I figured that Ed George was a spitfire the second time we spoke. I was tearing around my kitchen gathering Thanksgiving essentials. I'd already packed three bags of groceries and was hoping to avoid a fourth. I called his number and left a voicemail. "Hi Ed. This is Mark Lynn. We're headed up today. I wanted to see if the place had a few things. Please call me back."

We'd talked once before. When I made the reservation for his rental cabin, The Homestead. I noticed then that his voice was older and spry, usually a fun combination, but the call was brief. I couldn't glean much.

Ed called back while I was packing spices. When I answered, he announced himself like a celebrity DJ ready to put me on air. "Mark," he said with resonance and a pause, "This is Ed George."

"Ed! Thank you for calling me back." I launched right into my list—hand mixer, coffee maker, rolling pin, mixing bowls, measuring cup and spoons.

He politely confirmed each and began to chuckle toward the end, assuring me that the place was well stocked. I thanked him, thinking we were about to hang up, but before I said goodbye, he guffawed unexpectedly. With a little snort, he said, "I am glad I’m not the one driving from DC!"

Normally when you hear this kind of thing, it suggests pity for you, the weary holiday traveler, having to risk fender-benders, fast food indigestion, and roadside bandits just to reach your destination.

Coming from Ed George, though, the statement sounded literal. He seemed truly relieved to be in Berkeley Springs, knowing that his holiday destination was no further away than his dining table. If there was any undertone, it was a self-affirmation that said, “Man, have I got good sense living in West Virginia or what?”

I hung up laughing and excited to meet Ed.

