The lodge at White Grass Ski Touring Center was built in 1959 for the Weiss Knob ski area, which closed in 1970. PHOTO BY DYLAN JONES.

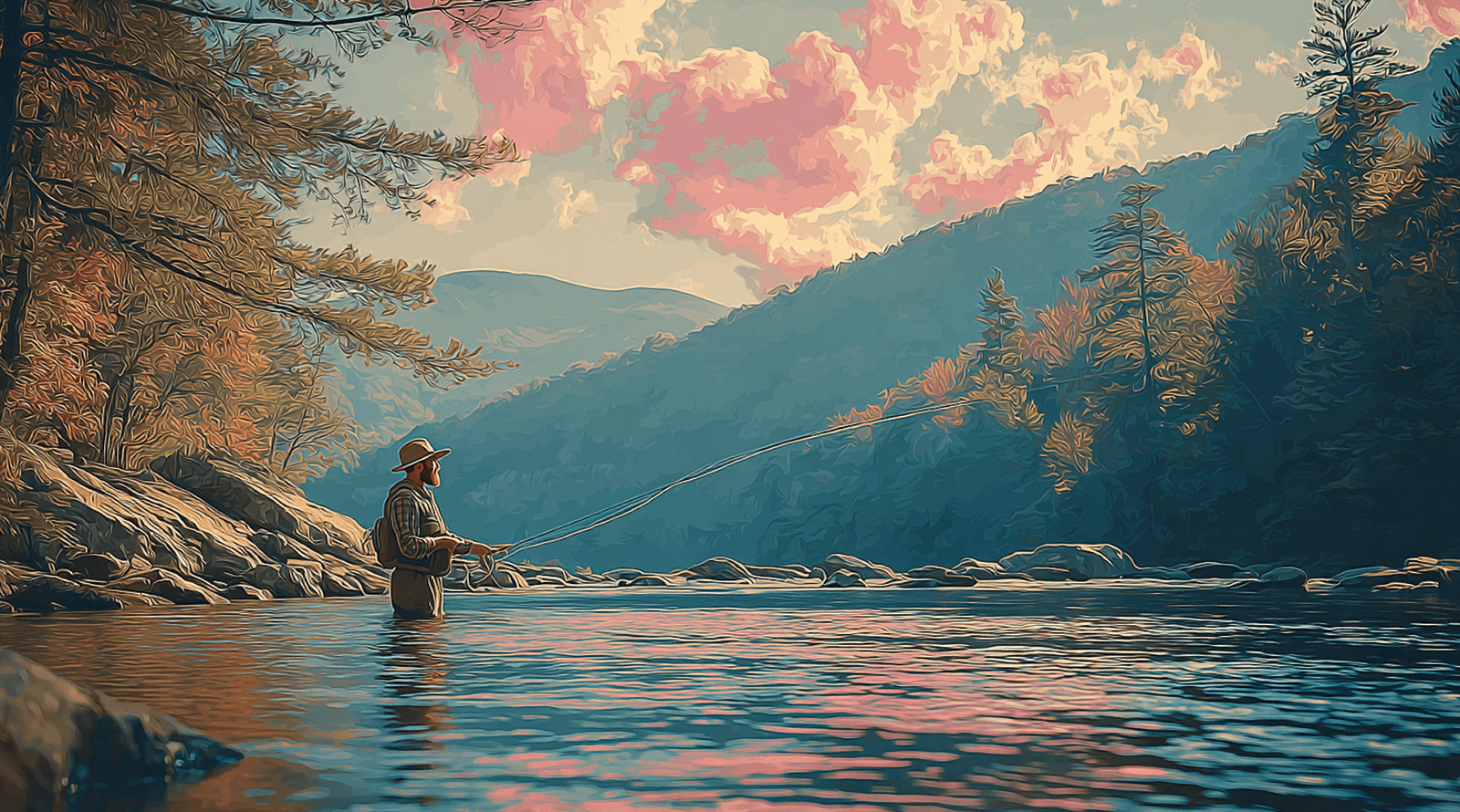

"I shuffled past evergreens laden with stunning, natural snow and hardwoods glazed in hoar frost. The trees creaked in the wind, the air smelled of purity, and my eyes jumped among the beckoning billows of untracked powder."

