AUTHOR SILAS HOUSE. PHOTO BY C. WILLIAMS.

“I started this book because I lost my aunt, who I just adored. She was like a third parent to me, and I was frozen after she died. For the first time since I was a teenager, I couldn't write. And so, I thought, ‘I'll just write about what I'm going through.’”

I first met Silas House while pursuing my MFA in writing at Spalding University, where he is on faculty. His dedication, good humor, and fluency with the craft wowed me from the start.

In late 2022, Silas released “Lark Ascending,” a book that landed in my hands at the perfect time. Without detailing difficulties, suffice it to say that 2023 has been a year of deep grief for me, and I needed this poignant story in this moment. While I never expected to find solace in a post-apocalyptic novel, Silas showed how true humanity can be our saving grace against the backdrop of a catastrophic, man-made disaster.

As a born Mainer and longtime resident of a one-store-and-a-post-office town in West Virginia, place matters to me. I was also pleased to see Silas treat the places in his novel lovingly, particularly the overlooked parts of Appalachia.

I’m not surprised that “Lark Ascending” has been recognized by publications ranging from the Los Angeles Times to Garden & Gun and is a 2023 Southern Book Prize winner. It is one helluva book, the kind of novel that requires the reader to think about the world they live in. This author's words stirred up all sorts of questions in me, and I couldn’t wait to ask him about them.

Before we talk about the book, I’d like you to describe it for anyone who is unlucky enough not to have read it.

“Lark Ascending” is set about twenty years in the future. It focuses on an Appalachian family on the run from a climate change catastrophe that has fueled an insurrection. The country has been taken over by Christian nationalists, and everybody’s been pushed northeast. They eventually board a crowded boat to find refuge in Ireland, a place of sanctuary. But once they get to Ireland, Lark is the only survivor of that boat. He goes on a journey — a long walk across Ireland with a dog and a mysterious woman, both of whom are in deep grief just as he is, and they're aiming for a place that is rumored to be a safe haven.

To me, the book is about the experience of deep grief. It's a meditation on Ireland, on the connection between people and dogs, on community, on created family.

As somebody who grew up in Maine, I was particularly interested to see that Maine makes an appearance. Lark and his family first find refuge there in the northern Appalachian Mountains, in the Bigelow Range. What made you choose Maine?

It's mostly logistical because, when I started writing the book, Australia was burning. Some studies say that one billion animals died in those fires. I was looking at different climate change projections and the one I latched onto was the forest fire projection. In that, the [United States] would be pushed northeast, so by the time we were in the main action of the novel, it makes sense they are already in the northeast.

You also brought in overlooked parts of the Appalachian South. For instance, Lark and his family are from western Maryland. We don't often talk about western Maryland as part of Appalachia.

I think western Maryland is so incredibly beautiful. A lot of it has been able to retain its beauty because not as much coal mining has happened in that area — very little. So, for me, it was sort of an Edenic part of Appalachia. It's just more pristine in that little area there on the Maryland-West Virginia border.

And I did want [Lark’s family] to be an Appalachian family. For one thing, when you're reading Appalachian literature, you don't often encounter academics and doctors. So, in this book, [Lark’s] father's a physician, his mother's a horticulturist, but, at the same time, they're Appalachian. They’re people who have been raised to know how to preserve their food and how to grow food. They've hiked the Appalachian Trail.

When I'm writing a book, even if it's set in Ireland, it still feels most comfortable for the point-of-view to be Appalachian. Lark is an Appalachian person in Ireland. He's seeing it through that lens.

"With 'Lark Ascending' House reveals himself to be an oracle from the future who has come back to illuminate our lived moment...The vision is terrifying and spare, but in House’s capable and delicate telling, it is also beautiful and compelling."

Wiley Cash,

New York Times bestselling author

(Every purchase helps keep our Appalachian magazine alive and thriving.)

I can see how your appreciation for Appalachia comes through in your writing about Ireland. I want to read a little piece of your book, written from Seamus the dog’s perspective:

Seamus dreams of the island when he sleeps. He dreams of chasing the gulls. In his dreams there is the sound of the sea — the endless, relentless, eternal crashing of the waves upon the black rocks, the smooth kiss of the water on the sandy beach. He dreams of the clicks and crunch of driftwood between his teeth. He sees the cows eying him with suspicion, the low moos they cooed to him on cool mornings when the air was so damp that he could see the tiny droplets like rain in front of his eyes. He pictures the man reaching down to scratch his head. In his sleep, he can feel this, the joy of it, the comfort.

That misty rain, those droplets felt very Appalachian to me, but this excerpt is about a dream — it’s about dog dream, but it's about a dream. I'm curious to know if dreams influence your writing.

Unfortunately, my dreams have always tended to be nightmares. I've always had a really active nightmare life. Sometimes people will talk about how they dream something for their book. I've never done that. However, a lot of my process is daydreaming, wakeful dreams.

While I was writing this book, I would go for a walk in the woods and put myself in Lark’s mind. I would not only see the forest as somebody walking through the forest, but I would think about it from the point of view of this deep grief he was in — losing the love of his life, losing his parents.

Sometimes I would look down at my beagle Ari and think about the moment Lark and Seamus started to walk together. What does [Lark] know? What’s he thinking? What's he observing about the dog?

I guess people think of that as imagination, but I feel more like it's daydreaming. It's such a blissful state because there's some disassociation from the rest of the world, the troubles of the world. There's this act of creation happening, so it's a meditative, lovely time for me. It's the best part of writing.

