ART FROM THE Cover of “the caretaker.”

“...he’d heard all manner of stories about what awaited him in Korea. Much of it was horsecrap: the NK ate rats and snakes raw, could see in the dark like cats. But some stories were true, including how…they’d come across and kill only one man when they might have killed three or four. They were leaving a message: We’re saving you for next time.”

— excerpt from “The Caretaker”

Ron Rash doesn’t rush.

Back when I was his student at Western Carolina University, I remember the acclaimed Appalachian novelist announcing he’d spent all day crafting a single sentence. Every word must matter, he explained to the class. Every word must cut to the marrow of the story.

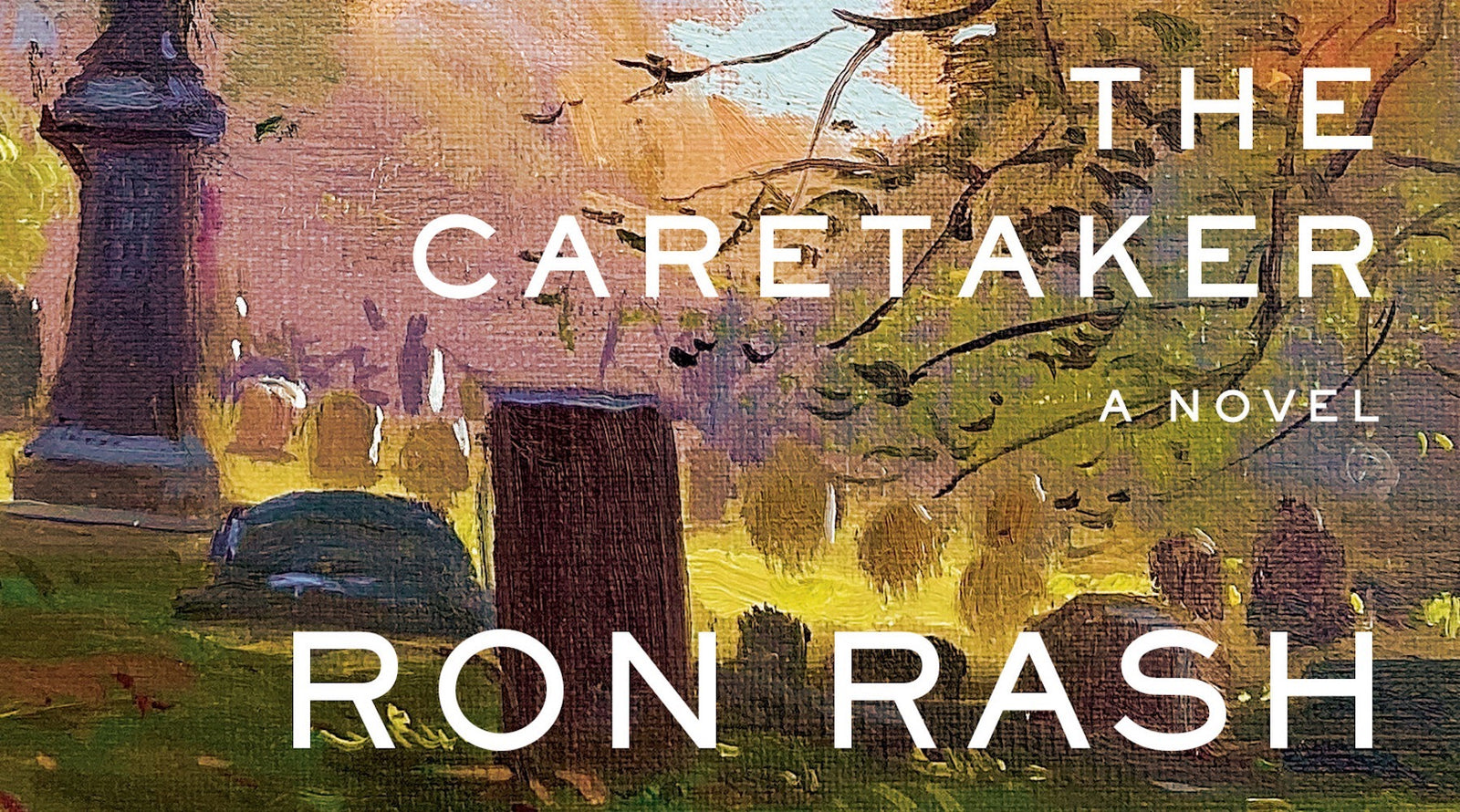

At the time, I figured him a little wacky to mull over one line for eight hours. But western North Carolina’s literary son — the author of New York Times Bestsellers such as “Serena” and searing short-story anthologies like “Something Rich and Strange” — proves his mettle with his newest novel, “The Caretaker.”