Chip Chase was wrong on this one.

“There’s no snow culture in West Virginia,” he told me as we chatted, masked up, in the shotgun, wooden lodge of White Grass Ski Touring Center, which Chase founded in 1981 and has run since. “I wish I could rewrite history and have a bunch of Norwegians settle here.”

Okay, so maybe the locals in this rugged, scenic pocket of Appalachia, 11 miles from the town of Davis, aren’t delivering the mail on cross-country skis. But there is in fact one heck of a snow culture there, and Chase, 67, remains at its epicenter. He’s a lithe, 5-foot-6 weather system clad in a thin ski jacket, winter pants, work boots, and a hippie-knit beanie who will riff on anything, and usually many things at once, tied together by the common theme that life, people, nature, hard work, and skiing are awesome, especially when rolled into one.

I visited White Grass during February 2021 at the tail end of a storm cycle that dropped 20 inches over four days. Two years later, during a February that’s pushed temperatures to nearly 80 degrees in some parts of Appalachia, I haven’t been able to stop thinking about that trip.

In spite of white-outs at points, or maybe because of them, people were out in force. “Best conditions!” said Dylan Jones as we methodically slid our skis up the sideline of a wide-open slope, a remnant of this area’s former life as the lift-served Weiss Knob ski area. It was 18 degrees that day, a temperature I’ve begun to wonder if we’ll ever see again, but it felt much colder thanks to a rifling northwest wind and an army of sun-blotting clouds racing overhead.

SNOW OR NOT, STAY COZY

Jones was there with his wife, Nikki Forrester, and friends for the same reason I was: to trudge merrily uphill — on skis designed for both ascending and descending — for many minutes so that we could blast back down in seconds, and repeat.