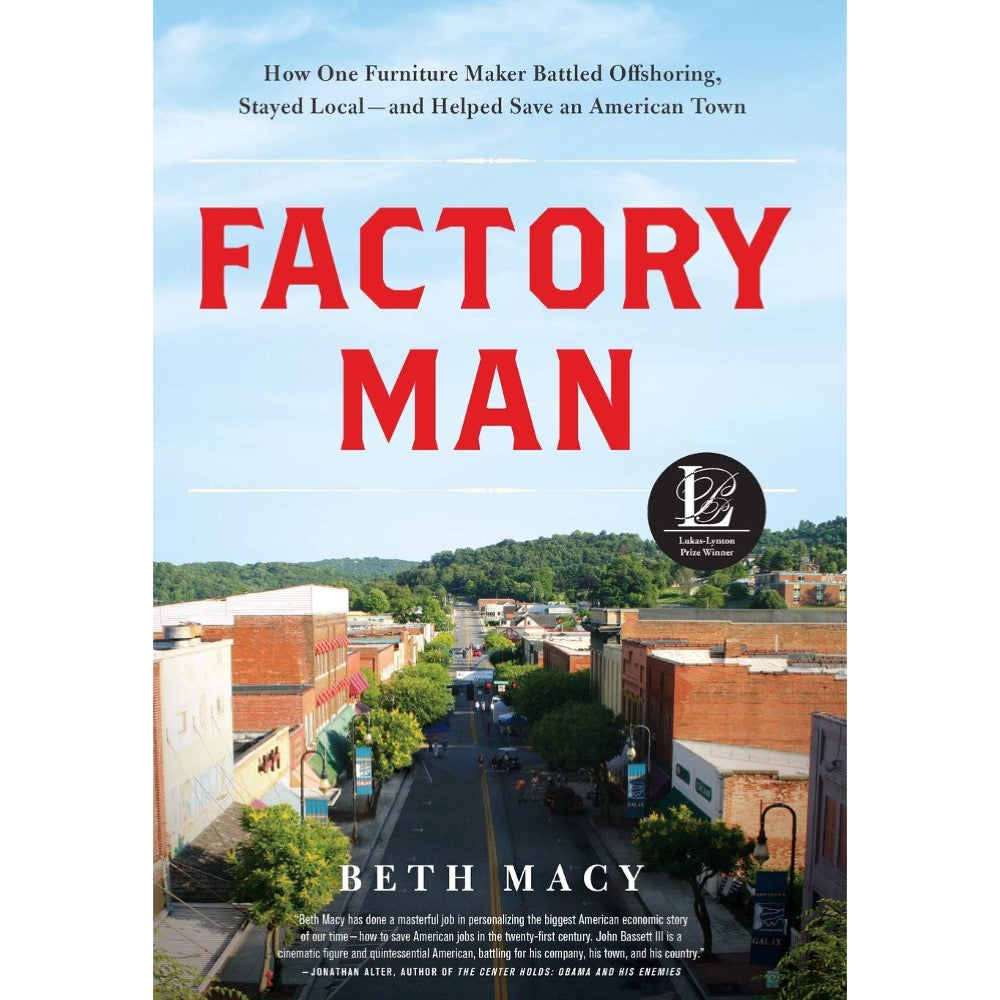

MORE AMAZING APPALACHIAN LIT

You mentioned grief. There's a line in the book where Lark says:

Only days before, we had been a family of six, and now we were only three. Every time I wretched over the side of the boat, I felt like I was vomiting up some of that grief. But nothing can get that out of you, no matter how hard you try.

My sense is that we can't write about things we haven't experienced—and grief is notable because it’s both an emotion and a state of being. What makes you able to write about grief in such a true way?

I started this book because I lost my aunt, who I just adored. She was like a third parent to me, and I was frozen after she died. For the first time since I was a teenager, I couldn't write. And so, I thought, “I'll just write about what I'm going through.”

I started writing about this man — a younger man than me — and a dog, walking across Ireland. I put them both in deep grief. And then I incorporated Helen, who’s also in deep grief.

They're in deep grief because they've lost somebody, but they're also in deep grief because they've lost their countries. Seamus’s whole country is that little island. That's all he knows. That's his whole world. Lark has lost his country to the fundamentalists. Helen has lost her country to the different factions that have taken over in the wake of all the upheaval.

I was drawing on not only the grief of losing my aunt but also the grief of feeling like I was losing my country. I still feel that way, but it felt much thicker at the very beginning. I started this book in 2016, and to see such bigotry given such a big platform was mind-blowing. So I was writing about two parallel griefs. I think one of them is a personal grief and the other is a collective grief — because you're feeling it with lots of other people.

“Lark Ascending” feels very predictive in that way. Not that you're setting yourself up as some sort of literary Nostradamus, but it feels like you're telling a story that shows the reader a future world and asks: “Is this what we want?”

Well, the book is about my greatest fears, but it's also about me trying to find hope. They're saying if we don't change something climate-wise, it's gonna be catastrophic in our lifetimes. We don't have politicians who are gonna change a damn thing. I think we have to accept that and think: “How are we going to get through this?”

I don't mean that in a cynical way. I mean it in an optimistic way. We can face catastrophe and retain our humanity.

In the book, I get into that through Ronan, the girl who's led on a leash by her father. To me, she is Lark’s opposite. Lark has been raised to survive through positive methods: foraging, farming, agrarianism, trying to do the least harm that he can. [Ronan] has been raised to be ruthless and to take whatever she needs. It doesn't mean she's evil and he's great. It just means we have a choice to make in how to approach catastrophe.

This interview has been condensed and edited.