically, they are still at risk. And that’s a big problem for several reasons. For starters, pollinators help farmers by increasing “both the quality and quantity of fruits and vegetables harvested,” Kim said.

Butterflies are also an important link in the food chain, providing calories for all types of wildlife. Caterpillars, in particular, are a vital source of nutrition for resident and migratory birds. “After eating lots and lots of leaves, caterpillars grow to become high-calorie packages of protein and fat,” Kim explained. But it still takes a lot of these little suckers (think 6,000 to 9,000) to feed a brood of growing chickadees.

Needless to say, declining butterfly populations cause, well, a butterfly effect. “When insect populations decrease, so do populations of birds that depend on those insects to survive and reproduce,” Kim said. “If you weaken or lose a link in the chain, everything else that comes after is impacted.”

Luckily, Kim has five easy steps anyone with a yard can take to help save our Appalachian butterflies.

A MULTITUDE OF MOTHS

1. Cater Your Plantings to Both Kids and Adults.

If you want to fill butterfly bellies, you need to offer two menus: one for the kids and another for the adults. “The key,” Kim explained, “is to provide nectar-producing plants to attract adult pollinators who fly by ‘the bar’ for a quick sip.” Eastern columbine, trumpet honeysuckle, blue mistflower, cardinal flower, and turtlehead are all tantalizing treats. But you also want to grow “baby food” like milkweed, pawpaw, and sassafras to keep the youngin’s well fed.

2. Heed the 3-3-3 Rule.

When planning your garden, select native plants that bloom at different times of the year. That way, butterflies can always find something to munch — whether it’s mid-July or late October. This principle comes to life in Kim’s 3-3-3 rule. “Grow at least three plants that flower in the spring, three that flower in the summer, and three that flower in the fall.”

3. Ditch the Herbicides.

Glyphosate (aka Round Up) is one of the most harmful substances you can use in your yard. Why? Because the herbicide decimates milkweed — the primary food source for monarch caterpillars. New research also suggests that glyphosate-contaminated milkweed may affect caterpillar development. If the weeds infesting your yard really drive you up the wall, try making a natural herbicide using white vinegar and a dash of rock salt. Want something even stronger? Pick up a bottle of concentrated vinegar, spray it on unwanted plants, and watch them whither.

4. Don’t Touch That Rake.

This fall, when the leaves start to drop, be lazy. Sit on your couch for hours. Eat four bags of potato chips. Binge-watch “Stranger Things” (again). Do whatever you want — just don’t touch your rake. “Some butterfly pupae overwinter in fallen leaves,” Kim said. So, by neglecting yard work, you’re actually creating a baby butterfly habitat. It’s a win-win.

5. Remove Butterfly Bushes.

Butterfly bushes are nice-looking, sure. But that’s part of the problem. Every summer, when these shrubs unfurl their pretty purple blooms, native butterflies flock to ‘em for their enticing nector and lay eggs on the plant’s leaves. The issue? Butterfly bushes are an invasive species from China and are completely inedible. That means the butterfly babies will be left to wither in their hunger, eventually dying. To give the tots a better start, replace your butterfly bushes with native plants. The environment will thank you, said Kim. “Butterflies are an essential part of healthy ecosystems,” she added. Plus, “they are beautiful, easy to attract, and fun to watch.”

THE APPALACHIAN SOUTH'S SHOWIEST BUTTERFLIES

Markings: Deep orange wings with black veins and white spots along the edges

Host Plants: Milkweed

Where to Find Them: In meadows and grasslands across most of North America

Markings:Black with deep reddish, orange banding and white ticks

Host Plants:Plants in the nettles family

Where to Find Them:Moist areas near woods in all of North America

APPALACHIAN TIGER SWALLOW

Markings:Dusty yellow with black fringing and blue spots on rear wings

Host Plants:Since being discovered in early 2000s, research has not yet confirmed host plants

Where to Find Them:Deciduous forests at mid-to-high elevation in the Southern Appalachians.