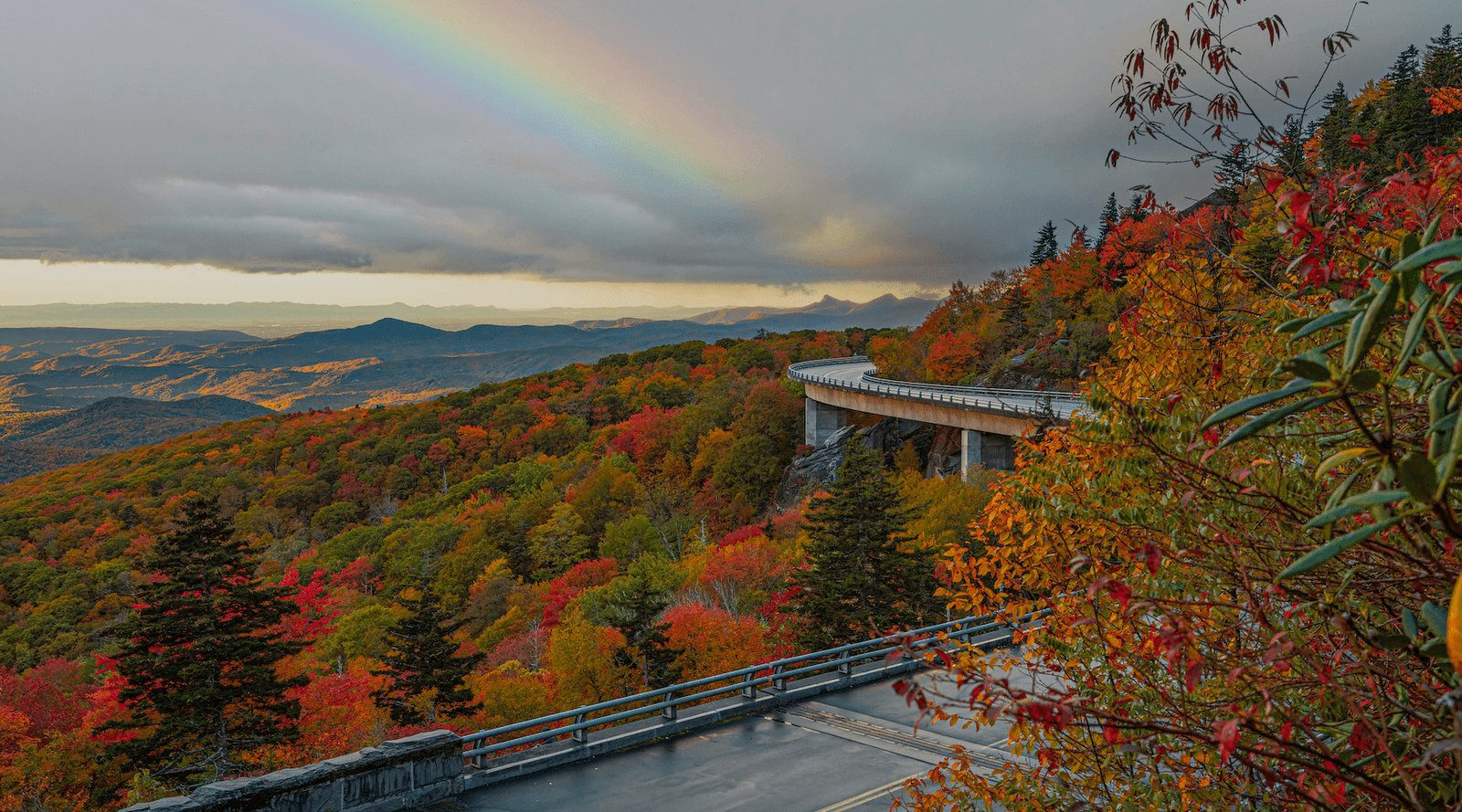

And White Grass was well suited to that ambition and still is when winter temps aren’t coaxing forsythia to bloom a month early. With 2,500 acres of terrain spanning more than 1,200 vertical feet, it includes three prominent crests — Roundtop, Bald Knob, and Weiss Knob — and more than 30 miles of marked trails, 15 of which are regularly groomed.

Then there’s the natural beauty: White Grass, sits amid tens of thousands of acres of wilderness, state park and National Wildlife Refuge, and between two lift-served ski areas, Timberline Mountain and Canaan Valley Resort.

During my visit, I split from Jones and his crew at a decaying mid-station of an old rope tow — which, legend holds, was pulled by the rear axle of a hearse that Weiss Knob founder Bob Barton had driven up there — and continued ascending along a marked trail in a forest of balsam fir, red spruce, sugar maple and birch. I shuffled past evergreens laden with stunning, natural snow and hardwoods glazed in hoar frost. The trees creaked in the wind, the air smelled of purity, and my eyes jumped among the beckoning billows of untracked powder. I can’t imagine being much happier than standing atop Roundtop, 625 vertical feet above the lodge, peeling the climbing skins off my skis, clicking back into my bindings, and taking a silken line into the glades.

Owen Mulkeen skis on the main slope above the White Grass Ski Touring Center day lodge iN February 2021. PHOTO BY JOHN BRILEY.

“White Grass is basically a backcountry ski area,” Chase told me, “founded by mountain powder skiers.” That might raise eyebrows among the legions who come to kick and glide along the undulating double-track trails or the first-timers taking lessons in front of the 1959 lodge. And in fairness, Chase embraces them all, as evidenced by the fact that many of the skiers I met — regardless of their gear — claimed to know him well. He is the hyperkinetic, beneficent godfather of freed-heel skiing the Canaan Valley. When I first arrived and asked a staff member how I’d recognize him, she replied, “He’s short. And buzzing.”

