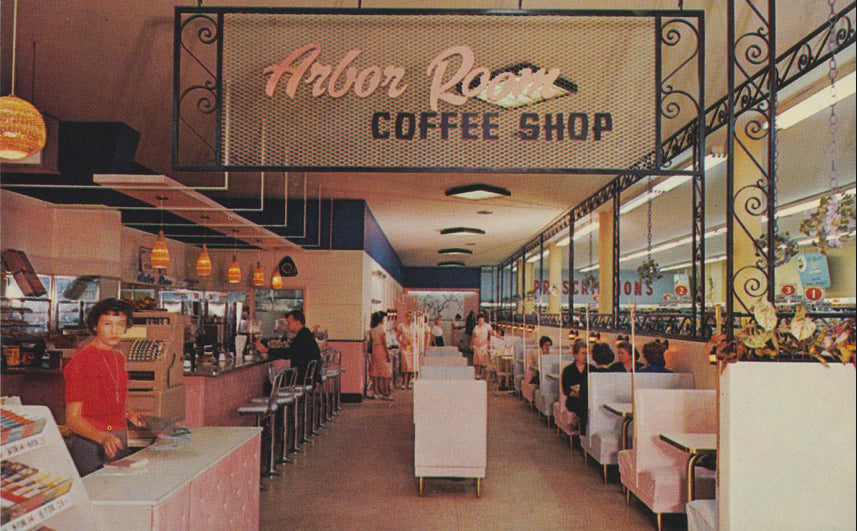

When Roanoke's Crossroads Mall opened in 1961, it was like Christmas and Fourth of July combined. This was the first enclosed, suburban shopping center in all of Virginia. It drew customers and curiosity seekers from miles around. According to Steven Swain, a blogger who traced the mall's history, "Developer T.D. Steele and his designers created a unique and popular shopping experience for an eager public. Throngs of shoppers left the long-dominant downtown to stroll through a grand two-story interior shopping hall."

By 1962, two more suburban malls had opened in Roanoke, and around the same time, they popped up in cities and towns throughout the Appalachian South. Crossroads ushered in a new way of living, one that prioritized convenience and comfort. Shoppers no longer had to worry about weather, wind, or mud puddles. Their world was being primped and paved, and it was built to a new scale--one that fit the automobile. Errands were measured in miles not blocks, and walking would soon become outmoded.

Decades later, there is a lot of buzz about what was lost when we suburbanized the nation, but fifty years ago, Crossroads was groundbreaking. It helped mark the dawn of an era.

To commemerate this anniversary, The Roanoke Timesasked readers to share their memories about the mall. Surprisingly, only two have been posted. The first commenter, a fellow named Greg, glows over Crossroads:

"Crossroads was where we always went to see Santa and I remember him arriving by helicopter near the J C Penney’s warehouse which is now Gold’s Gym. There were so many cool things at the mall. The water fountain outside Penney’s, TIMEOUT arcade, Orange Julius, Michaels Bakery, etc. etc."

The second post (which is currently pending review) is mine, and it takes a different tone. I remember most of the stores that Greg names but in a less cheery light. I grew up about a mile from Crossroads Mall. We moved to the area when my parents divorced. My mother left her three bedroom house, the first and only property she ever owned, for a third-floor apartment near a rough and tumble drag called Williamson Road. This was the early 1980s. By this point, both the mall and the neighborhood had passed their prime, and some days, it seemed like my family had too. The Roanoke Times probably wasn't expecting memories like mine, but for me, Crossroads wasn't filled with wonders. It was a reminder of all that we'd lost.

***

I grew up one walking mile from Crossroads Mall. I say "walking" because that's how my family got there. We had no car, so on the day that food stamps arrived we hoofed up Roanoke's backstreets; across Hershberger Road's buzzing six lanes; and over forty yards of parking lot, which sizzled during the summer and swept wind like the plains all winter.

Most any time of year, we rushed for Kroger's automatic doors. Inside, we'd acclimate, wiping our foreheads or stripping off winter gear. We always had a carton of empty Dr. Pepper bottles, and I'd beg to slide them into the tall, metal deposit rack. It enthralled me, because from my height, it looked dangerous, like some mammoth glass-filled cage. When we had the change from our deposited bottles in hand, we'd begin to shop. Cost Cutter frozen broccoli. No-name butter cookies. Bagged breakfast cereal with poorly drawn mascots that no one recognized. Nearly expired meat. My brother and I would beg for names we knew from television--Snap, Crackle, and Pop; Pop Tarts; Pepperidge Farm--but Mother would tell, "This tastes just the same."

Our generic boxes and cut-rate finds would fill one, sometimes two, grocery carts. Mother wasn't eager to come back and do this again, so by the time we headed for a checkout lane, we'd have enough food to last all month.

Most cashiers smiled as we approached, overlooking our heap of discount groceries and the brightly colored, pretend money that paid for it. Occassionally, though, one would raise her brow or roll her eyes. That's when Mother turned fierce. After hauling two kids and clanking soda bottles for a suburban mile, she wasn't going to be judged. She'd jut her neck out, cock her head, and stare the woman down. I don't recall a cross word ever being uttered, but you could cut diamonds with her glare.

God love her; Mother gave surprisingly little thought to how we'd get all of that food home. Usually, we carried it in our hands--her hauling as many as eight bags, my younger brother with two, and me dragging three or four, whining about the taunt plastic that dug into my palms. Some days, Mother couldn't endure my complaining, so we took the bus. It reduced our walk to just a few blocks, which was better, but nothing compared to the few, glorious occasions when she threw her hands up, headed for a pay phone, and said, "Cost be damned. We're taking a cab."

With tip, I remember it ran about ten dollars. That was enough to force Mother, days later, to haggle with the electric company because our payment came up short, but it seemed well worth it at the time. After she called the cab company, we would stand at the curb outside Kroger, eyeing the long lane that extended clear to Kmart. We'd scan back and forth like any other family. To passersby, I figured it looked like we were waiting on some father-figure to pull the mini-van around. I could even convince myself of that. I'd block out the long walk there, the food stamps, and the coming cab. For those few minutes, I'd pretend that we were as normal and nuclear as anyone.

Then the yellow Mercury Grand Marquis would show. As soon as I spotted its unmistakable checkerboard pattern, my fantasy would shift. Where we were all-Americans a moment before, seamlessly blending at the mall, the cab gave us a mysterious edge. I imagined that we were set apart, that we were sophisticates who were always being driven around. The cab's trunk would spring open, and a friendly stranger would load our groceries. All we had to do was sit down. I took my time, now hoping to catch shoppers' eyes. I'd hold the door for my mother and brother, lingering outside the cab until one of them said, "Mark, git' in!"

I would ease onto the cushioned seat, and leave the door ajar, inviting shoppers to peek inside. They did so every time. Cabs picked people up in New York, in London, in Paris but not in Roanoke. It was a novelty. For all they knew, we were visiting from one of the world's great cities, shopping for provisions to take back to our downtown hotel where, later, we would dawn formal wear and wave for another cab. We'd be off to dinner with the mayor, local gallery owners, and perhaps a TV news anchor. We were guests. We might even be stars.

Our dinner companions would coo whenever mother slipped me sips of champagne. They'd give use private tours of their galleries at midnight. One would offer us his French countryside home for the summer, saying, "We just don't make it out there enough. Go. Go," and then he'd lean down to my height and wink at me. Whispering so that only I could hear him, he'd add, "Don't worry. I'll have the house staff fill the kitchen with all of your favorite brands."