Child labor was among the abuses in Pa. mines. shot in 1911 in South Pittston by Lewis Wickes Hine, this photo was provided by Library of Congress.

“Despite providing energy that largely ran the entire country, many of Appalachia’s

hardest working people were treated like industrial serfs.”

Imagine working 11 or more hours a day in the dark, deep underground, only to go back to the surface at the end of your shift to find that there’s little light in your life up there too. That was reality for countless Appalachian miners for about half a century.

Many were paid in “scrip” instead of cash — currency that could be used in stores owned by mining companies and nowhere else. Coalminers were sometimes provided with small houses (some basically shacks) by mine owners, but those came at a high price. When miners pushed too hard for better working conditions or attempted to unionize, they and their families could be forced out of their homes and left to live in whatever was available, including chicken coops and tents.

Despite providing energy that largely ran the entire country, many of Appalachia’s hardest working people were treated like industrial serfs. But instead of leaving them defeated, this mistreatment made them angry and ready to fight for their rights.

Mining and labor historians often focus on southern parts of Appalachia, like West Virginia and eastern Kentucky, but life was just as hard in other mining communities, including those in Pennsylvania’s mountains. Miners there helped pioneer the burgeoning organized labor movement. In fact, central Pennsylvania miners were among the first to unionize in what was a forerunner to the United Mine Workers of America (UMW). More than 46,000 Pennsylvania miners joined this union and were willing to strike — losing their incomes and often their homes — for better working conditions.

MADE IN PENNSYLVANIA

Every purchase helps keep our Appalachian magazine alive, thriving, and free to readers like you.

Between 1915 and 1922, miners went on strike more than 1,000 times in Appalachian Pennsylvania. During that period, post WW1 inflation also led to a massive nationwide UMW strike in 1919. Fear about coal shortages alarmed the government and big business, but instead of working with the miners, these powerful institutions declared war.

After a federal judge deemed the nationwide strike illegal, the Department of Justice sent investigators into coal towns to target union leaders. They tapped the phones of leaders in Pennsylvania and elsewhere, and encouraged the immigration and nationalization authorities to threaten Appalachia’s many immigrant workers with deportation. Troops were sent into coal towns to keep order, and courts made it illegal to demonstrate or to hold public meetings. Miners could be arrested for just carrying the U.S. flag.

Violence, including lynchings, rapes and beatings, became common as mine owners, backed by federal and state governments, fought for control. The Ku Klux Klan, which was becoming a major social movement in the 1920s, helped to reinforce the companies’ power through intimidation and violence. More than 125,000 western Pennsylvanians joined the Klan, including many mine officials. In Cambria County, Klansmen marched through the town of Lilly, fighting with union members and leaving two workers dead.

Even owners who had agreed to union terms found ways to crush mine workers. Many outright closed their union mines, putting up to 2,000 men out of work at a time, and later reopened them, often under “new” ownership and nonunion labor.

