If trains ran deep in my subconscious, it was because they criss-crossed my waking world. We couldn't drive two miles in Roanoke without going under a trestle or seeing a railroad crossing arm. Whenever we stopped for a passing train, I counted the coal cars and bounced in place, excited about the big finale—that jolly, red caboose at the end.

I didn't know it then, but my town was the exception. By the 1970s and 80s, when I grew up, highways had stolen nearly all passenger and freight traffic, and trains were growing rare in much of the country. As home to Norfolk & Western Railway (N&W), Roanoke provided a throwback experience, a window into rail's golden age.

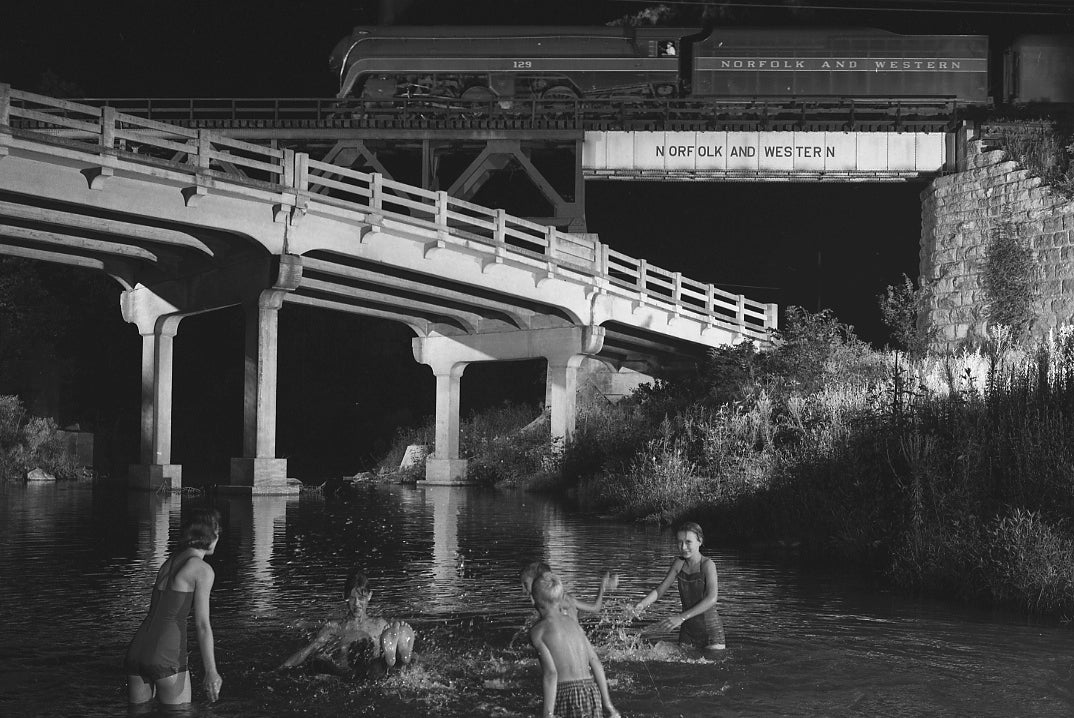

[caption id="attachment_9636" align="alignright" width="294"]

"Waving to No. 2" by O. Winston Link.[/caption]

"Waving to No. 2" by O. Winston Link.[/caption]Luckily, it still does. If you love trains, you can visit my hometown and see a functioning rail yard, complete with a factory—the East End Shops—where locomotives were once built from scratch and where, today, expert mechanics restore these machines, some as much as 25-years-old, into like-new models.

You can tour the Virginia Museum of Transportation, and board the world's most powerful steam locomotives—a massive Class A 1218, known as the Mercedes of Steam, and the sleek Class J 611. They are the last of their kind, reminders of an age when steam engine's revolutionized travel.

You can also visit the O. Winston Link Museum, and relive the final days of that age, the late 1950s, when diesel replaced steam and those locomotives were retired. Link, the museum's namesake, was a commercial photographer. Based in New York City, he took pictures of fashion models and body lotion for a living. While he was a fan of trains, he never imaged that he would take some of the most enduring rail images in history or that his career would reach new heights in Appalachia.

In 1955, Link visited Staunton, Virginia to photograph air conditioners at a Westinghouse plant. While there, he heard that a steam engine would be passing through Waynesboro. By that time, just one U.S. railroad still ran these old trains—N&W—so Link knew he could get some unique shots. What he didn't expect was the local rail depot. He said that when he walked through the door, it was like stepping onto a classic movie set—a bare bulb overhead, a telegraph machine, a clerk's eyeshade hanging just so. He realized that communities had developed alongside these tracks, special places that might not be around much longer. Link committed himself to capturing them on film while he still could.

What resulted were some of the period's finest photos—portraits on a grand scale, steam trains and children swimming, steam trains and teens at a drive-in, steam trains as seen through a living room window and from a gas station. The shots were as much about the people who lived around the trains as the trains themselves.

Mike McNeil, Director of the O. Winston Link Museum, says that he and his staff strive to reflect this vision. "We try and tie everything back to the effect that steam locomotives had on the local communities," he says, "We really explore what everybody's daily life was and how interaction with N&W affected communities throughout Appalachia."

Many of Link's intricate compositions were shot at night. He once said, "I can't move the sun — and it's always in the wrong place — and I can't even move the tracks, so I had to create my own environment through lighting." With help from assistants, he would craft complex arrays of mercury flash bulbs, stringing as many as eighty of them together with a trigger that went off just as the train passed.

[caption id="attachment_9640" align="alignleft" width="295"]

"Waiting for the Creeper" by O. Winston Link. Shot at the Vesuvius General Store.[/caption]

"Waiting for the Creeper" by O. Winston Link. Shot at the Vesuvius General Store.[/caption]At the museum, you can experiment with lighting too. "We have interactive exhibits, including sculpting with light," says McNeil, "which explores the effect that different flashes have on images."

You'll also find a reconstructed general store, one that Link shot in the town of Vesuvius, Virginia. The store's countertops, cash register, butcher paper dispenser, and scale are the very same ones seen in Link's photo.

The museum's building itself is even a treat. A former train station that was originally built in the Queen Anne style, it was dramatically remodeled by the renowned industrial designer Raymond Loewy. When construction was completed in 1949, the new N&W passenger station was a sleek modern building, complete with vast glass walls and Roanoke's first escalator. Today, it serves a fitting new use—displaying Link's fine photos, artifacts from the era, and also the sounds of steam locomotives. A man of many interests, Link dabbled in audio. While on shoots, he would record the same trains he photographed.

Below is an image and a clip that he captured in Rural Retreat, Virginia. It was Christmas Eve, 1957, and Link arranged for a local organist to play church chimes just before Train 42, The Pelican, arrived. The steam engine you hear, a Class J Number 603, was making one of its final runs from New Orleans to Washington, D.C. Seven nights later, the last steam engine in the U.S. would be retired.

Listening to it, what do you hear? What do you picture? What do you think life was like in this small Virginia town on Christmas Eve nearly sixty years ago? What would have been lost were it not for this one photographer's ingenuity?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fbzAJoW34DM