PHOTO PROVIDED BY THE BILTMORE COMPANY.

On the shuttle ride from Biltmore’s parking lot, I knew I should have been paying more attention. The estate’s legendary grounds, designed by the father of landscape architecture Frederick Law Olmsted, lay on either side of me, native plants looking as if they’d sprung from the earth perfectly spaced. I glanced out the window but mostly studied our driver, a retirement age woman who transfixed me the minute she said, “We’re fixin’ to drive up to the house.”

Her mountain drawl was telltale. I knew she was a North Carolina native and couldn’t help but wonder what this home meant to her. The largest in the United States, it was built by an outsider more than a hundred years ago, when George Vanderbilt II swept into the Blue Ridge, purchasing 125,000 acres and transforming it into his great estate. In doing so, he redefined this part of Appalachia, carving an economic path for the area around Asheville, one that leads directly to this shuttle bus driver’s paychecks, which she receives from George’s great grandson, the current president of The Biltmore Company.

“What’s that like?” would have been a strange question, so I simply told the driver to have a real good afternoon as I stepped from the shuttle and faced Biltmore. Some 250 rooms encased in tooled limestone, the house was too large to take in without scanning left and right. This close, it was disorienting, so I let my eyes settle on the darkened interior and inched past massive lion statues, arriving in an entry hall built to impress.

To the left, stone stairs wound around a four-story chandelier. To the right, a solarium overflowed with leaves, and beyond it, I could see a wood-paneled room with hulking pool tables.

I was traveling with my friend Neil, a North Carolinian who’d visited Biltmore before. He nudged me toward the billiard room, and I walked in silence, awe struck by marble and silk; by soaring 16th-century, Flemish tapestries; by three side by side fireplaces, each so large I could have easily stood inside.

Stopping next to a dining table designed to seat thirty-eight, I found myself wondering Who lives like this?

I’d been in mansions before, places like Marble House and Monticello, and while these estates were large and elegant too, I could picture people residing in them, working in them. It wasn’t difficult to imagine them full of life, but barely any homes exist on Biltmore’s scale. Fewer boast its grandeur. The house is at once impressive and somehow inhuman. Even when we reached its most personal quarters—his and her bedrooms on the second floor, which were once occupied by George Vanderbilt and his wife Edith—I struggled to connect the home to living, breathing people, other than us tourists who craned our necks and shuffled along the carpeted path laid to protect the floors.

And those floors do need protecting. About one million people visit Biltmore every year, spending more than $140 million locally, according to a 2012 report on the estate’s economic impact. In addition, the house employees about 2,000 people, ranging from our twangy shuttle bus driver to a rosarian—yes, that would be a rose expert—who cares for the house’s historic rose garden.

Any Appalachian area would be lucky for this infusion of capital, but I wonder if it came at a cost. Did Vanderbilt’s landgrab displace many families, and were they well compensated? How did his mansion sit with other mountaineers? We are a notably down to earth people, and this was wealth at its most flaunted. Were locals bitter about the Vanderbilt’s or just happy to see cash flowing into the region?

With docents stationed in most rooms, I had ample opportunity to ask, but, again, my questions seemed uncouth, especially in the face of such opulence. Walking through a Louis XV inspired bedroom, complete with silk velvet wallcoverings imported from France, I imagined myself alive when the house was built. The person I am today would have enjoyed knowing Biltmore was my neighbor even if I was never invited to visit, but how would I have felt as a 19th-century mountaineer, the kind who fell trees himself to build a one or two room home?

Indoor plumbing and electricity would have been exotic to me, so this house, with 43 bathrooms and electric buttons to summons help, would have seemed like a fairy tale, as mythical as Camelot, simply unbelievable.

***

Were it not for Neil, I would have missed the house’s best part. As we returned to the lobby, he said, “This way,” pointing to a discreet doorway, and within inches, everything took a turn. Downward stairs were lit with simple sconces, a kind I’d seen in many older homes. The walls were unadorned, and where the stairway ended, a brick-lined tunnel began. It led to an unassuming cellar, a large room with bare concrete floors that would have been unremarkable were it not for an amateur mural, painted in grotesque yellows and greens, that encompassed all four walls.

Neil pointed to our brochure: “In April 1924, Cornelia Vanderbilt [George and Edith’s sole child] married the Honorable John Francis Amherst Cecil, a British diplomat. In 1925, the young couple, joined by family and friends, spent several weeks painting these unusual wall scenes for a New Year’s Eve party.”

Unusual was an understatement, more like menacing. A creepy village filled with cats climbing on rooftops and bizarre flowers towering over the houses—this was the kind of graffiti I’d expect from teenage stoners but not American royalty. It was so unlike any of the art upstairs—John Singer Sargent’s formal portraits and Anders Zoran’s depiction of a Victorian ball—beautiful but staid paintings, art built to impress. This messy mural was something else. It showed whimsy and a dark humor. Instead of obfuscating personality, it revealed it, leaving me gawking, entranced. For the first time I could picture people living in Biltmore.

I saw the young couple dabbing at the walls with friends, all in paint splotched clothes. I imagined cooks and laundry boys cutting through the room, laughing at this messy scene. Even their long ago New Year’s party seemed possible. It was surely an elegant affair. These were Vanderbilts after all. It must have extended beyond this humble room to the entire mansion with guests dressed to the nines, yet I could envision their hugs and toasts and kisses, their flirtations and loud children. I could see an older couple retiring early and a sullen loner studying his champagne in the corner. This silly mural transported me to the jazz age, a time of frivolity, of great change, when Victorian pretense began to give way to modern pragmatism, a time when even the extremely rich began to act more human.