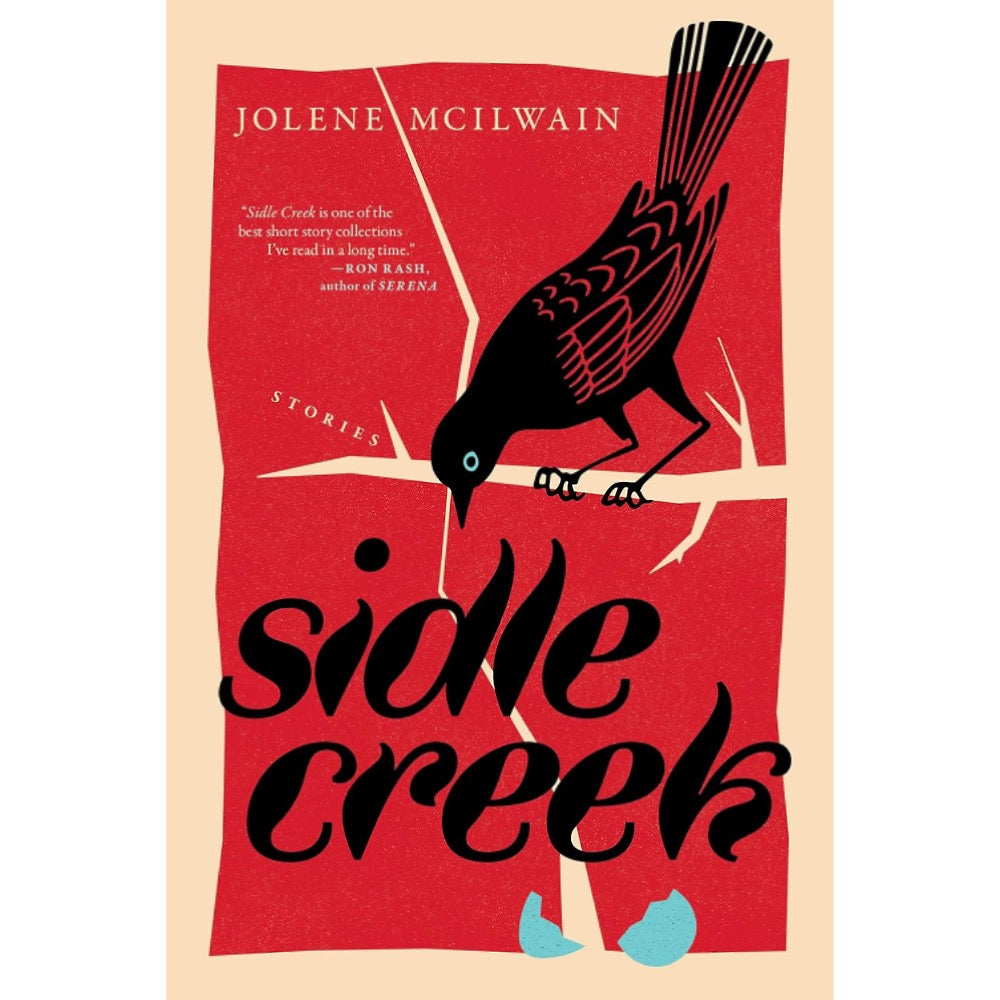

Taut prose and gorgeous imagery won this Appalachian Pa. book praise as an NPR and Library Journal Best Book of the Year. Shelf Awareness called it “a rare gem, a compelling blend of nature and humanity perfect for fans of Barbara Kingsolver..."

(Every purchase helps keep our Appalachian magazine alive and thriving.)

By 1927, almost all central Pennsylvania mine operators had broken their agreements with the union, including the Clearfield Bituminous Coal Corporation (CBC) in Rossiter. When the company decided to shut down the mine and later reopen it with nonunion workers, the local sheriff quelled unrest by declaring martial law—creating mandatory curfews and threatening anyone who broke his rules with three to seven years of imprisonment. Soon, almost every central Pennsylvania county had made similar proclamations.

These brutal tactics worked. By 1929, the United Mine Workers of America only had 100,000 members, down from 400,000 in 1919. But the battle wasn’t over and neither was unionization, thanks to the heroic efforts and extreme sacrifices of central Pennsylvania coalminers, union members, and their families.

The 1930s saw the passing of The Wagner Act (also known as the National Labor Relations Act), which established the first national labor policy of protecting the workers' right to organize and conduct collective bargaining. It also saw the formation of the Committee for Industrial Organization (CIO) in Pittsburgh to foster industrial unionism.

Learn more about this harsh period in Appalachian Pennsylvania with this documentary about the period. “What you see in the documentary was never taught in schools,” said Dr. James “Jim” Doughtery, who produced the piece. “And the more I investigated, the angrier I got.”

Dougherty’s historic research later inspired him to found the Northern Appalachian Folk Festival and the Jim Rogers & Ken Holliday Folk School on the Arts and Humanities, which helps preserve Appalachian Pennsylvania’s rich history and traditions.