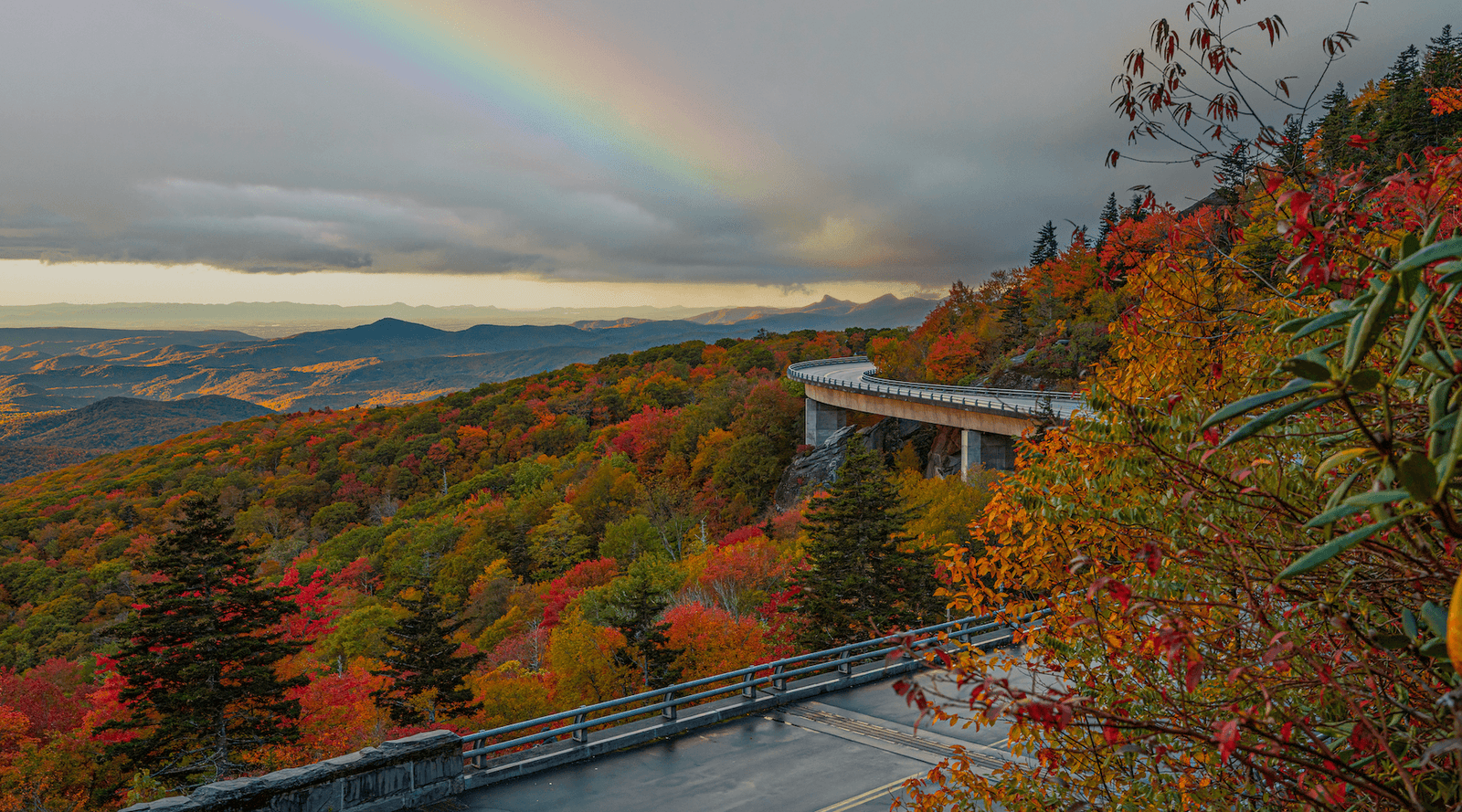

Per his prediction, our ride to Berkeley Springs was horrendous—bumper-to-bumper traffic until the West Virginia border. By then, it was dark. We navigated back country roads until we found the unpaved one that led to the house. It was marked with an aging little sign that read “H MES AD.”

Gravel crunched under our tires for a mile or two. The road gave way to a field right in front of the cabin, which was lit up like Christmas. Porch lights and lamps glowed, warming the frosty night.

We grabbed our dog and bags, and hustled inside. The heat was already on, and the wood box was filled. Towels were out, and the beds were made. Someone—maybe Ed—had prepped the house. It was instantly cozy.

Exposed beams helped. Thick as my thighs, they supported creaky floorboards over head. They were low, raw, and at least a hundred years old.

At the back, the ceiling vaulted higher. This was over the dining room and kitchen, which was one big room. It was a traditional space with homemade cabinets, bench seating at an antique table and a six-foot long butcher-block counter, the surface of which had deep divots. It had aged to a beautiful muddled brown.

At the back, the ceiling vaulted higher. This was over the dining room and kitchen, which was one big room. It was a traditional space with homemade cabinets, bench seating at an antique table and a six-foot long butcher-block counter, the surface of which had deep divots. It had aged to a beautiful muddled brown.I thought, “This is the perfect place to pour a bourbon,” and made two drinks.

We sipped them by the fire, petting the dog and pointing out charming quirks --stained glass blocks embedded in the wall, a Porgy and Bess album on the shelf, Tibetan prayer flags hanging over the stairs. When our glasses were empty, we called it a night.

On Thanksgiving morning, the wind blew like it had a grudge. It bent trees half over and forced the smattering of snowflakes into sideways streaks. When it whipped around the house, it whistled, but the hand-hewn logs and chinking held. I didn’t feel a draft.

Nora and Jess, pals from DC, arrived around noon. Between roasting the turkey and rolling pie crust, we nosed around the place. I took photos of oddly angled walls and unexpected spots in need of replacement windows. My partner Ryan noticed a note explaining that the cabin had spent most of it’s life in Virginia. It was relocated in 1980.

That made sense. The windows and heating units were newer, and upstairs, under glass on an antique desk, I’d found pictures of a couple. They looked like young retirees. With long haired friends, they were placing logs and finishing floors. The man must have been Ed, then a fit 50-something with big eyes and a bigger smile. The woman was stylish even when she was doing manual labor; I assumed she was his wife. They clearly didn’t hire contractors to disassemble the cabin and move it. In what looked like a labor of love, they did it log-by-log.

All day I wondered if we’d hear from him. I knew from the online map that he lived nearby, but the Thanksgiving meal came and went—turkey stuffed with sausage dressing, baked sweet potatoes, green bean casserole, homemade bread, cranberry sauce, an apple crisp and pies. It was an obscene amount of food for four people. We lingered, laughing and talking. No guests came calling. Eventually we retired to the living room, where Nora thumbed through a binder by the fire.