According to Ron, this story has been 30 years in the making. “I just couldn’t get it right,” he told me earlier this month, his honey-sweet drawl crackling on the other end. “I probably wrote about 1,000 pages because I continued making wrong turns and giving up. But then something would draw me back.”

After more than two decades of wordsmithing, Ron has landed on what may be his best book yet.

Officially hitting shelves today, the novel tells the breathless tale of Jacob Hampton, a young man from a well-to-do family whose elopement to penniless hotel maid Naomi Clarke angers his parents to the point of disownment. When Jacob is conscripted to leave the tiny town of Blowing Rock, North Carolina, and serve in the Korean War, he calls on Blackburn Gant, a cemetery caretaker shunned for his physical appearance, to help care for his pregnant wife.

What happens next is a “profound examination of friendship and rivalry as well as a riveting story of unfolding deceit.” Or so reads the book jacket. All I know is it’s a damn good read. And though Ron is too humble to say so himself, I think he’d agree.

In the interview below, the writer talks headstones, childhood trauma, and what’s next for his career.

Can you tell me more about where the inspiration for this story came from?

About 30 years ago, I heard about a woman who had been killed by her in-laws. Her husband was serving overseas, and the family didn’t approve of them being together. That story sat with me for a while. Since then, I’ve always wanted to explore the idea of how far parents will go in justifying their wrongs as acts of love.But that little piece of plot was just my stepping-off point. It’s hard to say where the rest of the story came from. The more I write, the more mysterious the process becomes.

When I took your class, you focused heavily on imbuing stories with a strong sense of place. What significance did the setting in “The Caretaker” have in moving your writing forward?

I’ve always wanted to set a novel on my grandparents’ farm. It’s situated right on the Blue Ridge Parkway between Blowing Rock and Boone in a little community called Aho. That place was hugely important to me. Though I grew up in Boiling Springs, I spent a lot of my summers on that farm. There was no television or vehicle. I would just fish and wander. It was more home than home. But here’s the eerie part. There was a cemetery right above the farm, with only a barbed wire fence dividing it and the cow pasture. I was never really frightened by the cemetery — many of my relatives were buried there — so I spent a lot of time wandering among the headstones. Looking back now, I guess that’s kind of a creepy thing for a kid to do. One day, though, I noticed a gravestone in there with just the word “Story.” That’s a last name up in those parts, but it’s normally spelled S-T-O-R-I-E. So, the image of that headstone stuck with me. I don’t want to say it was mystical, but I do think it inspired the character of Blackburn Gant.

The cemetery near your family’s farm obviously provided fodder. But what inspired you to build Blackburn’s character around a physical deformity that prompts such severe ostracism?

I suspect that all writers tend to be outsiders. They’re usually a little goofy, perhaps a bit dreamy. You definitely don’t feel like you’re part of the herd. But I’ll add something else to that: I had a speech impediment when I was four or five years old and had to deal with a good bit of taunting. It was tough. When you have that happen to you when you’re so young, you don’t forget it. You don’t forget what it feels like to be on the outside. In many ways, though, I’m glad it happened. I think it made me a more empathetic writer.

Besides ostracism, another recurring theme in the book is familial conflict. Actually, you explore this theme in many of your books, including “Saints at the River” and “The World Made Straight.” Why write about fractured families?

Tolstoy has this great quote about how happy families are not interesting. But I think more than that, I want to write about matters that relate to people’s lives. I suspect most of us understand the complexities of love within a family — how sometimes self-interest can be disguised as love. That kind of family conflict is interesting because so many of us have been through it, even those with good families. Misunderstandings are inevitable when you spend so much of your life crammed in a home together.

APPALACHIAN LIT

Family drama definitely makes for good books — good movies, too! I have to ask: Do you think “The Caretaker” will ever be turned into a film like “Serena” and “The World Made Straight”?

I never think about my novels being turned into movies. But I would probably make a lot more money if I did!

Whether destined for the big screens or not, I feel like “The Caretaker” definitely imparts some moral wisdom. Can you talk a bit more about what you hope readers learn from the book?