Chase went there in 1980 after trying to sustain a Nordic center through two distressingly short winters in the Shenandoah Mountains. The old Weiss Knob acreage, which in summer is a black angus cattle farm, made perfect sense for Chase’s dream: It sits on the Allegheny Plateau, beneath a ring of peaks that trap storm clouds and, though it’s hard to believe right now, it still snows a lot there, especially compared to other Mid-Atlantic ski hills. White Grass also benefits from the area’s prevailing northwest winds, which transfer oodles of snow from low ground onto the mountains. In fact, the first ski area in this valley, Driftland, opened in 1951 on a massive, recurring snowdrift, reportedly so deep that it often lingered into summer.

One reason for the New England-style winters is geography: West Virginia has the highest mean elevation — 1,500 feet — of any state east of the Mississippi River. As Barton wrote in a 1976 letter to a friend, “There is literally nothing but air between Weiss Knob and the North Pole,” a claim that actually appears to be true. That grants Arctic weather, along with gales spinning off the Great Lakes, unimpeded access to the West Virginia highlands. Barton also noted in his letter that the area, in a post-Civil War survey, was dubbed the “Canadian Valley” because of both the climate and the high concentration of far-north flora and fauna.

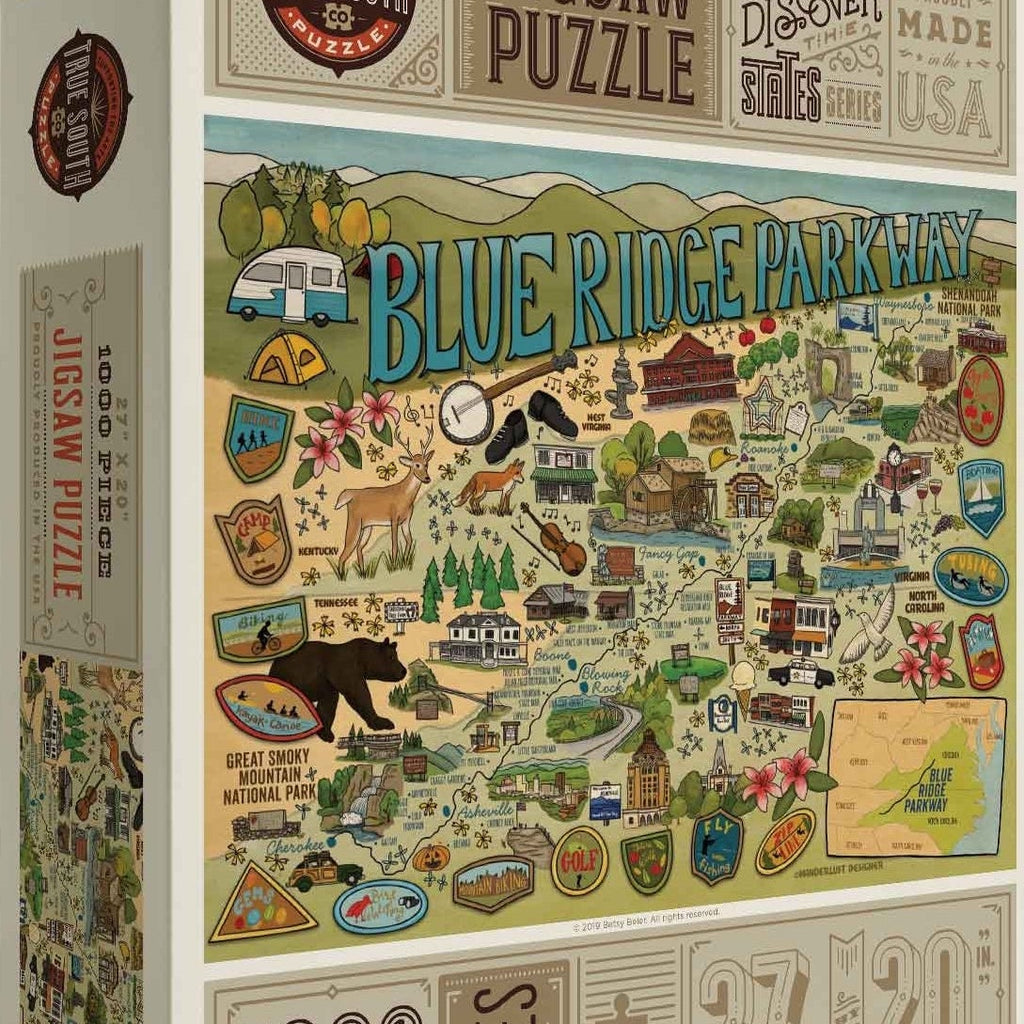

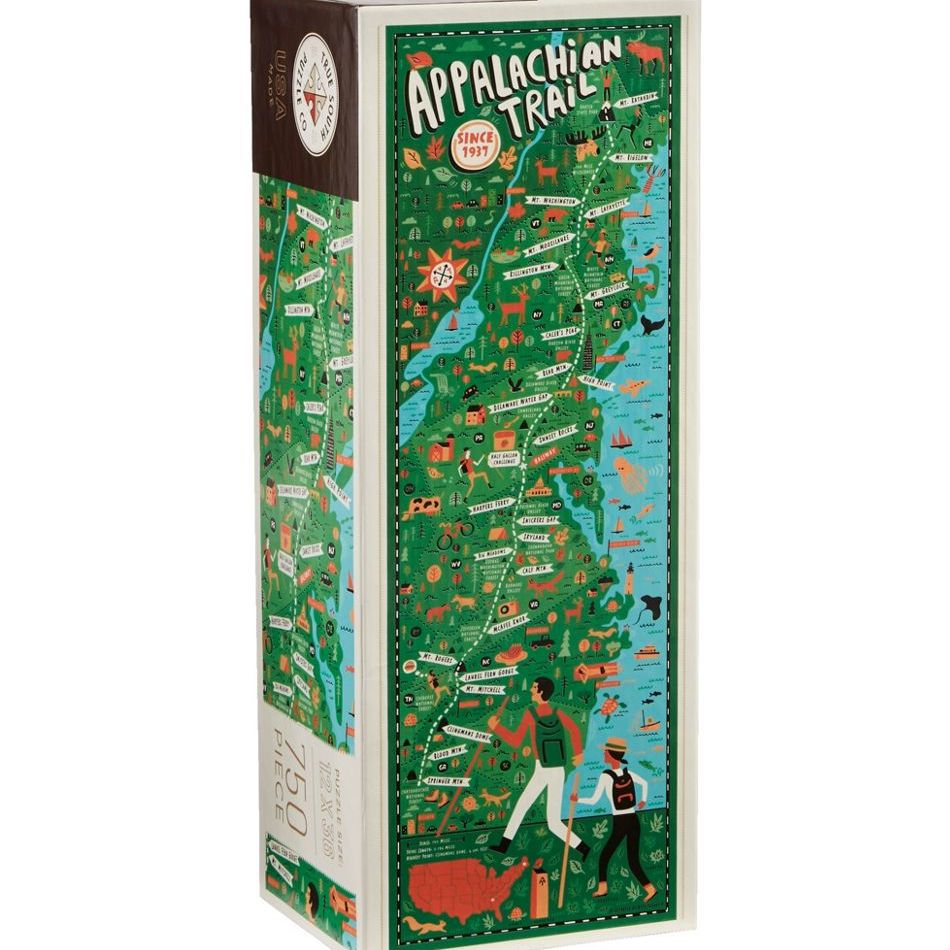

OUTDOOR FAVORITES

To be clear, the weather there is fickle, with winter rain and long droughts between snowfalls increasingly common, as illustrated by this year’s strange February. Which is why Chase is proud of his ability “to get people skiing on a one-inch base.” To maximize skiable days, he positions short plastic fences strategically to collect drifting snow, which he redistributes and grooms in a beginners’ zone called the snow farm.