There were poems inside—silly ones, written by Ed. (I wish I had thought to copy one.) There were postcards from prior renters and brochures for nearby attractions—the famous hot baths, a downtown antique mall, the arts center, a nudist resort. We lingered on the last one, laughing like preteens. Then Nora flipped on through the plastic sleeves.

She stopped again when she reached an essay. Ed had served in World War II. He explained that he had been trained as an airman, and one of the great regrets in his life was that he hadn’t deployed.

She stopped again when she reached an essay. Ed had served in World War II. He explained that he had been trained as an airman, and one of the great regrets in his life was that he hadn’t deployed.He recalled a night of drinking with an older soldier; the man was bombastic, telling bigger than life stories about adventure in the trenches, bawdy memories, funny tales. He glorified the battle, and Ed told him, laughing with the others, “ I wish I’d been there.”

Suddenly, the man turned serious. He looked Ed in the eye, stone sober, and slowly said, “You didn’t miss a damned thing.”

Still, Ed spent decades with survivor’s guilt echoing around inside him. He wondered, “Why me,” and in what I consider an act of unusual bravery, he wrote his worries down for his guests to see.

The next day, Ed arrived. We were in the living room. Everyone was reading except for me. I stared out the plate glass window at the Sleepy Creek Mountains. Beyond the field and perhaps three miles of bare trees, a low ridge stretched at an angle to the house. My hands rested on my open laptop. In the blessed silence, I ignored the story I’d been writing and watched birds circle near the mountaintop.

“Hawks,” I thought.

Thud. Thud. Thud. Everyone jumped when we heard a hearty banging on the side door. The dog went wild, barking. Ryan grabbed him. I shoved my computer aside and lunged for the knob. Outside, three faces stared at me—a smiling old man and two notably younger women.

I immediately remembered the nudist resort and the lively glint I’d heard in Ed’s voice. “My Lord,” I thought, staring blankly at the ladies flanking this octogenarian, “They must be progressive around here.”

Then another man stepped up. I came to my senses and waved them all inside. In a sudden flurry of conversation, introductions began.

“Ed, Ryan, Nora, Jess. And I’m Mark. We talked on the phone.”

“Yeeeees,” Ed said, throaty and loud. He grabbed my hand to the wrist and shook with the grip of a dock worker. Then he waved his arms around, introducing his people—his son, his daughter-in-law and a guest from Colorado.

For a flash, I felt bad about my off-color assumption, but I couldn’t worry for long. Ed launched into a story about community theater. He’d performed a number of roles, he explained, acting out each—the grumpy old man, the funny old man, the lonely old man. His face morphed between the emotions, and when he referenced one character who died, he laid his head upon on hands as if sleeping. This gave way to a little bow.

“I’m afraid that I’ve been typecast,” he said, laughing, and he guided his people on through the house like an energetic docent.

Their tour was fast—a breeze through the downstairs, a peak around the patio and then they were headed back to the sleeping porch, the way that they had come in. Steps from the door, Ed said he hoped we’re having a wonderful stay and handed me a scrap of paper. It was a handwritten bill for the rent.

Looking me straight in the eye, he instructed, “Relax, have fun, enjoy the fire.”

I wanted to stop him there, put my hand on his shoulder and ask if he knew what he’d made. This cabin was more than a weekend rental. It chronicled his bright life. The unexpected rush of color through stained glass; the crooked but rock-solid timbers; a bed on the screened porch, turning a typical outdoor space into a novelty--he had embedded his vibrancy in the walls and floors and furnishings. I wanted to tell him that it was a joy to stay somewhere with such heart, but I wasn't as bold as Ed. I couldn't bring myself to say that to a stranger.

“Thanks. Yeah,” I mumbled instead, “We’re having a great time.” Staring dumbly at the bill in my hand, I added, “I’ll leave the check on the, uhm, table?”

He stopped under the split log doorway and leaned toward me. With a dramatic pause, Ed smirked, and said, “You better.”

He shut the door and through it, I heard him laughing at himself.