I hope that the reader perceives every character with a degree of ambiguity. These are not black-and-white characters. Not a single one is purely good or purely evil. Even Blackburn, who embodies everything I admire in human beings, isn’t perfect. He has his moments of jealousy. But I want to remind readers that people are pretty decent, all things aside. With the country being so divided these past few years, it’s easy to forget that.

Why did you feel so compelled to remind people of the good in the world?

I’ll be turning 70 this month, and I think when writers get to a particular stage in their career, they want to write a novel that is hopeful. They want to leave something behind they can feel good about.

What’s next for you? Is there another novel in the pipeline?

I’ve sworn I'll never write another novel probably after every novel I’ve written, but I just keep forgetting. So, who knows what’s next. For right now, I’m probably most interested in writing some short stories.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

AWARD-WINNING AUTHOR RON RASH

A PASSAGE FROM "THE CARETAKER"

Jacob was on guard duty, posted beside a river that separated the two armies. The night was colder than any he’d experienced back in Watauga County. This cold did more than seep into his skin. It encased fingers and feet in iron, made teeth rattle like glass about to break. No layering of wool and cotton beneath the pile-lined parka allayed it. For weeks Jacob had kept waiting for the cold to lift. Now it was March, but this place observed no calendar. The river was still frozen. Jacob envisioned ice all the way to the bottom—no current, fish stalled as if mounted. The river had a name but Jacob didn’t allow it to lodge in his memory. Since stepping onto the pier in Pusan, his goal had been to forget, not remember.

At Fort Polk he’d heard all manner of stories about what awaited him in Korea. Much of it was horsecrap: the NK ate rats and snakes raw, could see in the dark like cats. But some stories were true, including how they would crawl into an outpost, slit a soldier’s throat, then recede into the night. Even if you were on the opposite side of a river, they’d come across and kill only one man when they might have killed three or four. They were leaving a message: We’re saving you for next time.

Though the river was frozen, Jacob knew that didn’t matter. Two nights earlier, a North Korean had decapitated another unit’s sentry. Crawled over the ice to do it. Jacob scanned the flat, soundless snowscape before him. At least the moon was full tonight. A hunter’s moon, they called it back home. It silvered the crystals atop the river. If not wary of an enemy’s knife, Jacob would have taken time to marvel at such shimmering beauty. But even this small moment must be blocked. Jacob wanted Korea to be a house entered and then left, the door locked forever. He just had to survive. Twelve days ago, for the first time, his unit had been in a fight. Aubert, a Cajun from Louisiana, had been shot in the leg. The bullet shattered his kneecap, and the medic said he’d need a cane the rest of his life. That was fine, Aubert answered. He’d get home alive to his wife and children, and finally be warm.

Getting home was what mattered. According to Naomi’s last letter, Dr. Egan said the baby would come in May. That thought was the talisman Jacob carried with him. He could not die. God or fate, something, destined him and Naomi to have a life together. How else to explain that evening twenty months ago in Blowing Rock. At the exact moment he passed the Yonahlossee Theater, Naomi, a complete stranger, had been standing beside the ticket booth, coin in hand. If he’d looked up at the marquee, or if a friend had called from farther up the sidewalk, Jacob would never have noticed her.

She’d worn no earrings or bobby socks, no bright bows or bracelets like the other girls he knew. But such adornment would only distract from her face, the smooth skin and high cheekbones, striking blue eyes and long black hair. Love at first sight. But her prettiness was only part of what had held him there. As others went inside, Naomi rubbed a dime between her index finger and thumb, looking at the poster and then at the dime as people walked past her without a worry about the price.

So much in that instant was set into motion, including a shared life that ensured Jacob’s safe return. Even Naomi being in Blowing Rock that July evening was little short of miraculous, Naomi’s brother-in-law just happening to buy a copy of The Nashville Tennessean and noticing the ad: Seasonal Hotel Maids Needed. The Green Park Inn. Blowing Rock, North Carolina. Hadn’t that been fate too? Many soldiers brought something from home to help protect themselves, a rabbit’s foot, a lucky coin, a playing card, so why not a belief? Yet last week Doughtery, despite two crucifixes and a matchbox filled with four-leaf clovers, had stepped on a mine and been killed. So Jacob’s eyes did not leave the frozen river, his ears listening for the rub of cloth on ice, a scrape of fingernails.

Excerpted from “The Caretaker” by Ron Rash, published by Doubleday, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2023 by Ron Rash.