On my second lap of the day up I headed for Bald Knob, 4,843 feet above sea level. I emerged from the forest into a sunny meadow of snow-topped laurels, then skated into the buffeting wind to the edge of the knob, which commands a view of the sparsely developed valley and Route 32 running like a shot arrow toward Davis. A hand-carved sign pointed me to the Bald Knob shelter, one of 10 three-walled resting spots that Chase and his crew have built across White Grass. A few have wood stoves, all have snacks (check the ammo boxes), and at least one may or may not have a stash of local moonshine tucked behind a faded tapestry (BYO cup).

At the shelter I met Mark Neubauer, a longtime grasser who went up for the day from Williamsport, Maryland. “I love this place,” he told me. “The whole peace, love and happiness vibe. I start checking their website in September to see if it’s started snowing yet.” He’s referring to the lively yet serious forecasts posted by White Grass’s dedicated meteorologist, the Fearless One — who, incidentally, was the only one among many I checked to accurately foretell the near-hurricane-strength gusts and blowing snow I drove through the prior night to get there.

I got the same vibe as Neubauer: Everyone I met, from the little kids to the gray elders of the trail, were beaming, friendly, and free with advice, as though I’d schussed onto some ascending coil to heaven.

Skiers Mark Neubauer and Ryan Fox ON Bald Knob, 4,308 feet above sea level and the second-highest peak in White Grass. PHOTO BY JOHN BRILEY.

The Friends of White Grass Ski Touring Facebook group is similarly buoyant, featuring on any given day photos of on-site fun, cross-country skiing memes, bourbon cocktail recipes, and panda videos. One post, “Had the best day at White Grass” drew the response, “It’s never a bad day at WG!”

Even now, when snow is just a memory, Chip’s website invites fans to hike, bring their dogs, and enjoy maple water and chaga tea. In a February 2023 Instagram post, Chase can be seen at a picnic table surrounded by guests with raised shot-sized glasses. In spite of a spoiled ski season, followers joke about moonshine and sunbathing in response to the pic.

Much of this speaks to the general goodness of simply being outdoors in a pretty place with a mission — to get up, down, or across whatever’s in front of you. But a lot is also no doubt because of what Chase and his community have cultivated. From midmorning to dusk people cluster around the fire pits outside the lodge, eating, drinking, and laughing.

INSTAGRAM POST FROM FEBRUARY 2023 WITH GUESTS AND WHITE GRASS FOUNDER CHIP CHASE RAISING GLASSES ON AN UNSEASONABLY WARM WINTER DAY.

“You have to treat the customer like gold, because that’s what they are,” Chase said. “There’s nothing better than helping people.” He paused, his eyes searching for his next thought. “It’s hard keeping this place going but I love seasonal work. Here today, gone tomorrow. Makes life special.”

There was 1,000 vertical feet of barely disturbed powder between the Bald Knob shelter and the lodge, but having gone so far, I was determined to press on to Weiss Knob. Thirty minutes later I reached that summit, and its vista into Canaan Valley ski resort; the adjacent Dolly Sods wilderness; and the rising shoulder of 4,770-foot Mount Porte Crayon, the fourth-highest peak in the state.

I skied two laps down an untracked cut above a buried gas line before following a telemark shredder into the trees for a final shot off Weiss Knob. En route back to the base, following a tip, I veered from the established tracks in search of powder-filled bowl. But after an hour of slogging — alone, fatigued, hungry and dehydrated — I took the first established trail I found back toward Roundtop. After one final bomb though the glades, I recovered with a sweet potato and bean burrito and an IPA from the White Grass cafe, then headed off to find Chase.

He was behind the lodge, gazing up the main slope in the dying light when a surge of joy washing over him. “Just look at those layers of skiers!” I followed his eyes from a family on the lower section to a trio of skiers by the old rope tow shack and, farther up, silhouetted high on Roundtop, two more. Chase was buzzing, with what I can only assume is renewed wonder at this nirvana he’s nurtured for 40 years. “Isn’t that awesome?”

The question was rhetorical, of course, and Chip Chase was right. Snow or not, he’s creating magical moments in the West Virginia mountains.