***

Wind gusted too hard to tour the grounds, so Neil and I bought hot cider in the stables-turned-shops and took shelter behind a stone wall to watch for the shuttle bus. If we had the same driver, I told myself, I’d sit right behind her and find a way to ask about her Biltmore experience. We shivered and sipped as dusk faded to pure darkness, until the shuttle arrived. Other tourists poured out of porticos and doorways, having taken shelter just like us, and many reached the vehicle first. Interior lights revealed their huddled but orderly silhouettes, filling seats near the front, and a new driver, this time a man. I greeted him, hoping to hear some twang in his response, but he replied, “Hello,” with an accent as plain as a newscaster’s.

Neil and I took the only seats, near the back. With bus-mates chattering about the tour and the cold around us, my disappointment over the driver faded and was replaced with a question: if Anderson Cooper ever visited, would he arrive and leave like this?

He is a Vanderbilt after all. Since his family still owns the estate, maybe he’s allowed to drive right up to the door. Maybe he can even tour the house during off hours.

Small luxuries, I thought, knowing that none of the Vanderbilts could afford to live in Biltmore now. Their name does not even appear in Forbes’ annual review of America’s Richest Families. That list is now topped by, the Waltons, who’s retail empire is based in the Ozarks, making them well-healed hillbillies.

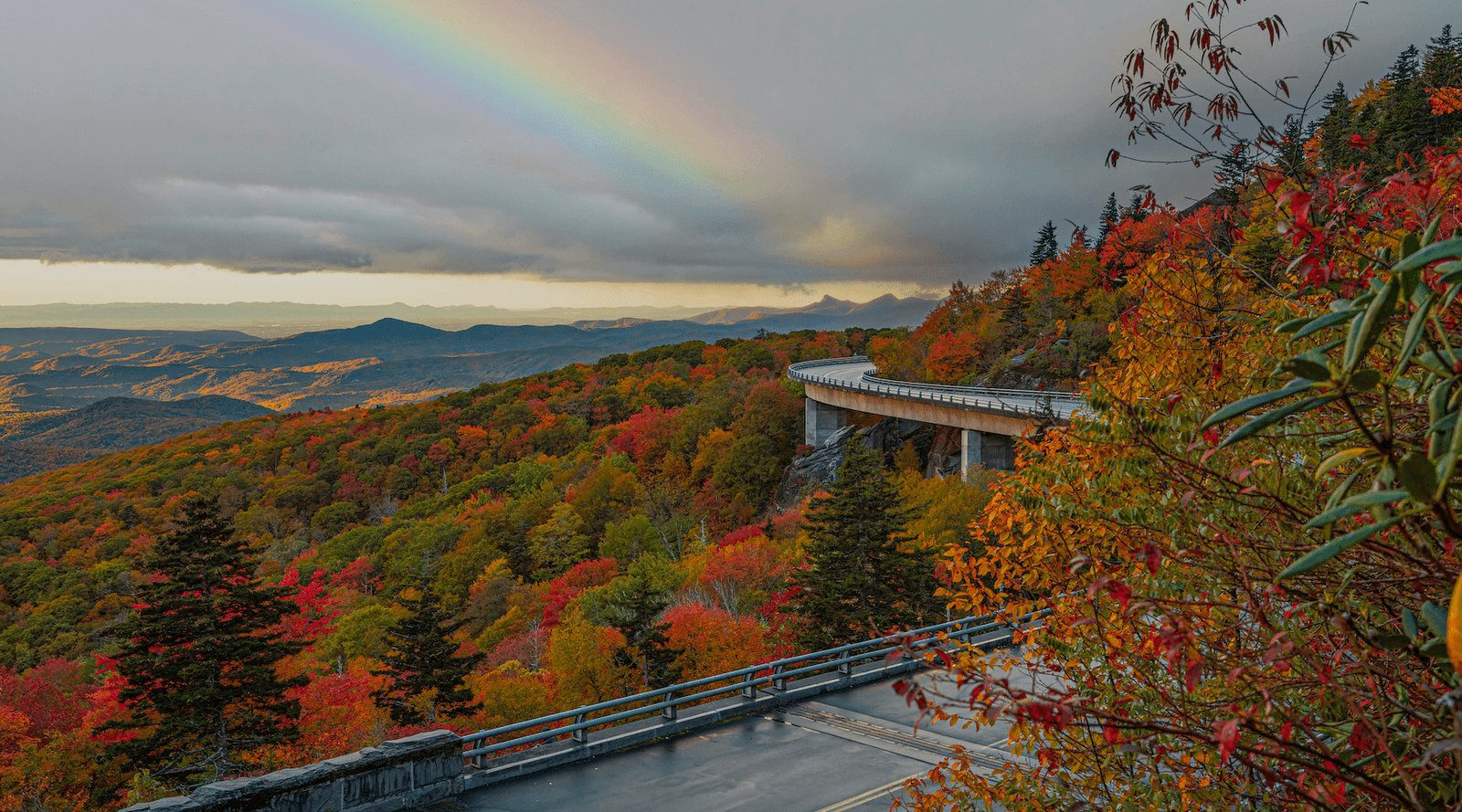

Time has a way of leveling things, I figured, like the navy blue peaks I saw in the distance, rounded over millennia, or the quality of life for mountain people, who have enjoyed plumbing and electricity for decades now.

When you mention Biltmore around them today, most locals get excited and ask if you’ve been. Whatever discord their ancestors felt is long gone, leaving only enthusiasm for this great estate, for the mansion that must have been a mile away when I stepped onto asphalt in Parking Lot C. Just as the shuttle began to roll again, snowflakes landed on my nose, a complete surprise, and I wanted to run, to catch the bus and go back to the house because, like anyone, I knew Biltmore would be breathtaking in the snow.

*Acknowledgements to Humans of New York, a column in The New York Times with a title that begs for imitation.